We Don’t Need Sidewalks…Nobody Walks Here

For 9+ years now I’ve written thousands of posts advocating for a better St. Louis. I know that getting developers to just meet the minimum requirements of our local building & zoning codes, the minimum guidelines of the American’s with Disabilities Act of 1990, etc. will not create great public & private spaces. That will, at best, make sure development won’t harm the public by collapse and not infringe the civil rights of the disabled.

To create great spaces it takes everyone (citizens, developers, business owners, architects, civil engineers, etc) looking at a site and thinking “what would make this great?” not, “what’s the least we can get away with?” We need a process in St. Louis to examine developments with respect to pedestrian access. If we did we’d see better connected projects — and more pedestrians. Let’s take Gravois Plaza as an example.

The old Gravois Plaza was razed and a new development built on the site, in December 2004 I wrote:

I’m in this area 2-3 times per week and I have always seen pedestrians taking this unfriendly route. I guess one could take the attitude that people are walking anyway so what is the big deal. However, the message to people is clear – if you don’t have a car we really don’t give a shit about you. Sure, we don’t mind if you walk here to spend your money but don’t expect us to go out of our way to do anything for you.

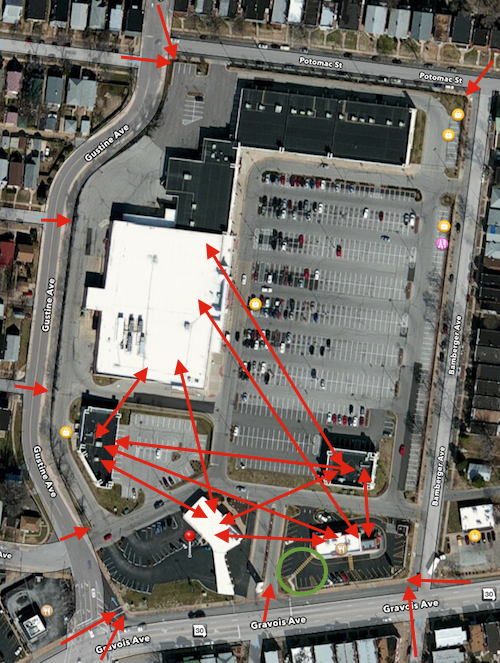

In the meantime the parking lot is way too big and has so few trees it is almost comical. How is it TIF financing can be used to finance a project that is closed to the neighborhood to the West & North, is anti-pedestrian and is mostly paving? Our city must not have any codes requiring a connection to the neighborhood, pedestrian access and even something so basic as a reasonable level of landscaping.

The old Gravois Plaza, for all its faults, was more accessible to neighbors to the North. People could enter at Potomac & Gustine and enter the courtyard space. So while the new Gravois Plaza is cleaner and features a nice Shop-N-Save store it is less pedestrian-friendly than the old Gravois Plaza.

So what would I have done you ask? Well, I would have destroyed the wall along Gustine and connected the development to the neighborhood by regrading the site. To achieve a true connection to the surrounding neighborhoods I would have divided the site back into separate blocks divided by public streets. Hydraulic Street, the South entrance along Gravois, would be cut through all the way North to Potomac Street. Oleatha & Miami streets would be cut though between Gustine on the West to Bamberger on the East. This, of course, is completely counter to conventional thinking about shopping areas.

With all these new streets plenty of on-street parking could have been provided. Several small parking lots could be provided as necessary. Arguably, less total parking could have been provided as you’d have more people willing to walk from the adjacent neighborhoods. Ideally, some new housing would have been provided above some of the retail stores. Big Box stores like the Shop-N-Save have been integrated into more urban shopping areas in other cities – it takes a willingness on the part of the city to show developers & retailers the way. The smaller stores would easily fit within a new street-grid development.

A substantial amount of money was spend rebuilding Gravois Plaza but the area is not really a part of the city. It is a suburban shopping center imposed upon the city. This could have been so much more.

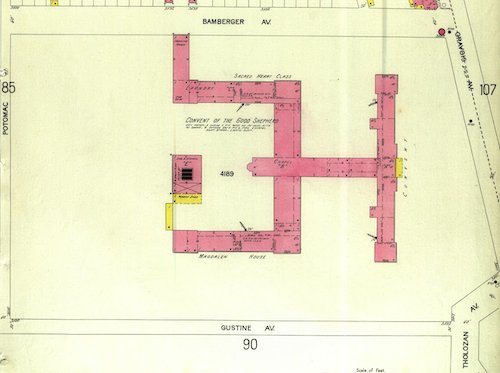

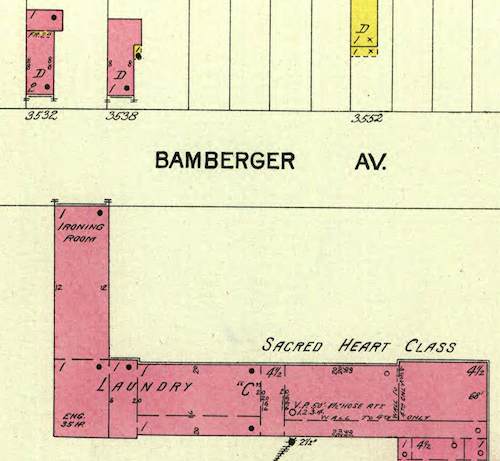

I now know the site never had cross streets, the Sisters of the Good Shepherd convent was built on 11 acres in 1895.

