Poll: Should Preservation Review be Citywide or Continue Ward-by-Ward?

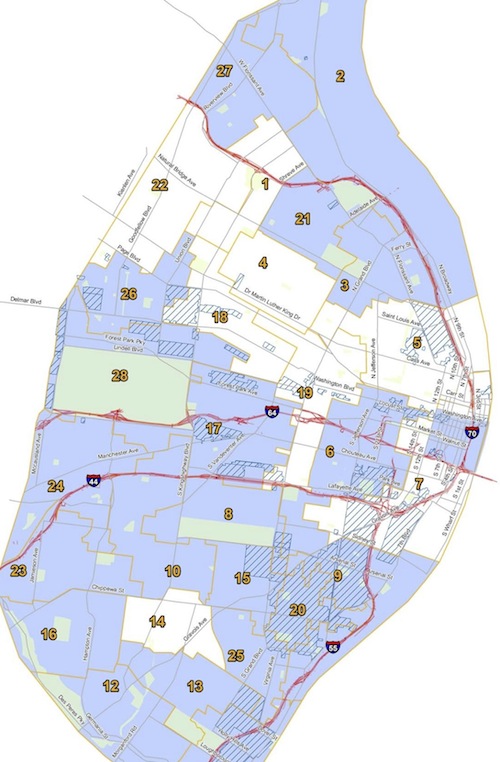

The city of St. Louis is divided into 28 wards and each alderman has authority over his/her ward, the city as a whole be damned.

As the above map show, eight of the twenty-eight wards are excluded from the city’s other  Preservation Review Districts:

Any demolition application in a Preservation Review District will be referred by the Building Division to the Cultural Resources Office for review. No demolition permit may be issued without the approval of the Office.

Criteria for Review:

The Office will consider these criteria in making its determination:

- redevelopment plans passed by ordinance;

- the building’s architectural quality;

- its structural condition;

- the demolition’s effect on its neighborhood;

- the building’s potential for reuse;

- urban design factors;

- any proposed subsequent construction;

- any commonly-controlled property.

So in 30% of the city buildings can be razed without any review by the staff hired to protect our cultural history. There are some exceptions, such as the 7th ward. It appears the CBD does have preservation review and other parts of the ward would be reviewed as part of of a National Register historic district. The same thing occurs in parts of the other seven non-review wards. Forget Team Four, lack of preservation review in six north side wards has done great damage.

But ward boundaries change this year due to redistricting. Preservation Review districts don’t automatically change, these must also be changed with new legislation. Â That is, unless it was simplified and covered the entire city. Here is an example of the description of one of twenty districts:

PRESERVATION REVIEW DISTRICT THIRTEEN

Beginning at the intersection of the centerlines of Kingshighwayand Lindell, and proceeding in a generally clockwise direction east along the centerlines to Taylor, north to Maryland, east to Boyle, south to West Pine, east to Sarah, south to Laclede, east to Spring, south to Market, east to Grand, north to the Forest Park Parkway, east to Compton, south to Chouteau, west to Grand, south to Park, west to 39th, south to Blaine, west to Tower Grove, south to Interstate 44, west to Kingshighway, north to the St. Louis & San Francisco Railway tracks, west to Hampton, north to Manchester, west to Graham, north to Oakland, east to the southern prolongation of Euclid, north to Barnes Hospital Plaza, west to Kingshighway, and north to the point of beginning. (source)

Think of all the staff time to write new legislation, to alter the city’s property database.

My loft will go from being in the 6th ward to the 5th ward, from preservation review to non-review. The buildings above, in the block to the west of me, Â will also go from 6th to 5th, will suddenly be at greater risk of being razed without public input once the preservation review districts are revised. The substation is on Landmark’s 2010 Most Endangered List.

All this is to introduce the poll question for this week:Â Should Preservation Review be Citywide or Continue Ward-by-Ward? Â The poll is located in the upper right corner of the blog.

