Carrollton: A Walkable Suburban Subdivision In 1956

Today cul-de-sac subdivisions are designed exclusively for the automobile. For example, my brother’s gated subdivision in Oklahoma City has internal sidewalks that don’t lead you outside the gates. A major grocery store occupies one corner on the outside, but you need a car to get there.

My parents built a new custom home in 1965-66, moving in just months before I was born. I was told the streets of the new subdivision in the former farm field were still getting paved as our house was being built. Unlike where my brother lives now, we could at least reach a convenience store from a street connected to our subdivision. Had more commercial been built on land set aside by the developers we would’ve had many more options.

However, many in the St. Louis region grew up in a 1950s subdivision that planned for walking, with sidewalks and a shopping center connected to the housing. I posted yesterday about the Carrollton subdivision decimated for runway expansion at Lambert International Airport, today is a look at the thought and planning that went into it.

The following is from page 547 of the 1970 book This is Our Saint Louis by Harry M. Hagen:

When “Johnny Came Marching Home” at the close of World War II, he found one thing to his advantage, prosperity and jobs, and one disadvantage, a tremendous shortage of housing. For many returning GI’s and their prides, their first home was a rented room or shared quarters with their in-laws.

The building industry, stopped by the priorities of war, was turned loose, and developers looked to the suburbs for the land they needed to build homes. There was land, lots of land, and many home builders built square little box-like homes marching in soldierly fashion down square little streets. These houses sold as fast as they could be completed since young marrieds and young families were desperate for adequate housing.

With the convenience of the automobile, no location in St. Louis County was too distant. Sub-division after sub-division sprung up and was quickly populated.

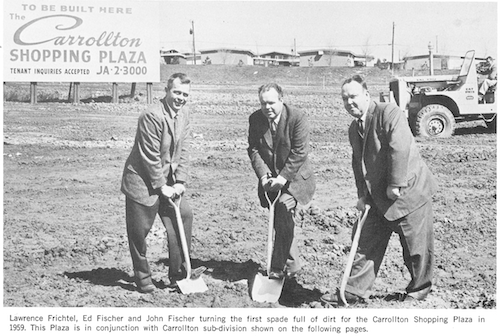

Out of this building frenzy, one team emerged with a visionary approach to suburbia. Ed and John Fischer, along with brother-in-law Lawrence Frichtel added a dimension to home building that won national acclaim for their firm, Fischer and Frichtel. Instead of building several blocks of homes in in regimented manner, they built a community.

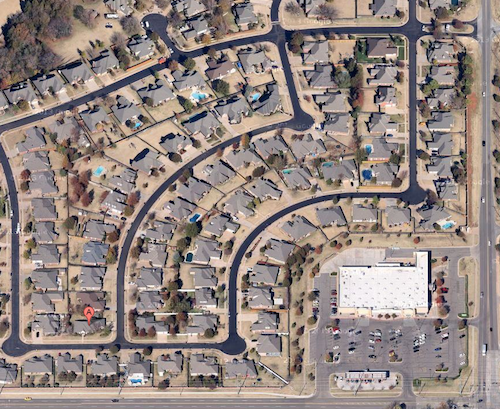

The firm amassed a large tract of land in northwest St. Louis County and in 1956 opened Carrolton, a planned community with gently curving streets, cup-de-sacs and open space. Instead of one or two home models, they offered a variety so that every other home would not look the same. They did not utilize every square foot for homes –they planned areas for churches, schools and parks that were built and used as the population grew. To make the community as self-sufficient as possible, they constructed a small shopping center so that necessities of living could be purchased within walking distance. And to complete their community, they built a swimming pool and a large recreation building, bringing free-time activities practically to the front door of residents.

Carrollton had a mixture of award-winning homes–and it was a community that offered residents more than any other single housing development in the area at that time. It was planned to make living in the suburbs enjoyable for the entire family — and its departure from the conventional set the standards followed by other developers.

Fisher and Frichtel was probably the number one home-building firm of the post-war era — and the reason for its success was simply that it gave the grass-cutting, snow-shoveling, house-painting, leaf-burning, tree-pruning public a product that was both excellent in quality and different in setting. The firm has been recognized and published in every major magazine and newspaper relating to homes, neighborhoods and conventional living throughout the country. Unquestionably, these men and their organization represent and give tribute to the great spirit of St. Louis.

