St. Louis Blues History I Found Interesting

I’ve never seen a hockey game in person, or on TV for that matter. I never saw the interior of the old dome before it was razed. I’ve only been in the Enterprise Center where the Blues play hockey twice — both for the annual Guns ‘N Hoses fundraiser. I’m not a sports fan until the home team begins doing exceptionally well, then I take a self-taught crash course on the sport & team.

The Blues ended one of sports’ longest championship droughts Wednesday by beating the Boston Bruins in Game 7 of the Stanley Cup Final. It is the Blues’ first title in the team’s 52-year existence. (USA Today)

For a few weeks prior to the St. Louis Blues winning the Stanley Cup I began delving into hockey, the NHL, and our team. I thought about posting prior to Game 7 but if they didn’t win I didn’t want anyone to say I jinxed the chances. Today’s post is what I found interesting doing my research:

Let’s start with the Cup itself — it predates the National Hockey League.

The trophy was commissioned in 1892 as the Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup and is named after Lord Stanley of Preston, the Governor General of Canadawho donated it as an award to Canada’s top-ranking amateur ice hockey club. The entire Stanley family supported the sport, the sons and daughters all playing and promoting the game. The first Cup was awarded in 1893 to Montreal Hockey Club, and winners from 1893 to 1914 were determined by challenge games and league play. Professional teams first became eligible to challenge for the Stanley Cup in 1906. In 1915, professional ice hockey organizations National Hockey Association (NHA) and the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA) reached a gentlemen’s agreement in which their respective champions would face each other annually for the Stanley Cup. It was established as the de facto championship trophy of the NHL in 1926 and then the de jure NHL championship prize in 1947.

There are actually three Stanley Cups: the original bowl of the “Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup”, the authenticated “Presentation Cup”, and the spelling-corrected “Permanent Cup” on display at the Hockey Hall of Fame. The NHL has maintained control over the trophy itself and its associated trademarks; the NHL does not actually own the trophy but uses it by agreement with the two Canadian trustees of the cup. The NHL has registered trademarks associated with the name and likeness of the Stanley Cup, although there has been dispute as to whether the league has the right to own trademarks associated with a trophy that it does not own. (Wikipedia)

There were many decades where the Stanley Cup was the championship trophy for numerous leagues.

The National Hockey League was established in 1917 as the successor to the National Hockey Association (NHA). Founded in 1909, the NHA began play one year later with seven teams in Ontario and Quebec, and was one of the first major leagues in professional ice hockey. But by the NHA’s eighth season, a series of disputes with Toronto Blueshirts owner Eddie Livingstone led team owners of the Montreal Canadiens, Montreal Wanderers, Ottawa Senators, and Quebec Bulldogs to hold a meeting to discuss the league’s future.[10]Realizing the NHA constitution left them unable to force Livingstone out, the four teams voted instead to suspend the NHA, and on November 26, 1917, formed the National Hockey League. Frank Calder was chosen as its first president, serving until his death in 1943.

The Bulldogs were unable to play, and the remaining owners created a new team in Toronto, the Arenas, to compete with the Canadiens, Wanderers and Senators. The first games were played on December 19, 1917. The Montreal Arena burned down in January 1918, causing the Wanderers to cease operations, and the NHL continued on as a three-team league until the Bulldogs returned in 1919.

The NHL replaced the NHA as one of the leagues that competed for the Stanley Cup, which was an interleague competition back then. Toronto won the first NHL title, and then defeated the Vancouver Millionaires of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association (PCHA) for the 1918 Stanley Cup. The Canadiens won the league title in 1919; however their Stanley Cup Final against the PCHA’s Seattle Metropolitans was abandoned as a result of the Spanish Flu epidemic. Montreal in 1924 won their first Stanley Cup as a member of the NHL. The Hamilton Tigers, won the regular season title in 1924–25 but refused to play in the championship series unless they were given a C$200 bonus. The league refused and declared the Canadiens the league champion after they defeated the Toronto St. Patricks (formerly the Arenas) in the semi-final. Montreal was then defeated by the Victoria Cougars of the Western Canada Hockey League (WCHL) for the 1925 Stanley Cup. It was the last time a non-NHL team won the trophy,[20] as the Stanley Cup became the de facto NHL championship in 1926 after the WCHL ceased operation.

The National Hockey League embarked on rapid expansion in the 1920s, adding the Montreal Maroons and Boston Bruins in 1924. The Bruins were the first American team in the league. The New York Americans began play in 1925 after purchasing the assets of the Hamilton Tigers, and were joined by the Pittsburgh Pirates. The New York Rangers were added in 1926. The Chicago Black Hawks and Detroit Cougars (later Red Wings) were also added after the league purchased the assets of the defunct WCHL. A group purchased the Toronto St. Patricks in 1927 and immediately renamed them the Maple Leafs.

St. Louis wanted a team during this expansion period, but they didn’t get a team. The primary reason they didn’t was travel cost/distance/time in the days of train travel. However, after losing out on an expansion team we would get a team to relocate.