– Steve Patterson

I vote no. One, no city remains frozen in time – change happens. Two, tastes change – old does not necessarily equal better than new, and neither bureaucrats nor a tiny group of citizen advocates are or should be the arbiters of any cty’s design standards. Three, unless the government is going to pay to preserve vacant buildings, they shouldn’t expect private owners to do so – unfunded mandates are just shifting responsibilities. Four, too many restrictions drive away investment and business. Five, many of our challenges come from valid and invalid perceptions about crime and schools, which reduces demand and increases supply. Six, a city of 325,000 simply doesn’t need as many structures as a city of 850,000. And seven, even if you say no today, if an owner really wants a building gone, it will eventually disappear.

Once a building is damaged “beyond repair”, from fire or water damage, it will need to be demolished to protect the public. We have way too many examples of vacant and deteriorating buildings that should be demolished tomorrow. These passive-aggressive owners (including the city’s LRA) do more to create an appearance of true blight that scares away both residents and businesses (and the very reason to save old buildings). “The vacant transit substation & Dragon Trading buildings” are at risk of demolition simply because they don’t have users willing or able to spend the significant dollars to put them to viable contemporary uses.

The real question is should we be a ghost city, one full of stately-but-empty buildings, or should we focus on moving forward, doing whatever is necessary to attract and keep private investment? A vacant building doesn’t look too bad for its first ten or twenty years, but after 30, 40 or 50 years of benigh neglect, it’s going to take a significant investment, if you can even find someone willing to make the it, to bring it back to a real use. Do Fenton and Hazelwood actually have the better idea? Concede that things change, knock things down and start over?

I vote no. One, no city remains frozen in time – change happens. Two, tastes change – old does not necessarily equal better than new, and neither bureaucrats nor a tiny group of citizen advocates are or should be the arbiters of any cty’s design standards. Three, unless the government is going to pay to preserve vacant buildings, they shouldn’t expect private owners to do so – unfunded mandates are just shifting responsibilities. Four, too many restrictions drive away investment and business. Five, many of our challenges come from valid and invalid perceptions about crime and schools, which reduces demand and increases supply. Six, a city of 325,000 simply doesn’t need as many structures as a city of 850,000. And seven, even if you say no today, if an owner really wants a building gone, it will eventually disappear.

Once a building is damaged “beyond repair”, from fire or water damage, it will need to be demolished to protect the public. We have way too many examples of vacant and deteriorating buildings that should be demolished tomorrow. These passive-aggressive owners (including the city’s LRA) do more to create an appearance of true blight that scares away both residents and businesses (and the very reason to save old buildings). “The vacant transit substation & Dragon Trading buildings” are at risk of demolition simply because they don’t have users willing or able to spend the significant dollars to put them to viable contemporary uses.

The real question is should we be a ghost city, one full of stately-but-empty buildings, or should we focus on moving forward, doing whatever is necessary to attract and keep private investment? A vacant building doesn’t look too bad for its first ten or twenty years, but after 30, 40 or 50 years of benigh neglect, it’s going to take a significant investment, if you can even find someone willing to make the it, to bring it back to a real use. Do Fenton and Hazelwood actually have the better idea? Concede that things change, knock things down and start over?

Preservation Review simply adds a review step to ensure we don’t raze something of cultural value. City staff can, and do, approve demolition permits.

Couldn’t disagree with you more.

Preservation Review simply adds a review step to ensure we don’t raze something of cultural value. City staff can, and do, approve demolition permits.

Couldn’t disagree with you more.

Preservation review should be city wide of course. Beyond buildings of historical and cultural significance, buildings also create density, transit friendly orientations, neighborhood texture and much more. There is many reasons to review every building to be demolished. I have been a participant in bringing some buildings in very serious condition up to current standards, so the idea of a brick wall being down is not necessarily a reason to demo the building. I can also point to the many buildings rehabbed in Old North, Sean Thomas and Old North have brought many buildings back from the dead.

