A Look At The New Addition To The Eugene Field House & Toy Museum

It was nearly two years ago when I saw the elevation drawing (below) for the proposed expansion of the 19th century Eugene Field House on South Broadway.

Initially my reaction was negative, I imagined cheap materials and poor detailing. However, I decided not to share my fears. I’m glad I didn’t.

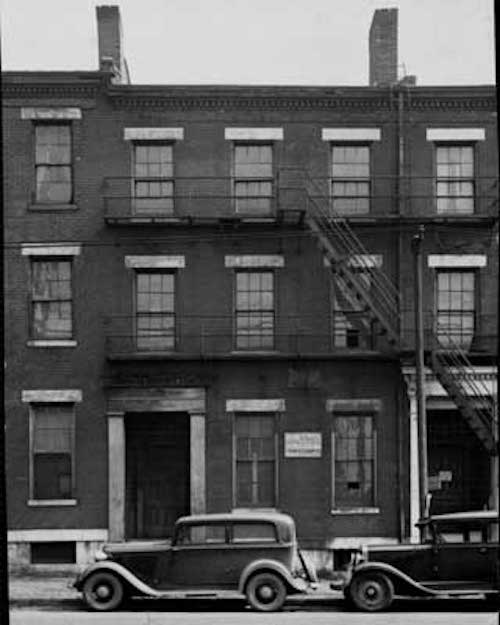

Yesterday I visited the site, still under construction, to see what I thought in person. First, we must know what used to be.

In 1936 the other row houses were razed — leaving one out of context. The Eugene Field House & Toy Museum needed to create an accessible entrance. Given enough money, they could have recreated the block. But it wouldn’t have been authentic or met their needs.

On my way there I was prepared for the worst.

I couldn’t believe that I was liking what I was prepared to dislike. Once I saw the construction sign and the architect, my disbelief immediately vanished — I’ve known architect Dennis Tacchi for 25 years.

Let me be clear:

- Razing the other non-significant row houses decades ago was a huge mistake.

- Recreating the row house facades is something best left to Disney.

- Broadway is a horrific pedestrian experience today.

- An accessible entrance was needed.

I’m looking forward to the opening and seeing the interior. Now for some more history.

Located at 634 South Broadway, the three-story Greek Revival home was constructed in 1845. Originally it was one of twelve attached houses called “Walsh’s Row”. The other eleven buildings were demolished in 1936. The Eugene Field House became a City Landmark in 1971. It is known as the childhood home of the “Children’s poet” Eugene Field.

The Field House was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2007. (St. Louis)

Poet Eugene Field was born on September 2, 1850 — 166 years ago today. His father, Roswell Martin Field, took over the Dred Scott case after the Missouri Supreme Court ruled he wasn’t a free man.

In March of 1857, the United States Supreme Court, led by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, declared that all blacks — slaves as well as free — were not and could never become citizens of the United States. The court also declared the 1820 Missouri Compromise unconstitutional, thus permiting slavery in all of the country’s territories. (PBS)

The row house at 634 S. Broadway had two significant occupants, but it’s the entire block that should have been saved. Eighty years ago a bad decision was made, we must make the best of it today. This is a tiny step in the right direction.

— Steve Patterson

Additions of this type pose an interesting challenge to architects. I like that Mr. Tacchi’s design doesn’t attempt to replicate the original structure and I applaud his use of exposed concrete, stone and brick materials in the exterior facade. His use of stone sills and lintels in the field of the front facade might have created more interest if masonry had been intentionally interrupted and inset in the area where the wood window sash would have been originally installed, as if the original windows had been removed and the opening later infilled, suggesting the window infill had not actually been toothed in, in the same plane. For simplicity, masonry at removed window opening were typically not toothed in and were set back from the facade line approximately 1-1/2″. Just an opinion. Maybe such a cold joint actually exists but isn’t obvious in the photos. And I wonder if the continuous low-height clerestory windows might have been handled differently, maybe as more vertical “punched” clerestory windows, which would have allowed the exterior walls to rise above current roof elevation a bit, providing an opportunity to maybe introduce a slight-stepped, simple parapet, which could have eliminated the flat roof and minimized the flat-roof appearance of the addition. Not being critical, just think there might have been a few missed opportunities. The addition earns an A-, in my opinion, which doesn’t mean a thing.