Why Not Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Instead Of Modern Streetcar?

Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) has been used effectively in cities all over the world to improve public transit service, over previous bus service. With the proposed St. Louis Streetcar now going through the approval process some have suggested BRT as a less costly alternative. Seemed like a good reason to begin looking at the similarities and differences.

Similarities between BRT and modern streetcar:

- Fewer stops than standard bus service, but more often than light rail

- Faster on dedicated lanes, but can run in lanes stared with traffic

- Unique branding that is distinct from local bus service

- Higher capacities than bus service, though it varies depending upon the BRT vehicle

- Increased ridership and development over bus

Differences between BRT and modern streetcar:

- BRT can be re-routed, though stops are not changed easily. Streetcar routes unlikely to change due to capital costs.

- Tracks & wires convey the message of transit even when vehicle not present, BRT is easier to ignore.

- Many service enhancements are optional with BRT, thus BRT lite. These are not optional with streetcars.

- Streetcar vehicles have a significantly longer service life than BRT vehicles.

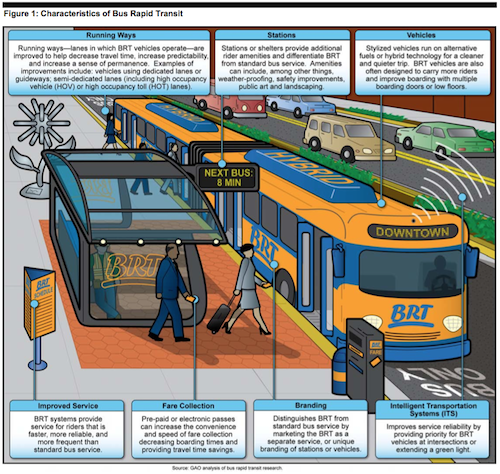

Few can even agree on what minimum combination of service enhancements are necessary to be called BRT, the US Government Accountability Office says, “BRT generally includes improvements to seven features–running ways, stations, vehicles, intelligent transportation systems, fare collection, branding, and service.”

Projects Improve Transit Service and Can Contribute to Economic Development” page 6, click to download PDF

Fare collection for standard buses is done as each passenger boards, whereas light rail systems use off-siteboard fare collection to reduce total boarding time. Modern streetcars, like light rail, tend to also use off-siteboard fare collection or on-board payment from one of several machines, allowing for faster boarding

Here’s a summary of what the GAO found out about BRT in the US:

U.S. bus rapid transit (BRT) projects we reviewed include features that distinguished BRT from standard bus service and improved riders’ experience. However, few of the projects (5 of 20) used dedicated or semi-dedicated lanes— a feature commonly associated with BRT and included in international systems to reduce travel time and attract riders. Project sponsors and planners explained that decisions on which features to incorporate into BRT projects were influenced by costs, community needs, and the ability to phase in additional features. For example, one project sponsor explained that well-lighted shelters with security cameras and real-time information displays were included to increase passengers’ sense of safety in the evening. Project sponsors told us they plan to incorporate additional features such as off-board fare collection over time.

The BRT projects we reviewed generally increased ridership and improved service over the previous transit service. Specifically, 13 of the 15 project sponsors that provided ridership data reported increases in ridership after 1 year of service and reduced average travel times of 10 to 35 percent over previous bus services. However, even with increases in ridership, U.S. BRT projects usually carry fewer total riders than rail transit projects and international BRT systems. Project sponsors and other stakeholders attribute this to higher population densities internationally and riders who prefer rail transit. However, some projects—such as the M15 BRT line in New York City—carry more than 55,000 riders per day.

Capital costs for BRT projects were generally lower than for rail transit projects and accounted for a small percent of the Federal Transit Administration’s (FTA) New, Small, and Very Small Starts’ funding although they accounted for over 50 percent of projects with grant agreements since fiscal year 2005. Project sponsors also told us that BRT projects can provide rail-like benefits at lower capital costs. However, differences in capital costs are due in part to elements needed for rail transit that are not required for BRT and can be considered in context of total riders, costs for operations, and other long-term costs such as vehicle replacement.