Anything goes capitalism has not worked and it will not work in the future.

A building is not like a frying pan to discard when tired of, it is a community asset. I’m sorry capitalists can’t run rampant over everything they see in pursuit of profit (real or imagined). The truth is we are a community, with the values and goals of a community.

Free for all capitalism has not only failed in St. Louis, but the nation as well. If free for all capitalism worked America and St. Louis would be prospering. It is not happening.

Convince me free for all capitalism is the right way to go, I’m all ears, I’m listening. If someone wants to demolish a building then let us hear their alternatives.

Our current corporate overlords are very happy to demo everything in sight to maintain the grip of oil and their subsidiaries.

The reason St Louis is losing population is the continuation of oil friendly policies, the policy that emphasis demo rather than a rebirth that makes the city transit friendly as an alternative.

I know there will be no answers, as usual.

Â

Preservation review should be city wide of course. Beyond buildings of historical and cultural significance, buildings also create density, transit friendly orientations, neighborhood texture and much more. There is many reasons to review every building to be demolished. I have been a participant in bringing some buildings in very serious condition up to current standards, so the idea of a brick wall being down is not necessarily a reason to demo the building. I can also point to the many buildings rehabbed in Old North, Sean Thomas and Old North have brought many buildings back from the dead.

Anything goes capitalism has not worked and it will not work in the future.

A building is not like a frying pan to discard when tired of, it is a community asset. I’m sorry capitalists can’t run rampant over everything they see in pursuit of profit (real or imagined). The truth is we are a community, with the values and goals of a community.

Free for all capitalism has not only failed in St. Louis, but the nation as well. If free for all capitalism worked America and St. Louis would be prospering. It is not happening.

Convince me free for all capitalism is the right way to go, I’m all ears, I’m listening. If someone wants to demolish a building then let us hear their alternatives.

Our current corporate overlords are very happy to demo everything in sight to maintain the grip of oil and their subsidiaries.

The reason St Louis is losing population is the continuation of oil friendly policies, the policy that emphasis demo rather than a rebirth that makes the city transit friendly as an alternative.

I know there will be no answers, as usual.

Upon further consideration, there seems to be three kinds of demolition. One, there’s demolition that (needs to) happens when a building is already falling down, when it’s an out-and-out safety hazard. Two, there’s anticipatory / optomistic demolitions, where an institution or a developer is assembling a larger parcel out of multiple smaller ones. And three, there’s demolition that occurs as a part of a direct replacement / redevelopment. I’d argue that the first and third kinds are less objectionable than the second kind.

With the first kind, it’s hard to argue safety. The real issue is why it got that bad in the first place? Fires, explosions, floods, tornadoes, sinkholes and earthquakes all happen, and most owners don’t want them to, but the building still needs to come down. Outright neglect / lack of maintenance comes either from no money or an intent to destroy the building, albeit slowly. These are the passive-aggressive owners I’m talking about, the ones who will either do things “their way”, in spite of any government regulations or simply because they see no future financial returns.

With the third kind, we can argue about the architectural and urban design details, but at least something is going back in within months, maintaining density and supporting the economy. This is the kind that most aldermen will support, and is the kind that is most likely to become “exempted” from preservation rules – money talks, for better or for worse.

The second kind is probably the most problematic, for all of us. Servicable buildings are torn down, but nothing replaces them for years or decades. Parts of the city ARE scarred because of this, and the barrenness, instead of being an incentive, becomes a deterrent. And this gets back to your (and my) concerns about addressing the underlying issues that scare too many people (and their dollars) out of the urban environment – every empty building is at risk, occupied ones, not so much.

Central West End. Lafayette Square. Soulard. Benton Park. All were once targeted for demolition in the name of highly specious “progress”. The real question is why the argument about historic preservation is one that St. Louis has to have with itself over and over again. If bureaucrats do not always know best, neither did the “smart money” individuals in the ’50s whose visionary solution was to bulldoze old “obsolete” neighborhoods and replace them with ranch houses on cul de sacs. Mass demolition was not progress then and it is certainly not today.