Self-sustaining? Walking distance to necessities? Yes, single-family homes on cul-de-sacs can be walkable. Well, at least they tried in 1956.

However, decade after decade since Carrollton was platted, subdivisions have gotten progressively more hostile to pedestrians. I’m not sure how this happened, my guess is each subsequent generation got used to their environment and eventually only grandpa remembered walking to the store for milk.

Thanks for the book Sheila!

— Steve Patterson

I don’t agree with your all-encompassing closing statement. Yes, many new subdivisions, especially smaller ones, do little for pedestrians. But many larger, new ones include both mixed uses (retail, school and church sites) and things like sidewalks, trails and park sites – think New Town and Winghaven, here, and other new urbanist and large planned communities, across the country. I also don’t think that “grandpa remembered walking to the store for milk”, he probably remembered the milk man delivering milk to his door. Grandpa was more likely walking (or riding his bike) to the store to buy cigarettes for his mom or to buy penny candy for himself! But you are correct, we “get used to [our] environment”. One of my grandmothers never drove, my parents were a single-car family until my sister came along, and the kids didn’t have cars until we went away to college. Things are different today, especially when it comes to personal vehicles, and our built environment reflects that. I’d argue that the cul de sac, itself, is the biggest negative impact. By trying to make new subdivisions safer by eliminating the grid, we have made things less safe by eliminating the secondary and tertiary circulation paths, for both vehicles and pedestrians. Instead of having “back ways” and “short cuts”, we’re all forced onto major roads that are especially hostile to pedestrians.

I think the author Hagen has many points wrong. It’s a simplistic view without taking into account outside forces such as the GI bill, the implementation of the Interstate System, integration, crime trends, etc. Award-winning? According to who/what? The funny thing about ‘awards’ are the people awarding them and the reflection of current trends. Had Carrollton constructed LEED homes, I doubt they would have been award winning and instead would have been gigantic failures.

I think the OKC development blocks off access to the grocery store for fear that people might walk from the store through the neighborhood. There’s a socioeconomic dynamic at play there, since people without cars are typically either teenaged or low-income. It’s one thing to not have a paved path, but putting up a wall is meant to actively separate the store from the neighborhood.

I agree that it’s striking how anti-walking modern development plans are. I sold my car a few years ago in Chicago, where it’s not worth it to have a car, and STL is not quite so pedestrian friendly. Last week my girlfriend and I took the metrolink from downtown out to the Maplewood stop to visit the Trader Joe’s and other stores. The stop is primarily designed to service an enormous parking garage, with a direct path right to it. To get to the shopping destinations to the west, you have to walk way far south into an empty part of the parking lot. They could’ve easily put in a quick ramp close to the platform, but instead you have to walk an extra quarter mile south and then north to get twenty feet west and ten feet higher. The side that leads to the parking garage has a short ramp path, of course, even though that side is noticeably higher.

Then getting from the shopping center with the Dierberg’s to the one with the Trader Joe’s is impossible except from Eager Rd or an access road south of it. No pedestrian path connects them. Even though the properties are adjacent, there is a fence and a hill blocking them and there is no adjoining access. I assume they were developed by different groups, with no interest in joining them for the trivial number of pedestrian shoppers. But our trek up to Eager Rd (and across several muddy patches of lawn) took far longer than it had to.

But what’s especially striking was how little interest Metrolink had in connecting to anything but the parking garage. Despite a fifty foot banner overlooking the stop encouraging people to reduce auto dependence by using Metrolink, they created a station that is intended almost entirely as an appendage of a parking garage.

Well if one is shopping at Trader Joe’s then they have a car right? Because you know, poor people can’t afford Trader Joes and therefore don’t have cars. Sarcastic but true.

One could say Metrolink serves but 1 purpose. Get people from their cars to the Stadium so they don’t have to be intertwined with the ‘city folk’ and if they stop at a few businesses like WU or BJC along the way, it’s just a bonus.

St Louis has 2 transportation systems…bus and Metro. And they don’t mix easily.

Most cities have a problem where light rail exists for middle income people and buses exist for lower income people. And light rail tends to force metro transit authorities to siphon resources away from buses.