Click image to view on the UM Digital Library

Bamberger Ave., more connection than the two iterations of Gravois Plaza since

The original Gravois Plaza, built in 1971, didn’t consider pedestrians from the surrounding neighbors or via bus on Gravois. Thirty years later the same mistake was repeated when the site was cleared and rebuilt. In 2001/2002 we knew better but with no formal policy on pedestrian access the new project got financial help to take place.

A pedestrian policy would require an analysis of pedestrian access points and a pedestrian circulation plan. Of the five buildings on the site of the convent only one, the Wendy’s built in 2010, connects to the sidewalk. None connect to each other.

Some people, those who champion the lowest common denominator, seem to think everyone drives everywhere. They’ll point to awful anti-pedestrian areas and say “See, I told you nobody walks here.” They ignore the path worn in the grass of pedestrians finding their way to their destinations. People walk, especially to buy groceries, even if the environment isn’t designed for walking.

We live in a city where many use public transit and walk daily, why not design new development to accommodate them as well as the motorist?

It starts when a site is targeted for development. It might be an old industrial site or a place that’s been vacant for decades, so no pedestrian traffic exists. But the point of new development is to attract people — to jobs and retail services. Some will walk.

Questions to ask at the start:

- What direction(s) will pedestrians come from to reach the site? Can we anticipate more pedestrisns at some arrival points versus others?

- Will the site have more than one building when fully built out? How will each be reached from outside the site and from each other?

- Can we make the design pleasant enough that people walk to the site rather than drive, allowing for a reduction in the amount of surface parking needed?

- Can we arrange the building(s) so those who arrive via car to park and walk from store to store?

- Can planter areas next to the pedestrian route(s) be used to catch & retain storm runoff?

It costs little, does no harm, to ask these questions at the earliest stages of a project. Asked later and the answer is likely to costly to make changes. Never asking them risks a ADA discrimination complaint.

We can build better developments that are welcoming to everyone, and don’t need a new government incentives to be razed and replaced 10-30 years later!

— Steve Patterson

My problem with City of STL is emphasis always on South side. I will never buy in City of STL for that very reason! No parody between north and south, but taxes the same!

There are fewer developments to critique on the north side, but I’ve written about a few over the last 9+ years: MLK Plaza, Roberts Village, etc.

McKee’s Northside Regeneration is a prime candidate for the type of input you’re seeking, and the timing couldn’t be better. Now, how do we make that happen?!

It has been happening behind the scenes for a couple of years already. But I want a transparent policy to be applied consistently, not project bt project.

Taxes are not the same. I live on the south side, and I pay way higher property tax than someone does on a similar house on the north side. About triple.

That would be parity, not parody . . . . Freudian slip, perhaps?

You may be surprised, but I agree with both the general need for good pedestrian access and the “questions that need to be asked at the start of the project”. My real concern is whether the “questions” can and will be answered honestly, with empirical data, so that the results will match the predictions and the assumptions, beefing up pedestrian infrastructure, where it’s needed, and scaling back, where it’s not needed. Where we differ is both in the priority that pedestrians should play in the hierarchy of design decisions and, especially, on how often most people are going to choose to walk to the grocery store. Businesses can’t afford to invest in a lot of sidewalks that might be used by only a few people a week; both businesses and government SHOULD invest in a connected sidewalk system that will be used every day!

Yes, this is a great example of poor pedestrian connections. This is also a great example of how land uses evolve over time and how assumptions can sometimes be wrong (the street grid never existed, which made the site attractive for this type of development). This is also an example of too little landscaping, poor site circulation, for both vehicles and pedestrians, and a project that is both out of scale with and poorly integrated into the surrounding neighborhood. The real challenge will be figuring out how to get these questions asked, by the appropriate people, early enough in the design process, so that the “right answers” come out and are reflected in better designs actually being built. The Wendy’s is the newest part of this puzzle. It’s better – why?! Is city staff getting better? The alderman? The architect, who sees more stringent requirements elsewhere across the country? The property owner, who sees a need to have a better project to stay competitive?