We found that although many factors contribute to economic development, most local officials we visited believe that BRT projects are contributing to localized economic development. For instance, officials in Cleveland told us that between $4 and $5 billion was invested near the Healthline BRT project—associated with major hospitals and universities in the corridor. Project sponsors in other cities told us that there is potential for development near BRT projects; however, development to date has been limited by broader economic conditions—most notably the recent recession. While most local officials believe that rail transit has a greater economic development potential than BRT, they agreed that certain factors can enhance BRT’s ability to contribute to economic development, including physical BRT features that relay a sense of permanence to developers; key employment and activity centers located along the corridor; and local policies and incentives that encourage transit-oriented development. Our analysis of land value changes near BRT lends support to these themes. In addition to economic development, BRT project sponsors highlighted other community benefits including quick construction and implementation and operational flexibility.

Here are more quotes from the same report:

Operating costs:

We also heard from stakeholders and project sponsors that operating costs for BRT and rail transit depend strongly on the density and ridership in the corridor. For example, according to one transit expert, while signaling and control costs are high for rail transit, there is a tipping point where given a high enough density and ridership, rail transit begins to have lower operating costs overall. (p31)

Land-Use:

BRT project sponsors and experts we spoke to told us that transit- supportive policies and development incentives can play a crucial role in helping to attract and spur economic development. Local officials in four of our five site-visit locations described policies and incentives that were designed (or are being developed) to attract development near BRT and other transit projects. For example, Los Angeles city officials told us that the city’s mayor recently created a transit-oriented development cabinet tasked with improving and maintaining coordination between Los Angeles Metro and city staff and developing policies and procedures in support of transit-oriented developments. They told us that the city is currently working on lifting requirements that require large amounts of parking and allow for only one- or two-story developments along many of the Metro Rapid lines. Officials in Eugene, Cleveland, and Seattle also told us that local governments either have in place, or are currently drafting, land use policies that are supportive of transit-oriented development. (p38)

Economic development:

Stakeholders also mentioned several factors that could lead to different amounts and types of economic development in BRT corridors compared to rail transit corridors. For instance, the greater prestige and permanence associated with rail transit may lead to more development and investment in rail transit corridors than in BRT corridors. Transit agency and other local officials also noted that BRT station areas might experience less investment and development than rail station areas because transit agencies may not own large amounts of land around BRT stations on which to build or support transit-oriented developments.43 Los Angeles city officials told us that one of the primary economic development benefits of light rail is that surplus property around the stations can be developed. Kansas City ATA officials told us that the agency owns only a few properties along Troost Avenue, which limits its ability to incentivize economic development in and around the BRT corridor. One real estate expert we spoke with noted that BRT may be better at supporting small- scale retail and residential developments, affordable housing developments, and medical facilities than rail transit, since these types of developments are often priced out of rail station-area markets. (p38-39)

This GAO report goes into great detail comparing BRT to light rail, but what about BRT vs modern streetcars? For that we can look at ongoing debate in the Washington DC suburb of Arlington VA:

The pro-streetcar group, Arlington Streetcar Now, wants to see the proposed streetcar become a reality on Columbia Pike between Pentagon City and Bailey’s Crossroads in Fairfax County (and potentially beyond), as well as a future streetcar from Pentagon City to Crystal City and then Potomac Yard in Alexandria.

It counters another new group, Arlingtonians for Sensible Transit, which launched in January. Its supporters say they want Arlington to study a “modern Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system” along the Pike. (source)

Much has been written about streetcar vs BRT on the corridor they seek to improve. A good friend, and Arlington resident, thinks the streetcar idea is “stupid” and the proponent “arrogant.” My friend also likes living very close to a Metro station, which was far costlier than any streetcar, BRT or light rail.

The debate continues….

Even though a streetcar has significantly lower capital costs than a subway system, it is still a larger investment than a BRT system, sometimes costing twice as much. For example, Arlington’s Columbia Pike streetcar’s capital costs are around $51M/mile while Lansing’s Michigan/Grand River BRT is around $24M/mile (based on estimates found on their websites). However, streetcar systems bring with them benefits that BRT systems cannot leverage. Streetcars carry more passengers, more quickly, and they attract more “choice riders” and tourists, people who typically don’t feel comfortable riding a bus. Also, streetcars signal to the private sector that that corridor is important to the community; the predictability of transit service can bring increased economic development, thereby increasing local tax revenue, and garnering various community benefits. An commensurate increase in density can create places that enable people to drive less and walk, bike and ride transit more often. (source)

I like full BRT service and BRT lite over standard bus service, but neither have the potential to generate new high-density development the way streetcars can. Regardless of mode, BRT or streetcar, other factors such as good land-use regulations are an important factor in seeing development over the long-term. We skipped this important step when we opened our initial light rail line nearly 20 years ago, and along later expansions. We must get the land-use part right this time.