Central West End. Lafayette Square. Soulard. Benton Park. All were once targeted for demolition in the name of highly specious “progress”. The real question is why the argument about historic preservation is one that St. Louis has to have with itself over and over again. If bureaucrats do not always know best, neither did the “smart money” individuals in the ’50s whose visionary solution was to bulldoze old “obsolete” neighborhoods and replace them with ranch houses on cul de sacs. Mass demolition was not progress then and it is certainly not today.

Today’s demolition is worse, a building by building assault on the fabric of the city. We have fight the same battle over and over.

My response to gmichaud covers most of it, but the most pernicious “assualt on the urban fabric” comes from demoltion done for surface parking lots. Unfortunately, our property values have fallen to the point (in most of the city) that the value of maintaining the structure, any structure, is less than the value of providing more off-street parking. I doubt that there’s the political will to prohibit demolition for this, but there may be some “middle ground” where facades are forced to be preserved, even if surface parking is the only thing happening behind them.

So, Pruitt-Igoe should have been saved? The Chrysler plant in Fenton?

What happened with Pruitt-Igoe was tragic in its own way and can be traced back to the basic design of the project. This deeply flawed development was itself an expression of the “clear it all and start over new” mentality of the post-WW II era. I would have been more interested in seeing some of the historic structures that were probably blown up to permit the “progress” of P-I saved and reused instead.

The neighborhood that was razed was largely Irish, poor & rough to be sure. Most of the buildings were likely highly ordinary. As you know, it is the run-of-the-mill buildings that comprise most of this city.

I think you would agree that individually “run of the mill” buildings, especially when assembled in an intact concentration called a neighborhood, have historical value and interest.

I do agree. But how do we integrate “historical value and interest” with private property rights and the need to stay relevent? You stated that “What happened with Pruitt-Igoe was tragic in its own way and can be traced back to the basic design of the project.” I agree. But, by extension, if a 1920’s-vintage neighborhood is being redeveloped, who’s to say that its transformation can’t also “be traced back to the basic design of the” area? Times change. Needs change. What worked well 50 years ago may not work well today. Who gets to be the decider? And do 1950’s-vintage buildings have less value than 1920’s-vintage ones?

THE fundamental change of the 20th Century was the perfection of either the automobile or the internal-combustion engine. In 1911, if you wanted to go somewhere in St. Louis, you walked or you rode on an electric streetcar (which you first had to walk to). In 2011, you drive yourself or ride in a vehicle that isn’t tethered to a wire. (Yes, we have Metro and bicycles, but they make up less than 1% of all our trips.) The physical changes required to accomodate all our private vehicles define our built environment today. You may not like it, but it is our reality. How we accomodate this paradigm shift is the challenge. And just saying “no” isn’t the answer, either, since our expanded mobility gives us multiple other answers and choices.

One big knock against St. Louis is “how hard it is to do business in the city”. Outside of defined historic districts, adding “a review step to ensure we don’t raze something of cultural value” may sound benign, even well-intentioned, but it’s also a symptom of excessive government control.

I’m not sure what you mean by “the need to stay relevant”. One way for the city to become increasingly irrelevant is for it to continually erode its most distinctive characteristic, historic architecture, and replace it with generic architectural Kleenexes and ugly-ass parking garages that could be in Atlanta, Phoenix, Boise, or Charlotte. Or anywhere. And nowhere. St. Louisans should take greater stock of the fact that transplants from other places, notably those from “hot” cities all over the country, might sometimes be unkind in their assessments of our town, though many note the architecture. It’s a distinctly consistent plus. A neighbor originally from NYC recently answered my question about what she thought of life in St. Louis by saying, after a thoughtful pause, “I love the architecture.”