My main problem with buses in downtown STL is the most common places I’d need to visit (shopping in the county, or 24-hour Schnucks or Walgreens in CWE on Lindell) require me to transfer, usually from the Transit Center. Even getting to the Lafayette Walgreens requires a transfer or walking ten-plus blocks (except for rush hour, at which time I wouldn’t need it). There just aren’t a lot of routes from downtown to anywhere I need to go without a transfer. You’d think there’d be a line straight down Lindell/Olive from Kingshighway to 4th (using maybe Pine for the westbound, where necessary).

Public transit, in all forms, exists for riders from every income level to use. If you want to assume that buses are just for poor people, that’s either a judgement call that you’re making as an individual or you’re listening to too many local Luddites, who want to believe that this truly is the case. Light rail exists in most cities to move large numbers of people longer distances, while buses are used as collectors for the light rail lines or to service routes / corridors with less demand – income is NOT a qualifier.

I do agree on the whole routing and transfer issue. Many of our bus routes mirror streetcar lines that went out of service 50+ years ago. Time change and destinations change – routes need to evolve, as well, but every time Metro wants to cahnge / improve things, they always hear from current riders who like the old routes just the way they are. We either need to look at our whole system and bring the route structure into the 21st century or we’ll continue to lose riders like you me who find the current system to be highly unsuited for our needs!

I end up riding buses in most places I live. In Chicago and San Francisco, they were my primary mode of transportation. I haven’t ridden buses much in STL only because it’s easier to walk or take metrolink for where I want to go. I’m not anti-bus, I’d actually say I’m very pro-bus. But I don’t think it’s incorrect to say that buses (excluding commuter buses) are disproportionately utilized by lower-income people. That’s especially true in St. Louis, which is a very car-centric city (which is noticeable if you try to live without a car). The fact that mass transit is theoretically open to all income levels ignores the way they are designed or actually used. Commuter rails (and commuter buses) service more middle class professionals.

The actual ridership of buses tends to have a lower median income than the actual ridership of commuter light rail. Metrolink goes from suburban parking lots to downtown, suggesting it caters to people who have both decent-paying jobs and cars they need to park, as well as homes in the suburbs.

I think it’s pointless to pretend there’s no socioeconomic disparity between who uses buses and who uses metrolink. Money that goes to light rail is money not going to buses. And since buses serve a poorer ridership than metrolink, there’s an implied tradeoff to the detriment of lower income bus riders and the benefit of middle income rail riders. One study suggested that light rail is so inefficient that it would be far cheaper to buy a Prius and maintenance costs for the 7,700 carless riders of light rail. http://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/re/articles/?id=385

The reason the bus system here seems disproportionately aimed at lower-income riders is that little effort is invested in making the bus system usable or attractive in newer, mostly-better-off areas. Many Metrolink stations have park-and-ride lots, while few (no?) Transit Centers (where multiple bus routes intersect) offer much, if any, free parking. The vast majority of bus routes operate on “local” schedules, with few “express” options for riders wanting to go longer distances. You get the customers your product is marketed to, and our rail system offers a product that works better for suburban users, of every economic strata, than the bus system does. Free parking may seem to be antithetical to growing public transit, but it turns out to be a great tool to address that “last mile” challenge in low-density suburban areas, and to make both buses and rail an attractive commuting option. Unfortunately, politics and funding limit Metro’s ability to expand to match regional growth, so it’s stuck trying to serve its core area, which skews lower on the socioeconomic spectrum.

What efforts could be taken to make the “bus system usable or attractive in newer, mostly-better- off areas”? Carrots or sticks? A combination?

One, concede that most residents won’t use public transit for shopping or errands. Two, focus on offering express bus service from “free” park-and-ride lots to employment centers that require paid parking (downtown and, maybe, Clayton). Three, do a better job of marketing passes subsidized by major employers and institutions. Four, focus on frequency and easy transfers over whiz-bang technology – a bus that comes every ten minutes will see more sustained ridership than a streetcar that comes every 20 minutes. Five, provide demand-responsive (call-a-ride) service in low-demand areas instead of wasting money on trying to operate fixed-route service. And six, work to change the perception that buses are just for poor people and/or people who have no other choices!

I’ll interject with my opinion: I don’t think it makes sense to try to get wealthier riders on buses. They will mostly have cars already, often multiple cars in a household, and live in light density areas that aren’t well suited for buses. Maybe it’s cynical, but I think you’d also need to find a way to get poor riders off the buses before older, wealthier people would want to ride buses with any frequency.