— Steve Patterson

The picture above describes the following elements of BRT:

1. Separate lanes

2. Stations with shelters

3. Stations with other enhancements

4. Hybrid/alternative fueled buses

5. Longer/more doors buses

6. Low floor buses

7. More frequent

8. Fare collection before boarding

9. Branding

10. Signal priority

2,6,7,10 have no relation to the right-of-way chosen. They should be standard for all buses, not just BRT routes, to the extent affordable. There is no need to choose a particular corridor, though obviously you generally want to invest where there is higher ridership.

3,4,5,9 are pretty much worthless from a transportation efficiency perspective. Hybrid buses do not help riders. Longer buses are needed when ridership is extremely high, but no STL corridor has that, at least if you have BRT-advertised frequencies.

1 and 8 are what really define BRT. Separate lanes are cheap if the streets are wide enough that you can take lanes from cars – and in STL with its declining population that’s certainly the case. Mark off a couple separate lanes, make appropriate arrangements for parking and right/left turns (this takes some thought and political capital), and you have BRT for almost no investment. That is what makes it preferable to streetcars.

The most problematic case of “BRT lite” is when the buses do not have separate lanes (see Boston and Seattle). But all streetcars are “lite”, since they typically do not have separate lanes anyway. If so then you’d better choose the option which costs 10 times less.

I wonder how much of the reputed development potential of streetcars is due to the fact that they don’t extend outside of upper class white neighborhoods, as opposed to buses and BRT which travel the length of the city.

BRT, lite BRT, whatever. It all sounds like a bunch of mumbo jumbo. Skip the fancy stations and graphics. Why not just run a couple of express loop buses through logical, high traffic corridors? One could be generally MLK > Goodfellow > Page > Downtown, and the other could be Gravois @ Russell > Jefferson > Meramec > Gravois > Hampton > Chippewa > point of beginning. Then add a couple of feeder buses into the downtown loop and you’re done. Have the express loop buses run every ten minutes and the same for the downtown feeders do the same and you’re done.

How will it be an “express” if it is in a high traffic corridor?

Fewer stops. If the current 210 bus route stopped every 1000 feet between Fenton and Shrewsbury, it would take forever; now it’s competitive with driving.

Nobody is suggesting a streetcar between Fenton & Shrewsbury.

Neither am I, this is just an example of a current express bus route that Metro operates.

How is that applicable to the Olive/Lindell corridor being considered foe a streetcar line?

Express service on any route involves making fewer stops, making for a quicker trip for riders going longer distances. Much like Metrolink, our currently-proposed streetcar lines will operate schedules that serve every station / stop, there will be no way to skip stations and provide express service during peak times. Buses, in contrast, can easily skip stops during peak times (15 vs 15L and 0 vs 0L in Denver, 004 vs 704 in LA).

“guest” said “Skip the fancy stations and graphics” which combined with stretching out bus stops would be a significant downgrade of the service from current. You’d see a drop in ridership.

What guest said was to ADD express loops to supplement existing service, not replace existing service with just express loops (which WOULD be a downgrade for many current riders). People want to get from random Point A to random Point B. Using public transit, people can either take local service the entire distance OR they can switch to express service for the middle part of the trip IF there are good connections and save time (one huge disincentive, currently, to using local bus service to go any long distance). The cost of changing the head sign on a bus and printing new schedules is minor combined to the cost of building fancy bus stops, wrapping buses in new graphics, adding signal priority and off-vehicle fare vending.