So-called “private property rights” are already curtailed in ways that have nothing to do with historic preservation. One’s ownership of a certain property does not trump all expectations of the surrounding community, comprised of individuals who share the neighborhood and are themselves also bound by laws and ordinances intended to serve a larger public interest. My ownership of a house does not give me the right to open a martini cabaret in my dining room with jazz trios holding forth on the front porch; I have a garage, but I cannot open a car-repair outfit in it because I own it. My right to free speech does not entitle me to slander or libel people I may not like or to call them on the phone and threaten them. Laws rightfully include perceived societal betterment and interest.

Sometimes demolition is unavoidable. Too often, and especially when it becomes a matter of “common sense” policy, the entire community is diminished, literally and otherwise, by demolition of its fabric, irrespective of who owns the squandered bricks and stones in question.

A city that loses half of its population and more than half of its jobs over 50 years needs to take hard look in the mirror. When people look at the region, the city is apparently the first choice for fewer and fewer of them – it’s becoming less and less relevent. And I do agree that there’s too much abandonment and demolition going on – I like the architecture and the urban fabric, it’s why I live in and care abiut the city. Where we disagree is on how to minimize the cancer. I see the problem as an economic one – if the buildings were worth more, they wouldn’t be being neglected, abandoned or torn down. Fix the problems that are driving people out of the city – crime, schools, racism, taxes – and property values will increase. We get surface parking and vacant lots because that’s the current “highest and best use” based on what people are willing to pay, period. Just say no (to demolition) is, at best, a band-aid – we need to find productive uses for these structures to really save them.

Today’s demolition is worse, a building by building assault on the fabric of the city. We have fight the same battle over and over.

Upon further consideration, there seems to be three kinds of demolition. One, there’s demolition that (needs to) happens when a building is already falling down, when it’s an out-and-out safety hazard. Two, there’s anticipatory / optomistic demolitions, where an institution or a developer is assembling a larger parcel out of multiple smaller ones. And three, there’s demolition that occurs as a part of a direct replacement / redevelopment. I’d argue that the first and third kinds are less objectionable than the second kind.

With the first kind, it’s hard to argue safety. The real issue is why it got that bad in the first place? Fires, explosions, floods, tornadoes, sinkholes and earthquakes all happen, and most owners don’t want them to, but the building still needs to come down. Outright neglect / lack of maintenance comes either from no money or an intent to destroy the building, albeit slowly. These are the passive-aggressive owners I’m talking about, the ones who will either do things “their way”, in spite of any government regulations or simply because they see no future financial returns.

With the third kind, we can argue about the architectural and urban design details, but at least something is going back in within months, maintaining density and supporting the economy. This is the kind that most aldermen will support, and is the kind that is most likely to become “exempted” from preservation rules – money talks, for better or for worse.

The second kind is probably the most problematic, for all of us. Servicable buildings are torn down, but nothing replaces them for years or decades. Parts of the city ARE scarred because of this, and the barrenness, instead of being an incentive, becomes a deterrent. And this gets back to your (and my) concerns about addressing the underlying issues that scare too many people (and their dollars) out of the urban environment – every empty building is at risk, occupied ones, not so much.

My response to gmichaud covers most of it, but the most pernicious “assualt on the urban fabric” comes from demoltion done for surface parking lots. Unfortunately, our property values have fallen to the point (in most of the city) that the value of maintaining the structure, any structure, is less than the value of providing more off-street parking. I doubt that there’s the political will to prohibit demolition for this, but there may be some “middle ground” where facades are forced to be preserved, even if surface parking is the only thing happening behind them.

So, Pruitt-Igoe should have been saved? The Chrysler plant in Fenton?

