New Saint Louis University Hospital An Opportunity To Build A Great Urban Mixed-Use Campus

On Tuesday SSM Health took over Saint Louis University Hospital from Saint Louis University, at the same time announcing plans to construct a new facility:

SSM Health plans to invest $500 million to build a new St. Louis University hospital and ambulatory care center.

The new facilities, which will be situated in the immediate vicinity of the current 365-bed hospital near the midtown campus of St. Louis University, will be completed within five years, SSM officials said. (Post-Dispatch)

Uncertainty of the existing Desloge Tower left many wondering if it might be razed.

First, some background:

Going back in the history books, Firmin Desloge Hospital was officially dedicated on November 3, 1933, rising 250 feet and topped by a French Gothic roof of copper-covered lead. Over the next several weeks, it began admitting its first patients. It was unique for its time, offering patients private or semi-private rooms instead of the open ward model common in most hospitals. Desloge Tower served as the main hospital building of the Saint Louis University Medical Center until 1959 when Firmin Desloge Hospital, the Bordley Memorial Pavilion and the David P. Wohl Sr. Memorial Institute were collectively renamed Saint Louis University Hospital.

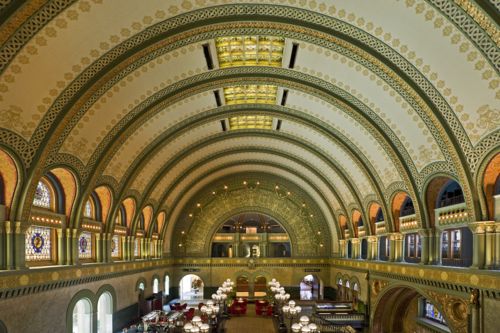

Desloge Tower is also home to the chapel of Christ the Crucified King, commonly known as Desloge Chapel, which was designed by Gothic revivalist architect, Ralph Adams Cram, who was a prolific and influential American architect of collegiate and ecclesiastical buildings. The chapel was designed to echo the contours of the St. Chapelle in Paris, which was Louis IX’s palace chapel, and in 1983, Desloge Chapel was declared a landmark by the Missouri Historical Society.

Desloge Tower continues to serve SLU Hospital with physician offices, gastroenterology, interventional radiology and the cardiac catheterization lab.

Its image is a well-recognized part of the St. Louis skyline, and is often the symbol of the hospital itself. (SLU Hospital)

With a fresh start nearby, it does mean the future is uncertain. The future of the old Pevely Dairy just to the North is more certain — it’ll likely be gone.

I’m fine with the Pevely coming down — as long as the new facilities are very urban in form. This is on the route of the busiest MetroBus route in the region — the #70 (Grand), and the #32 (ML King-Chouteau) runs in Chouteau. Just to the North is the Grand MetroLink (light rail) station.

What many in St. Louis, especially at City Hall, fail to realize is facilities can be friendly to motorists and pedestrians — these are not mutually-exclusive. The street grid need-not be decimated to create a campus.

When we visit Chicago next month, our 4th time in 2015, we’ll be staying in a friend’s condo located within the Northwestern Medicine/Northwestern Memorial Hospital campus. The sidewalks are packed with people visiting street-level restaurants. The internal walkway system and lots of parking garages hasn’t made the sidewalks a ghost town.

SSM Health is going to build a new complex. Now’s the opportunity to look at how medical campuses in other cities can be vibrant active places that are also convenient to those using cars. Dislodge Tower could become a mixed-use building with retail, restaurants, offices, and residential.

— Steve Patterson