We need to weigh the cost of all these enhancements versus the number of new riders they would ultimately attract. I’ll repeat, the two best ways to increase ridership is to make service more frequent / comprehensive and to make it cheap / free to use. Want SLU students and staff to use Metro to get between the new Law School and the main campus? Give them all passes and have plain, old, dumb buses that run express schedules that operate every 3-5 minutes between 6 am and midnight! If you don’t need a schedule and you know that you’ll only have to wait 2 or 3 minutes for the next bus, public transit becomes a no brainer. Watching the taillights pulling away as you walk out the door and knowing it’s going to be another 15 or 20 minutes before the next streetcar rolls around isn’t going to be nearly as much of an incentive.

Guest never used the word “add”, but did say “Have the express loop buses run every ten minutes and the same for the downtown feeders do the same and you’re done.”

S/he did say ” Why not just run a couple of express loop buses through logical, high traffic corridors?” I interpreted that as adding to existing service, not replacing.

But every 10 minutes, thus replacing the existing bus. It would be BRT sans dedicated lanes (a big factor in getting through traffic), special stations rather than a typical stop.

Guest here! The suggestion was to add the loops to existing service. So folks could ride the loops to head towards downtown, or connect to existing service lines. Call it BRT without the fancy bells and whistles (although a faster way to pay fare/buy tickets would be nice).

Let me make sure I understand, you want the express to run every 10 minutes in addition to the existing service? You want the express to stop every 6-8 blocks but you don’t want the stop to be fancy/special? Yeah, developers are going to climb over themselves to build densely along that route (sarcasm)

Who said anything about developers building along the route? This thread is about rapid bus transit. What’s wrong with creating a system that’s easier for existing residents and riders to use without going through all the rigmarole of full blown BRT? Look at the ridership on Disney’s rail systems. Why do people ride them? Because they get you into the park on a brainless loop system. No worry about schedule. No worry about connection. Just get on and you know you’ll get where you want to go, simple as pie. Bus ridership is unpopular because routes are hard to understand and connections are a pain. The loop system I’m suggesting creates easier to understand routes and connections.

All the streets mentioned have wide rights of way and excess capacity. Make it an express such that stops not less than six-eight blocks apart.

How will placing bus stops 6-8 blocks apart increase ridership & development?

Separate issues! If bus stops, BRT stops or streetcar stops happen every block or two, service will be slow. If they’re very 6-8 blocks, service will be quicker. Vehicle type is irrelevant. The development side depends on the number of riders, the vehicle choice is secondary to the number of riders choosing public transit.

One clarification /correction – it’s off-vehicle fare collection, not off-site. With both BRT and streetcars, you can pay at each station or stop, and not have to pre-purchase your ticket somewhere else.

That said, you’ve done a comprehensive analysis. The question that still remains is how much development is DIRECTLY tied to these large investments in “better” transit versus how much development is occurring for other reasons? Of course, transit advocates are going to claim that any investment yields results, yet there is little after-the-fact, hard-numbers analysis to back up a direct connection. (Did we build the new Busch Stadium where it is because Metrolink stops there? Is BPV being built because of the Stadium or because of Metrolink?)

The other half of the equation is system integration. Introducing a new mode to any transit system implies that many riders will be forced to switch from direct bus routes to feeder buses that require a transfer to the new system for a part of their trip. In other words, if you live and work along a new line, you’re in great shape, if not, you may end up with less / worse service, not more / better service! We have a real issue, locally, getting choice riders to ride Metro buses. We will never be able to replace every bus route with a modern streetcar or BRT, so how do we improve regular bus service for the MAJORITY of riders served (and potentially served) by local bus routes? I’d argue that more frequent service, system wide, would yield far greater results than high-dollar investments on parts of fewer than a dozen existing bus routes.

Yes, I meant off-board. I’ve corrected the post.

Off topic, but here is an interesting graph. Despite conventional wisdom, St. Louis (the city) has done remarkably well at not losing its white residents over the last 30+ years.

http://www.urbanophile.com/2013/07/20/detroit-why-hast-thou-forsaken-me-by-pete-saunders/

It’s been pretty static. I think the Catholic schools play a big part in this. The biggest loss has been blacks from NSL leaving.

Actually I generally agree with the notion that longer ride buses, not necessarily BRT can complement a transit system. In cities that I have seen with successful transit there tend to be multiple ways to get to the same destination, this includes streetcars, subways and buses. The the long ride buses between more distant stations becomes one of these layers of movement. For that to happen it means leaving the other layers in place or only modifying them to enhance the overall system.