What happened with Pruitt-Igoe was tragic in its own way and can be traced back to the basic design of the project. This deeply flawed development was itself an expression of the “clear it all and start over new” mentality of the post-WW II era. I would have been more interested in seeing some of the historic structures that were probably blown up to permit the “progress” of P-I saved and reused instead. Â

The neighborhood that was razed was largely Irish, poor & rough to be sure. Most of the buildings were likely highly ordinary. As you know, it is the run-of-the-mill buildings that comprise most of this city.

I think you would agree that individually “run of the mill” buildings, especially when assembled in an intact concentration called a neighborhood, have historical value and interest. Â

I do agree. But how do we integrate “historical value and interest” with private property rights and the need to stay relevent? You stated that “What happened with Pruitt-Igoe was tragic in its own way and can be traced back to the basic design of the project.” I agree. But, by extension, if a 1920’s-vintage neighborhood is being redeveloped, who’s to say that its transformation can’t also “be traced back to the basic design of the” area? Times change. Needs change. What worked well 50 years ago may not work well today. Who gets to be the decider? And do 1950’s-vintage buildings have less value than 1920’s-vintage ones?

THE fundamental change of the 20th Century was the perfection of either the automobile or the internal-combustion engine. In 1911, if you wanted to go somewhere in St. Louis, you walked or you rode on an electric streetcar (which you first had to walk to). In 2011, you drive yourself or ride in a vehicle that isn’t tethered to a wire. (Yes, we have Metro and bicycles, but they make up less than 1% of all our trips.) The physical changes required to accomodate all our private vehicles define our built environment today. You may not like it, but it is our reality. How we accomodate this paradigm shift is the challenge. And just saying “no” isn’t the answer, either, since our expanded mobility gives us multiple other answers and choices.

One big knock against St. Louis is “how hard it is to do business in the city”. Outside of defined historic districts, adding “a review step to ensure we don’t raze something of cultural value” may sound benign, even well-intentioned, but it’s also a symptom of excessive government control.

Related, from Cincinnati:Â http://communitypress.cincinnati.com/article/AB/20110716/NEWS01/107170354/Thousands-historical-buildings-may-risk?odyssey=nav%7Chead

Related, from Cincinnati: http://communitypress.cincinnati.com/article/AB/20110716/NEWS01/107170354/Thousands-historical-buildings-may-risk?odyssey=nav%7Chead

I’m not sure what you mean by “the need to stay relevant”. One way for the city to become increasingly irrelevant is for it to continually erode its most distinctive characteristic, historic architecture, and replace it with generic architectural Kleenexes and ugly-ass parking garages that could be in Atlanta, Phoenix, Boise, or Charlotte. Or anywhere. And nowhere. St. Louisans should take greater stock of the fact that transplants from other places, notably those from “hot” cities all over the country, might sometimes be unkind in their assessments of our town, though many note the architecture. It’s a distinctly consistent plus. A neighbor originally from NYC recently answered my question about what she thought of life in St. Louis by saying, after a thoughtful pause, “I love the architecture.”

So-called “private property rights” are already curtailed in ways that have nothing to do with historic preservation. One’s ownership of a certain property does not trump all expectations of the surrounding community, comprised of individuals who share the neighborhood and are themselves also bound by laws and ordinances intended to serve a larger public interest. My ownership of a house does not give me the right to open a martini cabaret in my dining room with jazz trios holding forth on the front porch; I have a garage, but I cannot open a car-repair outfit in it because I own it. My right to free speech does not entitle me to slander or libel people I may not like or to call them on the phone and threaten them. Laws rightfully include perceived societal betterment and interest.

Sometimes demolition is unavoidable. Too often, and especially when it becomes a matter of “common sense” policy, the entire community is diminished, literally and otherwise, by demolition of its fabric, irrespective of who owns the squandered bricks and stones in question.   Â

A city that loses half of its population and more than half of its jobs over 50 years needs to take hard look in the mirror. When people look at the region, the city is apparently the first choice for fewer and fewer of them - it’s becoming less and less relevent. And I do agree that there’s too much abandonment and demolition going on – I like the architecture and the urban fabric, it’s why I live in and care abiut the city. Where we disagree is on how to minimize the cancer. I see the problem as an economic one – if the buildings were worth more, they wouldn’t be being neglected, abandoned or torn down. Fix the problems that are driving people out of the city – crime, schools, racism, taxes – and property values will increase. We get surface parking and vacant lots because that’s the current “highest and best use” based on what people are willing to pay, period. Just say no (to demolition) is, at best, a band-aid – we need to find productive uses for these structures to really save them.