It makes more sense to focus on better service for core areas and core riders. Rather than trying to change the preferences of people who already have lots of access to transportation, the transit authority should focus on better serving existing ridership sources. My sense is that will mostly consist of commuters and lower income areas. I don’t know what the commuters might want, but a local service customer (which for now includes me) would love having some sort of fare card that automatically stores transfers.

And speaking personally, I’d love if more bus routes went through downtown. It’s inconvenient to have to transfer at the civic center transit center, which is over a mile away from me. Transfers are annoying and it feels like asking for charity when you ask the bus driver for a transfer.

In my experience, buses tend to cater to lower-income people in most cities, except for commuter buses. I used commuter buses to get to work in San Francisco and it was mostly professionals; the local routes of the same bus service (Golden Gate Transit) tended to have older and poorer riders, since they were people riding a cheaper fare route and not riding at rush hour to get into the city for jobs. Commuter routes were popular for the middle class because the GG bridge had a $5 (later $6) toll, and garage parking downtown tended to cost $20 to $40+ per day depending on location; commuter buses cost $4 to $8, so way cheaper.

Generally speaking, people who can afford it will drive their own cars to work and pay to park them. Some people prefer not to drive for personal or ideological reasons, but most people like having their own space and a transportation mode that leaves when they want. It costs more, but it’s more comfortable and more convenient.

I’m currently carless by choice (for simplicity, not for ideology or poverty), but most people don’t make the same choice. I prefer to avoid the cost and hassle of car ownership, and I prefer downtown living anyway. Chicago had tons of shopping within walking distance, and bus or even the L could fill out the rest; DC made it easy to get to malls on the Blue line metro; St. Louis is not as amenable to being carless. In St. Louis I’ve had to join Enterprise Carshare just because otherwise it’s hard to access Trader Joe’s, Walmart, Old Navy, etc. Lots of people can’t make the same choice to belong to a formal carsharing program (only 8 locations in downtown, but it’s growing!). So those who can do so will get cars or bum rides; those who can’t will take the bus.

I think it’s a pretty basic rule. Cars are convenient and lots of new development, residential and commercial, is built around them because they’re a hugely popular choice for transportation. People who can afford it will usually get a car. So the people using buses are going to draw extensively on people who can’t afford cars – including the unemployed, teenagers, pensioners, those who recently wrecked their cars, and lower income people generally.

I’m not complaining about the parking garage at the metrolink stop. I’m just griping about the poor access to the adjacent shopping center. It’s a very inconsistent message; they present it as an alternative to driving, but really it’s just a subsidized supplement for car-owning commuters.

Agree with everything you say, with the added thought/question – why not use a taxi instead of hourly car rentals?

If I want to make a twice-monthly trip to Richmond Heights/Maplewood/Brentwood, then I expect to visit two to five stores. So having a car nearby will hold all our stuff in between stores. Carshare has a bunch of locations, including several within a couple blocks of our apartment – closer than the taxi stand on 8th st.

And the yearly cost is $35 and hourly is $8 (gas included free), so it’s not very expensive. Taxi farefinder guesses that the cost from downtown to brentwood promenade would be $24 to $32, so times two for the ride back. Plus extras for any intermediate trips, and no place to store our stuff between stores. And either I’m paying the cab to sit in the lot while we shop, or we need to call a cab beforehand to be waiting for us.

It’s also just more comfortable. It’s more comfortable to drive somewhere just me and my girlfriend, controlling the destination and the radio, and essentially having a quasi-private space where we can hang out. The car sits waiting for us, so we don’t need to worry about arranging a cab to pick us up, and that makes our schedule very flexible. If I want to add a stop, then that won’t cost any extra (if I already blocked off enough time, that is).

“They could’ve easily put in a quick ramp close to the platform,”

No they couldn’t. There’s not room for an ADA compliant ramp, and they aren’t allowed to put in an noncompliant ramp or stairs.

They could have put in an elevator. The real issue is that the adjacent land owner did not want access between their property and the platform, and not because they don’t want customers using Metrolink to get to them, but because they’re afraid that Metrolink riders will use their parking lot as a park-and-ride lot.

That has always been my belief. It seems silly not to

provide easy access from Metrolink to Dierbergs etc

They built a ramp on the east side. I’m sure they could make an ADA compliant ramp on the west side, using switchback if necessary. The east side is higher and they managed to make a ramp less than 600 feet long.