This, along with failures in city planning are central to the struggles not only of transit, but it is also holding back the economic and social success of the region.

This leads into the question of development along these routes. Government policy has to be in tune with what is needed along all transit routes. For example the Grand Ave Metrolink station basically has a pedestrian desert surrounding it. In fact if you ride Metrolink a vast majority of stations are surrounded by parking or nothing, few stations have anything of meaningful value within walking distance. Even stations like Eager Road are an uncomfortable walk to any of the destinations surrounding it, both because of distance and the configuration of the pedestrian environment.

This is the exact opposite of what you find in successful transit systems.

Government policy needs to more aggressive in establishing the conditions for successful development along transit lines, otherwise everything will look like the current TOD development, or the lack of it, as described in a previous post.

By establishing precedent that pedestrian activity is important in conjunction with transit can be a major factor to encourage development.

Here’s my take: streetcars in the urban core from the river downtown to Clayton & the Loop. This is the urban core, & that won’t change. This is where you have the density and ridership for them to make sense. I’d also run one N/S down Grand (we’ve argued about this!).

BRT lines down all of the major roads: Gravois, Manchester, Page, St. Charles Rock rd, etc. You’d also have express busses (or BRT) going down the interstates (like Metro wants).

Then you have the Metrolink as the spinal cord of the whole system tying it all together.

Clayton? What about in SW City?

The “urban core” as I described above is the corridor of dense urbanism roughly from the riverfront downtown to 170 in Clayton. SW city–although a great place–isn’t part of this corridor.

So you’re saying North St. Louis and South St. Louis are not part of the “urban core” because they’re not in “the corridor of dense urbanism” as you describe it? Okay.

Hey, if you can call the Loop in U City the urban core, then I can call North and South City urban core, too! K?

Correct that…if you can call friggin’ Clayton, Missouri, the “urban core”, then we can sure well call the whole city urban core, period, end of story.

Downtown to Clayton is the urban core, with Gallaria and nearby shops its retail component

and Metro/hw 40/FP parkway is transportation artery

Houston – we have a problem! When people describe a suburban shopping mall and an interstate highway prime features of the “urban core”, we have a problem. Neither is urban and neither is “core”. As someone who lives outside of the haughty “central corridor”, I get sick of hearing about nothing else about the wonders of the central corridor, while the rest of the region plays second fiddle or further down the line. Some of this city’s most intact urban fabric is found in its north and south side neighborhoods. The central corridor is great, but let’s give props to the whole city, not just the chic sections.

times change. If you recognize what is the new urban core, you can better decide what is

best for the city. In St Louis’s case, dont worry about the lack of retail shopping in down=

town and clayton–the shopping has moved to gallaria, which is closer in time to some parts of the central city than downtown. Similarly, a light rail system can built on the cen-

tral core line between downtown and clayton with spurs to shrewsbury, south st louis,

westport, north county etc. This has nothing to do with someone playing second fiddle==

in all cities most people live in neighborhoods outside the central core, however it may be

defined

bus rapid was pushed by the Bush administration because of ideological influences by conservatives, who

did not like light rail (or, for that matter, did not like public transit). St Louis has had express or rapid buses

since the 1950s, running along expressways or major arterials such as Lindell, Natural Bridge, Gravois etc

Some have been cut back to connect with light rail at its outer edges. The speed of light rail exceeds bus

rapid because it is not subject to any traffic problems , particularly at or near downtown. Bus rapid may have

marginal improvements over express or rapid buses, but not much: it is really an excuse for transit planners

to say they are doing something. As to economic impact by stimulating hospital or university construction,

those are two segements which are expanding wherever they locate, and have no relation to the existence or

not of bus rapid or light rail.

I think it would be better for the ecology and the economy if public transit had no fees. If the buses are municipalized, then the people who need to get jobs could get TO them first- that’s a boon for the economy. It would also make public transit a much more attractive option than individual cars because gas is expensive.

Less drivers means less traffic for people who do drive (long distance commutes, truckers, etc.), so the roads would be safer; traffic fatalities would go down, the air would be cleaner, and the poor would save money on cars, car insurance, gas, and maintenance.

It would lift everyone up and make everything cleaner, neater, and more organized.