The Ottawa Senators were founded in 1883 as an amateur club. They began paying their players “under the table” in 1903 and turned openly professional in 1907. They were a charter member of the National Hockey League (NHL) in 1917, and won the Stanley Cup four times in the NHL’s first decade (and seven times prior to the league’s formation – including their time as the Silver Seven).

However, for the better part of their tenure in Ottawa, the Senators played in the smallest market in the NHL. The 1931 census listed only 110,000 people in the city of Ottawa—roughly one-fifth the size of Toronto, the league’s second-smallest market. The team started having attendance problems when the NHL expanded to the United States in 1924; games against the new American teams did not draw well. Despite winning what would be its last Stanley Cup in 1927, the team lost $50,000 for the season. The Senators asked the NHL for permission to suspend operations for the 1931–32 season in order to help eliminate debt. The league granted the request. During their suspended season, Ottawa received $25,000 for the use of its players, while the NHL co-signed a Bank of Montreal loan of $28,000 for the franchise. The Senators returned for the 1932–33 season and finished in last place. They finished last again in 1933–34 season. After the season, the Ottawa Auditorium, owners of the Senators, announced that the team would be moving elsewhere for the next season due to losses of $60,000 over the previous two seasons. Auditorium officials said they needed to move the Senators to a larger city in order to protect the shareholders and pay off their debts.

The Senators’ owners decided to move the franchise to St. Louis, Missouri, and the transfer was approved by the league on May 14, 1934. Thomas Franklin Ahearn resigned as president of the Ottawa Auditorium and Redmond Quain became president. Quain transferred the players’ contracts and franchise operations to a new company called the Hockey Association of St. Louis, Inc. Eddie Gerard was hired to coach the new team. The club was renamed the Eagles, inspired by the logo of the Anheuser-Busch brewing company, which was founded in St. Louis.[10][11] The Senators name and logo remained in Ottawa and would be used by a senior amateur team until 1954. At the time, St. Louis was the seventh largest city in the United States, with over 800,000 inhabitants— over seven times larger than Ottawa. Despite this, St. Louis had been denied an NHL franchise in 1932 because travel to the Midwest was considered too expensive during the Great Depression.

Even before the debut of the Eagles, a problem had arisen for the new NHL club. There was already a professional hockey team in the city, the St. Louis Flyers, playing in the minor-pro American Hockey Association (AHA). The owners of the Flyers claimed they had an agreement with the NHL which prevented it from settling west of the Mississippi. They threatened to sue for $200,000 in compensation as soon as the Eagles played their first game. Following a visit from the AHA President, the Flyers were asked not to go forward with the lawsuit. The Flyers did not pursue further legal action and eventually changed their home arena. (Wikipedia)

The depression was tough and the St. Louis Eagles team folded after just one season. Ouch. So when the NHL decided to expand in the 1960s a group put in an application to be awarded an expansion team? Not exactly.

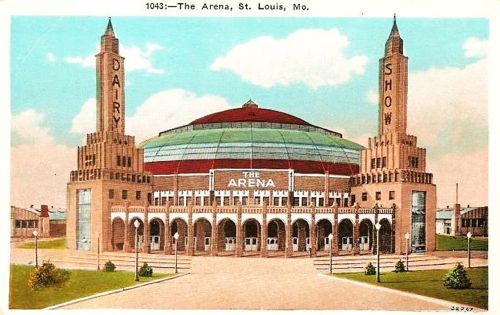

The Blues were one of the six teams added to the NHL in the 1967 expansion, along with the Minnesota North Stars, Los Angeles Kings, Philadelphia Flyers, Pittsburgh Penguins, and California Seals. St. Louis was the last of the six expansion teams to gain entry into the League; the market was chosen over Baltimore at the insistence of the Chicago Black Hawks. The Black Hawks’ owners, James D. Norris and Arthur Wirtz, also owned the decrepit St. Louis Arena. They sought to unload the arena, which had not been well-maintained since the 1940s, and thus pressed the NHL to give the franchise to St. Louis, which had not submitted a formal expansion bid. NHL president Clarence Campbell said during the 1967 expansion meetings, “We want a team in St. Louis because of the city’s geographical location and the fact that it has an adequate building.”

The team’s first owners were insurance tycoon Sid Salomon Jr., his son, Sid Salomon III, and Robert L. Wolfson, who were granted the franchise in 1966. Sid Salomon III convinced his initially wary father to make a bid for the team. Former St. Louis Cardinals great Stan Musial and Musial’s business partner Julius “Biggie” Garagnani were also members of the 16-man investment group that made the initial formal application for the franchise. Garagnani would never see the Blues franchise take the ice, as he died from a heart attack on June 19, 1967, less than three months before the Blues played their first preseason game. Upon acquiring the franchise in 1966, Salomon then spent several million dollars on extensive renovations for the 38-year-old arena, which increased the number of seats from 12,000 to 15,000. (Wikipedia)

In short, we got an expansion team because a couple of Chicago businessmen wanted to sell the Arena!

