Soldiers’ Memorial Kicked Off Demolishing Our City’s Center

Last month, on the 28th, Soldiers’ Memorial closed for a 2-year renovation. Soldier’s Memorial is St. Louis’ tribute to those who died in World War 1.

The Soldiers Memorial Military Museum closed Sunday for a $30 million renovation, with promises of reopening in two years as a functional and inspirational “transformation.”

It is the first lengthy closure of the 80-year-old downtown landmark.

The Missouri Historical Society and local public officials held a flag lowering ceremony Sunday afternoon to mark the occasion. (Post-Dispatch)

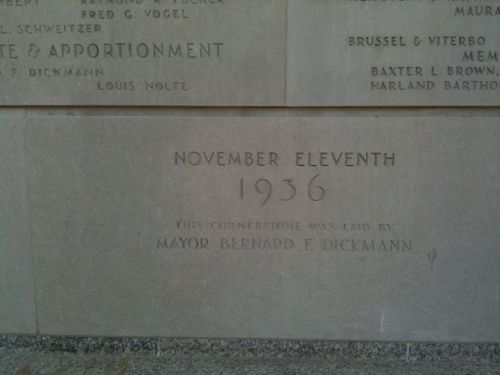

The 80th anniversary of the cornerstone isn’t until this fall. It opened to the public on Memorial Day. May 30, 1938.

The project began in the 1920s:

The City of St. Louis created a Memorial Plaza Commission in 1925 to oversee the creation of the Memorial Plaza and Soldiers Memorial. Designed as a memorial to the St. Louis citizens who gave their lives in World War I, the Memorial became Project No. 5098 of the Federal Emergency Administration of Public Works. The St. Louis architectural firm Mauran, Russell & Crowell designed the classical Memorial with an art deco flair and St. Louis-born sculptor Walker Hancock created four monumental sculpture groupings entitled Loyalty, Vision, Courage and Sacrifice to flank the entrances. President Franklin D. Roosevelt dedicated the site on October 14, 1936 and two years later Soldiers Memorial Military Museum opened to the public on Memorial Day, May 30, 1938. (Missouri History Museum — Soldiers’ Memorial)

In 1925 St. Louis hadn’t begun razing the blocks between Market & Chestnut, 11th and 20th. The Civil Courts building began in 1928, Aloe Plaza in 1931. Demolition of the original city on the bank of the Mississippi River didn’t commence until 1939. A war memorial was what St. Louis’ planner, Harland Bartholomew, needed to justify taking & razing private property just West of the Central Business District.

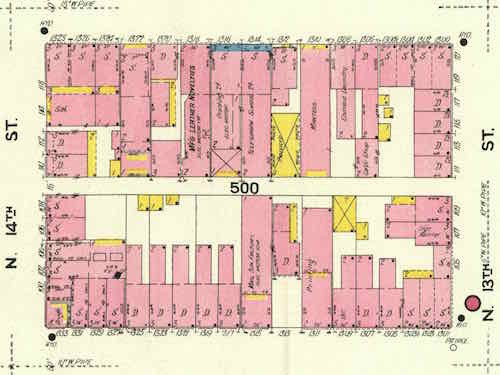

The block with Soldiers’ Memorial is bounded by 13th, Chestnut, 14th, and Pine, it looked very different in 1909:

Granted, none of these buildings were notable, no special businesses were displaced. It was rather ordinary, in fact. But this one block contained nearly 50 structures, with entrances on all four streets — it helped generate urban activity. To many born in the late 19th century such blocks were viewed as chaos.

Taking out one active block does little to change the vibrancy of a city, but when it’s repeated over and over it has a hugely negative impact. The 1940 census showed a drop in population — at least partially as a result of massive demolition in the 1930s. At the time they thought the population would continue growing — exceed a million by 1960. They couldn’t see their actions contributing to massive population declines in the coming decades.