I think the design architect of this shopping center, as well as most others, ignore the first impression a car only center gives. It looks like a fort meant to keep people out. Pedestrian access, if you use it or not, can easily soften the appeal with few changes. Does it really cost that much to pop in a thought-out pedestrian access in a redevelopment of this size?

Exactly, they started with a clean slate so it would’ve been fairly easy and inexpensive to incorporate pedestrian access. The Penn Station & CiCi’s Pizza chains have both closed here, already going downhill. Pedestrian access would’ve given this development a longer life.

Just a note that Anna’s Linen’s — a discount Linen’s N Things type store — has opened up here I believe in the old CiCi’s Pizza spot and arguably provides a better service for the area than fast food.

Also, it is interesting to see that a youth addiction facility will be going up on Gravois a few blocks east in the vacant lot next to the Southside Bank tower. It would have been nice if that spot could have commanded mix-use, mid-rise development but its nice to see infill there.

The “design architect” for any shopping center starts with a list of goals and a list of governmental requirements. The owner’s goals include maximizing rentable square footage, making the spaces attractive enough and flexible enough to fit a range of tenants (if it’s speculative space) or to fit the specific requirements of a defined user (if it’s build-to-suit space). The governmental requirements include access points (highway or streets dept.), number of parking spaces, dictated by rentable area (zoning), accessibility (ADA), building setbacks (zoning), drainage (MSD), and in areas with more stringent requirements, various design elements, like materials, massing, “style” and landscaping (zoning, planning, developement’s ownership). Pedestrian connections, beyond the basics the government may require, are rarely a priority unless the project is located in a CBD. This has nothing to do with any hate or disrespect toward pedestrians or transit users, it has everything to do with the basic fact that 95%-98% of the shopping center’s tenants’ revenues will be coming from customers who will be DRIVING!

The reason most of these developments “look like forts” is for two big reasons. One, because most immediate residential neighbors want it that way. They don’t want the lights from the parking lot shining in their windows. They don’t want customers or employees parking in front of their homes. They’re perfectly fine being physically separated from the retail activity. And two, most businesses operate with little staff, so they want only one public entrance. Given that most customers will be driving, most tenants want that entrance to face the parking lot, not the public sidewalk along the main street and they don’t want a second or third public entrance remote from the first. They want the back secure – no windows, solid walls and doors, for deliveries and emergency egress, only. The result is what we see here and pretty much everywhere else, outside the CBD – parking lot in front, with retail buildings facing one or more sides of the lot. These predictable design decisions are being made because they result in consistent rents, high occupancy rates, predictable construction costs and a predictable permitting process. No, they’re not great urban design. No, they’re not great architecture. No, they’re not very pedestrian friendly. But they work – most people, in this century, choose to shop in boring strip shopping centers, just like this one (when they’re not shopping online)!

Whether it’s because their customers don’t have other choices or because they’re lazy or stupid, the stores with free parking out front tend to do better than those that don’t, period. And most business owners don’t want to risk their profits on “doing the right thing” for pedestrians if it means alienating or discouraging their customers who drive. That said, there is no reason why pedestrians should not be included. Every strip shopping center has a sidewalk between the storefronts and the parking lot – connect it with the surrounding neighborhoods! Provide a continuous pedestrian path to every front door. In this example, how hard would it be to include a defined pedestrian connection at the northeast entrance, off Bamberger? How hard would it be to connect Anna’s Linens, the bank building and the eyeglass building with sidewalks and marked crosswalks to the existing public sidewalks, somewhere along the property line?!

It’s probably already in the building and/or zoning code (if not, it should be), the trick boils down to enforcement. Maybe it’s as simple as empowering an existing city employee (or hiring a new one) to be the pedestrian watchdog. Have them review every plan, make them responsible for compliance, especially the missing connections. What happened here was “approved”, at some point, and likely more than once, by our city staff. Yes, the developer and his or her design architect” should have done better. But unless and until there are any negative consequences for not providing appropriate pedestrian connections, it ain’t gonna happen on any sort of consistent basis. And it’s those near misses, like the one at the Bamberger entrance that DO provide an unnecessary yet subtle disincentive to walking. And no, it does NOT “really cost that much to pop in a thought-out pedestrian access in a redevelopment of this size”. However, it will only happen if some level of city government REQUIRES IT; until then the lowest common denominator will continue to prevail – “if it’s good enough to get a permit . . . . ‘

Some drive simply because it’s not designed to walk to. We’ve tried the laissez faire way for too long and all we get is bottom of the barrel crap like Gravois Plaza, Southtowne Plaza, Loughborough Commons, etc. It’s time for government regulations to require good pedestrian access since the developers, owners, architects, engineers, etc wouldn’t do it on their own.