The team name of St. Louis Blues was chosen because of W.C. Handy’s song of the same name:

Saint Louis Blues” (or “St. Louis Blues”) is a popular American song composed by W. C. Handy in the blues style and published in September 1914. It was one of the first blues songs to succeed as a pop song and remains a fundamental part of jazz musicians’ repertoire. Louis Armstrong, Bing Crosby, Bessie Smith, Count Basie, Glenn Miller, Guy Lombardo, and the Boston Pops Orchestra are among the artists who have recorded it. The song has been called “the jazzman’s Hamlet.”

The 1925 version sung by Bessie Smith, with Louis Armstrong on cornet, was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 1993. The 1929 version by Louis Armstrong & His Orchestra (with Red Allen) was inducted in 2008. (Wikipedia)

Here is W.C. Handy playing the Saint Louis Blues on Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town in December 1949:

The Blues made the finals in their first few years, but never again until this year.

Deferred contracts came due just as the Blues’ performance began to slip. At one point, the Salomons cut the team’s staff down to three employees. One of them was Emile Francis, who served as team president, general manager and head coach, who convinced St. Louis-based pet food giant Ralston Purina to buy the team, arena and the $8.8 million debt. The Salomons sold the Blues to Ralston on July 27, 1977. However, longtime Ralston Purina chairman R. Hal Dean said that he only intended to keep the Blues as a Ralston subsidiary only temporarily until a more stable owner could be found who would keep the team in St. Louis. Ralston renamed the arena the “Checkerdome.” After two awful years including finishing with a franchise low 18–50–12 record with 48 points (still the worst season in franchise history) in 1979, the Blues made the playoffs the following year, the first of 25 consecutive postseason appearances. (Wikipedia)

So local corporate interests stepped up to keep the team from moving, but that changed when the person in charge changed:

Ralston Purina lost an estimated $1.8 million a year during its six-year ownership of the Blues, but took the losses philosophically, having taken over out of a sense of civic responsibility. In 1981, Dean retired. His successor, William Stiritz, wanted to refocus on the core pet food business, and had no interest in hockey. He saw the Blues as just another money-bleeding division, and put the team on the market. While there were a number of interested parties, none had the cash to do it. On January 12, 1983, Batoni-Hunter Enterprises, Ltd led by WHA and Edmonton Oilers founder Bill Hunter tendered an offer to buy the team. He intended to build a $43 million 18,000-seat arena in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan in time for the 1983-84 season While the fan base was stunned, the players were aware of this as there were being dealt brochures on December 7, 1982 as the Blues faced the Oilers that said “Saskatchewan in the NHL”. These distractions would greatly affect their performance as they entered to the playoffs with a 25–40–15 record in the 1983 season, good enough for 65 points. This led to a Norris Division semi-finals exit against the Chicago Black Hawks. Following their playoff exit, Ralston authorized the deal to Hunter’s renamed company Coliseum Holdings, Ltd for $12 million on April 21. Emile Francis would call it quits on May 2, leaving for the Hartford Whalers to become president and general manager. The Blues then fired 60 percent of its employees. The remaining staff included the accounting department, scouting staff and coach Barclay Plager. They waited for an authorization by 75% of the NHL Board of Governors for the sale and transfer of the club. However, the NHL Board of Governors rejected the deal by a 15–3 vote on May 18. The NHL felt Saskatoon was not big enough or financially stable enough to support an NHL team.

Ralston would then file a $60 million anti-trust lawsuit in US District Court against the NHL. They claimed that they broke federal anti-trust laws and breached the duty of good faith and fair dealing by voting to reject the sale and transfer of the Blues to Coliseum Holdings, Ltd. They also requested that the court allow them to give up the team and bar the defendants from interfering with the sale of the team. On June 3, Ralston announced that it had no interest in running the team anymore. Because they were not required to participate in the 1983 NHL Entry Draft they did not send a representative, which led the Blues to forfeiting their picks. The following day after the draft, the NHL would file a $78 million counter-suit against Ralston, accusing that “damaging the league by willfully, wantonly and maliciously collapsing its St. Louis Blues hockey operation.” The NHL also said that Ralston broke a league rule that an owner had to give two years notice before dissolving a franchise. Ralston called the counter-suit “ridiculous” and gave the NHL an ultimatum–if the NHL accept Hunter’s offer by June 14, Ralston would disestablish the team and sell off players and assets to other teams. The Board of Governors rejected the offer and “terminated” the team on June 13, one day before Ralston’s supposed deadline. It then took control of the franchise and began searching for a new owner. League president John Ziegler said they would try to keep the team in St. Louis. However, had the league not found a new owner by August 6, it would dissolve the team and hold a dispersal draft for the players. On July 27, 1983, ten days before the deadline, the NHL would approve the purchase of Harry Ornest and a group of St. Louis-based investors for the team and the arena. Ornest had made plans to buy the team as early as March, but built up his efforts in late June to have enough money. Ornest immediately reverted the name of the team’s home to the St. Louis Arena. To date, this is the closest that an NHL team has come to folding since the Cleveland Barons merged with the Minnesota North Stars after the 1977-78 season. (Wikipedia)

The St. Louis Blues have changed hands many times since, but always staying local. In the 90s they moved from the Arena to a new facility initially called the Kiel Center.

Congratulations to the St. Louis Blues from going from last place to first this season. Even is non-sports types can appreciate such hard work.

— Steve Patterson