A city that loses half of its population and more than half of its jobs over 50 years needs to take hard look in the mirror. When people look at the region, the city is apparently the first choice for fewer and fewer of them - it’s becoming less and less relevent. And I do agree that there’s too much abandonment and demolition going on – I like the architecture and the urban fabric, it’s why I live in and care abiut the city. Where we disagree is on how to minimize the cancer. I see the problem as an economic one – if the buildings were worth more, they wouldn’t be being neglected, abandoned or torn down. Fix the problems that are driving people out of the city – crime, schools, racism, taxes – and property values will increase. We get surface parking and vacant lots because that’s the current “highest and best use” based on what people are willing to pay, period. Just say no (to demolition) is, at best, a band-aid – we need to find productive uses for these structures to really save them.

There

should be a city wide urban design review, along with a preservation review.

Take

a good example: the circular triple AAA building on Lindell. It is proposed that a CVS

Pharmacy replace it. Where is the debate about the type of

corridor Lindell should become? The Catholic Church has a tremendous interest

in the building out of the corridor connecting the Catholic Basilica and

associated buildings with St. Louis U. and their student base. Grand Center is also

producing a plan that would benefit from an attractive Lindell corridor. In

fact it is a corridor that could run

from downtown to Washington U. It is in the public interest to understand and

support the direction of urban development.

Creating

a walking, transit friendly, including bicycles and other means, balanced with

the auto would require that CVS bring its façade along the street or near it. If

they build a massive parking lot as they have done at the corner of Grand and

Gravois, it would be unacceptable on Lindell and will degrade the walking and

transit environment in a serious way.

Developers

should understand that they come into St. Louis, there are design concerns to

be considered. Building is a public art that has many consequences concerning the

development of movement systems and quality of life issues, including the creation

of public space. Â Preservation, what to demo

and what to replace anew requires consideration of a clear understanding of

broader goals and whether the new solution will better meet the needs of citizens over

the long haul.

Only

then should a building be demolished.

Â

There

should be a city wide urban design review, along with a preservation review.

Take

a good example: the circular triple AAA building on Lindell. It is proposed that a CVS

Pharmacy replace it. Where is the debate about the type of

corridor Lindell should become? The Catholic Church has a tremendous interest

in the building out of the corridor connecting the Catholic Basilica and

associated buildings with St. Louis U. and their student base. Grand Center is also

producing a plan that would benefit from an attractive Lindell corridor. In

fact it is a corridor that could run

from downtown to Washington U. It is in the public interest to understand and

support the direction of urban development.

Creating

a walking, transit friendly, including bicycles and other means, balanced with

the auto would require that CVS bring its façade along the street or near it. If

they build a massive parking lot as they have done at the corner of Grand and

Gravois, it would be unacceptable on Lindell and will degrade the walking and

transit environment in a serious way.

Developers

should understand that they come into St. Louis, there are design concerns to

be considered. Building is a public art that has many consequences concerning the

development of movement systems and quality of life issues, including the creation

of public space. Preservation, what to demo

and what to replace anew requires consideration of a clear understanding of

broader goals and whether the new solution will better meet the needs of citizens over

the long haul.

Only

then should a building be demolished.

Here

is an analysis on the impact of preservation review and urban design review.

The

Triple AAA building echos’ the Basilica circular building up the street. That

alone creates

and unusual atmosphere which encourages new architectural

solutions, especially those that echo the circle.