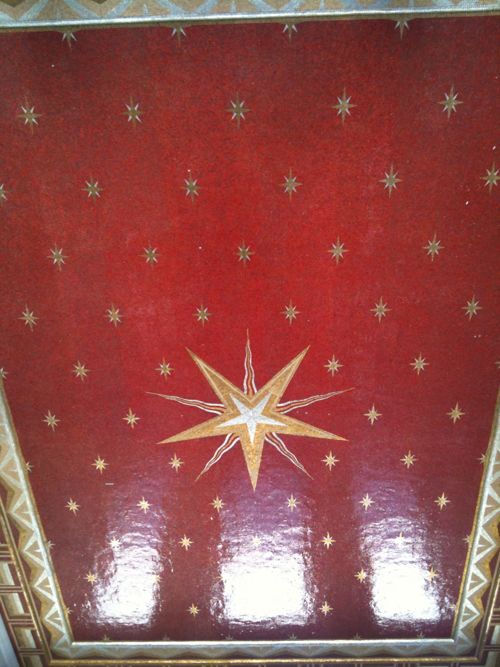

The Soldiers’ Memorial building is very formal — especially compared to the nearly 50 buildings that previously occupied the block. Let’s take a look.

Yes, St. Louis built a war memorial that many disabled veterans couldn’t visit! Not uncommon for the era — the disabled were routinely institutionalized then. Apparently the building had an outdoor mechanical lift that failed in 2004, leaving a disabled vet stranded. It was that event that prompted the effort to build ramps outside.

I love many of the interior details (floors, ceilings, rails, lights, elevator. etc) but they missed the big picture. The outdoor WWII memorial, the Court of Honor, in the block directly south also wasn’t accessible when it opened a decade later on Memorial Day 1948.

Since St. Louis has given up on the Gateway Mall Advisory Board I’m nervous above what’ll happen here.

— Steve Patterson

Good piece. See, “chaos” was good as it was the life of a city. Government “knowing better” overriding private property rights, this is when trouble starts.

Thanks. It isn’t about government knowing better — it was one persuasive man in government who thought he knew best. He didn’t. We’re more knowledgable now plus we have better processes for public input.

Bartholomew was from a generation that grew up during the rise of the industrial age — they saw cities at their worst. My grandfathers were from the same generation, but both lived in rural areas or in small towns.

It’s always one or a few driving change. What follows is often a mess. We may think that today we have better processes, but what if we don’t?. Funny thing is we always point back to those old films from when St Louis had a street life. Quite frankly, I can’t point to anything in recent history where urban planning has created such street life where none had existed our where it had been extinguished generations ago. Maybe someone can educate me. At least in St Louis, all our mega street level projects *at best* result in event spaces that are otherwise dead. We also still tear down what doesn’t fit some vision, let the public input be damned.

Good analysis, the fact the Gateway Advisory board is shut down shows the complete disregard for public input. Steve was an ideal board member in that he could, and does have discussions here at Urban Review that can sharpen his knowledge based on those discussions.

It is not the Soldiers Memorial that is the problem but rather he complete neglect connecting to surrounding neighborhoods.

This is true of many projects done in St. Louis City to date.

Basically most, but not all new projects, are garbage that fail to contribute to the surrounding environment. The latest suburban wonder is IKEA.

City leadership couldn’t screw up everything any more than if they tried.

It is unbelievable and now after sitting on the McKee project for 4 or 5 years, NGA will likely leave because the public has not been engaged in developing a type of plan will serve the future of the Northside and all city residents. Given this is a major project it should have that type of scrutiny for years.

Instead NGA sees nothing but inactivity.

The Soldiers Memorial is similar, basically the area surrounding the Memorial is dull and uninspired.

The early city builders definitely had a better understanding of the built environment. Areas where older buildings are still standing do a much job of pedestrian/human orientation than almost all of todays solutions.

The failure of public discussions is profound.

The population drop from 1930 to 1940 was also seen in some of the other top 10 largest cities in the US, including Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Boston. All of these, as well as St. Louis, then surged to register their peak populations in the 1950 census, followed by declines. While the loss of population after 1950 in these and other older cities seems to be mostly due to suburbanization, I’m not certain as to what was driving the trends in the 30’s and 40’s. Birth rates, as well as the amount of immigration into the country, did drop during the depression; although, the overall population of the US still grew from 1930 to 1940. War-time exigencies curtailed domestic auto production to essentially zero, as well as creating a significant housing shortage during the war and the period immediately after, perhaps contributing to people remaining in large cities in the 1940’s. After 1950, things were very different across the country.