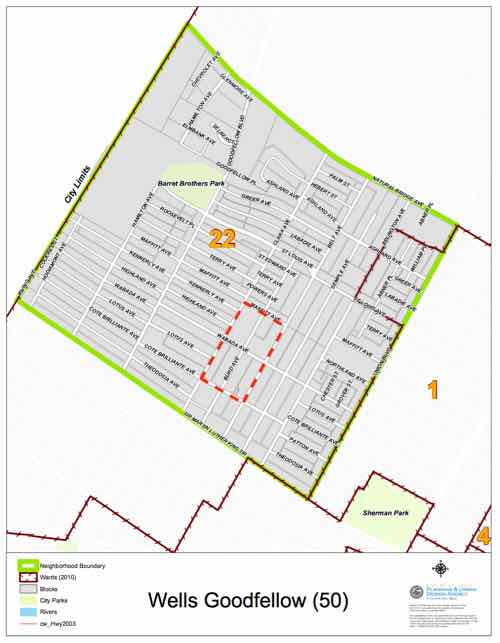

Options For The Wells Goodfellow Neighborhood

Looking at the Wells Goodfellow neighborhood last week was very depressing (see Readers Mixed On Latest Blight Removal Effort). On my visits seeing dilapidated houses being leveled I knew nobody was going to invest the money needed to have saved even one structure, let alone hundreds or the thousands throughout the city’s most sparsely populated neighborhoods.

Basically the city is partnering with a new non-profit, St. Louis Blight Authority, to clear four city blocks of vacant homes, overgrown trees, trash, etc. Occupied homes in the 4-block zone would remain.

The St. Louis Blight Authority is the organization behind a project to clear a four-block area in the Wells-Goodfellow neighborhood. The organizers believe the initiative could be just the beginning of a more far-reaching program. (St. Louis Public Radio)

Today I have a few critical observations, then I’ll offer some possible solutions.

Last week I searched the Missouri Secretary of State’s business listings to find out more about this new non-profit organization — I wanted to know structure, board members, etc. Guess what — no such organization exists! I was also unable to find a website — not even a Twitter account. Transparency is important, If we’re told a non-profit is involved that non-profit should actually exist.

Another personal observation is “Wells Goodfellow” is an awful name for a neighborhood — The “Wells” refers to 19th century transit magnate Erastus Wells, “Goodfellow” is a major north-south street — more on that later.

Wells/Goodfellow is part of an historic section known as Arlington, which takes its name from John W. Burd’s Arlington Grove subdivision of 1868. A memorable disaster in the history of the Arlington area occurred in October 1916, when the Christian Brothers College building at North Kingshighway and Easton Avenue (now Martin Luther King Drive) was destroyed by fire, one of the worst in the City’s history, taking 10 lives.

The area received its name from John W. Burd’s Arlington Grove subdivision of 1868. More subdivisions were built in the mid-1880s, with residential construction continuing until 1910. By the mid-1920s, the last of the residential subdivisions were opened. (St. Louis)

The 2013 housing development in the neighborhood uses the name Arlington Grove, so that name probably shouldn’t be used for the entire neighborhood.

Some other name with Arlington in it could be good though. Perhaps just the Arlington neighborhood? Or something to do with land developer William Burd (1818-1885)? Though Burd isn’t the most marketable name and I don’t know his politics. Was he a slave owner? His wife Eliza’s maiden name is interesting: Goodfellow.

A new name could help change perceptions for residents, property owners, workers, and outsiders. The Old North St. Louis neighborhood wouldn’t have had lots of redevelopment & new construction if it was still called Murphy-Blair.

Possible solutions for the neighborhood are varied, need to be discussed in public sessions to obtain a consensus on how to move forward. My initial brainstorming came up with the following:

- Do nothing

- Push for new infill housing

- Abandon the center

Let me explain each of these options.

1. Do nothing

This means nothing different, maintain the status quo. So tear down houses once they’ve become a major eyesore. Continue city services (water, sewer, trash, police, fire, etc) to those who remain.

2. Push for new infill housing

Try to get Habitat for Humanity or another entity to build new housing on vacant lots. It would probably make sense to concentrate new construction on one or two blocks at first. These lots are narrow so you’d need 2-3 lots per new single family house. Include some multi-family construction as well. Existing infrastructure (streets, alleys, sidewalks, water, sewer, etc) may need to be upgraded on these blocks.

3. Abandon the center

This will likely be the most controversial option, here it goes. Blocks that front onto the major streets of Dr. Martin Luther King, Goodfellow, Natural Bridge, and Union would be supported. New development would occur in these blocks only — to reinforce existing corridors. Everything inside of those blocks would be, over time, cleared. All interior streets, alleys, etc would be removed. The interior land could be used for urban agriculture or perhaps a large employer. This would create two cleared areas, one on each side of Goodfellow.

This solution is a drastic measure, but it or something similar might be the best hope for a neighborhood that has lost population to the point where it no longer functions. I don’t foresee anyone being forced to move or sell their home. Nature and economics is taking a toll quickly enough.

There are likely other buildings within the purple clear zones that could be reused within the cleared area. This area would still need water/sewer but not miles of alleys/streets/sidewalks.

Conclusion

I’ve presented a range of options, I’m sure if we put our heads together we can come up with many more.

The question I have is who will lead the effort to determine what happens next? Will it be the elderly residents who’ve stayed despite their families begging them to leave? The church leaders/parishioners who live elsewhere but drive in for Sunday services? An elected official? The nonexistent St. Louis Blight Authority?

I’m afraid the leadership vacuum will mean the “do nothing” status quo option will be selected by default.

— Steve Patterson

I’ve posted many times about day/weekend trips my husband and I have taken in small towns in Illinois & Missouri. Now we have a beautiful new hardcover book to guide us exploring more of Missouri. We especially like “two-lane” trips, as interstates are so boring.

I’ve posted many times about day/weekend trips my husband and I have taken in small towns in Illinois & Missouri. Now we have a beautiful new hardcover book to guide us exploring more of Missouri. We especially like “two-lane” trips, as interstates are so boring.