Let’s

take Lindell from Kingshighway to Grand. The area near Kingshighway is filled

with large, medium rises that have a high density of people, (probably some of

the highest densities in St. Louis) on the Grand side there is the density of

St Louis U. students and Grand Center. Is it practical to develop a Euclid, the

loop, South grand, Cherokee style section that can be combined with new transit

options?

The

point is that concerns about design should be the debate, not whether CVS can

dump an acre of parking surrounding a building. (Check out Gravois and

Chippewa). Parking becomes a billboard or as Camilo Sitte says it is a “wedding

cake designâ€.

What

is the plan for a corridor on Lindell? Connections from Grand Center to Euclid

await. Creating a changed atmosphere on Lindell would not take many years. The new

3949 Lindell building is a perfect example of a building that should be in high

regard in attempting to relate to pedestrians, bicycles and transit.

CVS

has buildings, for instance in Harlem, that are purely urban, so they can do

the walk if the political establishment demands it from them.

Leadership,

both in the press and political arena, lack the courage to tackle American or

even problems in St. Louis. The real question is why there is no new thinking

in city planning? Especially in light of a world of less, more expensive oil

and potential climate change.

Irregardless,

the livability of the city is also at stake, should Lindell become a corridor

of transit and alternatives, or dedicated solely to the automobile? What

defines livability? If Lindell is successful how does this impact other city

routes?

Since

there are no corridor guidelines a transparent debate about the fate of Lindell

and the Triple A building should occur. Real leadership should recognize city aspirations.

I hardly think building a CVS parking lot with building stuck behind a sea of

parking spaces is the way to go.

New

standards need to established, the past way of doing business is still alive

and forced down everyone’s throats. It is not best for citizens or the future

for this to continue. The current way of doing business is clearly a failure

for the city.

More

development will be attracted with a coherent corridor plan, that is the irony,

Â

Here

is an analysis on the impact of preservation review and urban design review.

The

Triple AAA building echos’ the Basilica circular building up the street. That

alone creates

and unusual atmosphere which encourages new architectural

solutions, especially those that echo the circle.

Let’s

take Lindell from Kingshighway to Grand. The area near Kingshighway is filled

with large, medium rises that have a high density of people, (probably some of

the highest densities in St. Louis) on the Grand side there is the density of

St Louis U. students and Grand Center. Is it practical to develop a Euclid, the

loop, South grand, Cherokee style section that can be combined with new transit

options?

The

point is that concerns about design should be the debate, not whether CVS can

dump an acre of parking surrounding a building. (Check out Gravois and

Chippewa). Parking becomes a billboard or as Camilo Sitte says it is a “wedding

cake design”.

What

is the plan for a corridor on Lindell? Connections from Grand Center to Euclid

await. Creating a changed atmosphere on Lindell would not take many years. The new

3949 Lindell building is a perfect example of a building that should be in high

regard in attempting to relate to pedestrians, bicycles and transit.

CVS

has buildings, for instance in Harlem, that are purely urban, so they can do

the walk if the political establishment demands it from them.

Leadership,

both in the press and political arena, lack the courage to tackle American or

even problems in St. Louis. The real question is why there is no new thinking

in city planning? Especially in light of a world of less, more expensive oil

and potential climate change.

Irregardless,

the livability of the city is also at stake, should Lindell become a corridor

of transit and alternatives, or dedicated solely to the automobile? What

defines livability? If Lindell is successful how does this impact other city

routes?

Since

there are no corridor guidelines a transparent debate about the fate of Lindell

and the Triple A building should occur. Real leadership should recognize city aspirations.

I hardly think building a CVS parking lot with building stuck behind a sea of

parking spaces is the way to go.

New

standards need to established, the past way of doing business is still alive

and forced down everyone’s throats. It is not best for citizens or the future

for this to continue. The current way of doing business is clearly a failure

for the city.

More

development will be attracted with a coherent corridor plan, that is the irony,