I agree that we need more comprehensive regulations. How do we make that happen? How do we get the Board of Aldermen to pass the enabling legislation, fund the position(s) and, most importantly, let city staff enforce the laws’ requirements, without meddling? I’m obviously most familiar with how things are done in Denver: http://walksteps.org/case-studies/denver-pedestrian-master-plan/ . . http://www.denvergov.org/developmentservices/DevelopmentServices/CommercialProjects/SiteandDevelopmentPlanReview/tabid/436366/Default.aspx . . http://www.denvergov.org/Portals/696/documents/SitePlanReview/Formal_Site_Development_Plan_Checklist.pdf . . (Page 8, Item 9) and http://www.denvergov.org/Portals/487/documents/Standards%20and%20Details%20Updated%20071505.pdf . . If we don’t require something similar, here, I agree, we’ll continue to get substandard results. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/14/us/denver-pedestrians-promote-walkings-urban-potential.html?_r=0

Steve, you’re making a rather hollow point when you say GP, SP and LC are bottom of the barrel crap. In each case they are replacing and vastly improving what was on all of those sites prior to their reuse.

Gravois Plaza was a horrid Kmart. Southtowne Plaza was built on an eyesore vacant lot that stood vacant for nearly ten years. And Loughborough Commons was a tangle of mostly obsolete industrial buildings sandwiched between a residential neighborhood, an interstate highway, and a city park – not a pretty entrance to the city or a neighborhood.

The city is better off for all three of these developments compared to the state it was in prior to them. Your recent poll asked the question, “Is the glass half full, or half empty”. These three developments help fill that glass. Had none of these projects happened, and had all three of the sites remained in their prior to reused conditions, then that glass would have been bleeding dry.

Especially in the case of Loughborough Commons. You are a loud and frequent critic of that development, but many people think it is one of the best things to come to South St. Louis in years. All the businesses there are high credit worthy tenants, provided much welcomed and needed services to local and County residents.

Not long after the completion of Loughborough Commons came the new YMCA Community Center and pool to Carondelet Park. New shopping centers and quality community facilities help attract residents and make our city more livable.

As we enter 2014, let’s keep moving forward. Let’s keep pushing for good things to happen. Let’s get more engaged. Let’s work together. One of the best things about St. Louis is that it’s not perfect – it’s a work in progress – just like each of us is a work in progress. And here in St. Louis, we have the opportunity to be a part of making this place a better city, and we do, we make ourselves better people.

Happy New Year!

True these kinds of developments work, except (as in this case) when they don’t. Classic example of one size fits all development.

What you would have done doesn’t matter. The residents of these neighborhoods spoke about what they wanted back then at the many open forums. Pedestrians? Please, the only pedestrians that were there, especially back when this was first proposed were those that either could not take a bus or didn’t have a car. NO ONE will walk in any area no matter how pretty the sidewalks are if they are going to get mugged on the way home, and that is exactly what was happening back then and happens now. Not just here but at any place. And few people are going to take time out from their busy day to walk to the grocery store to buy a few items. They make a weekly or biweekly trip…..that means lots of packaged. That means a CAR or the Bus. But I’m sure you know that because you appeared at the various forums and talked to the Alderwomen. Oh wait, you haven’t. You’re just guessing.

Penn St and CiCi’s…..they didn’t close because of lack of pedestrians. They closed because of lousy food and/or too high price points.

You do know that a person walking from the nearest bus stop into the development is a pedestrian? And the stores there need more customers & employees than the handful of people who showed up any meetings about the development.

No I didn’t know that. I thought they just flew in or used their transporters. What you don’t want to acknowledge is that right or wrong, the neighborhood spoke….those be voters. Just like they do about wanting a Wally World in Shrewsbury, the Whole Foods in the CWE and everyplace else. You also fail to acknowledge the historical influences that go into these decisions….and yes, even just a few years ago is “historical” considering the crime/poverty/owners/renters/bus usage and a host of other factors that go into these developments. . Very little happens in a vacuum. But then again, you consider anything a vacuum that doesn’t invite and listen to you.

St. Louis is a vacuum because so many natives are closed minded to anything different than how things have been. You exemplify this mentality daily!

“What you don’t want to acknowledge is that right or wrong, the neighborhood spoke….those be voters.”

yes, i’m sure the developer said “do you want this development to be walkable?” and the townsfolk all raised their pitchforks and said “NO! We HATE walking!” more likely the developer didn’t offer, and in true St. Louis form everybody said “Welp, we better take whatever we can get! ANY development is better than NO development!”

“And few people are going to take time out from their busy day to walk to the grocery store to buy a few items. They make a weekly or biweekly trip…..that means lots of packaged. That means a CAR or the Bus.”

i’m sorry but this is priceless. have you ever traveled outside of St. Louis?

“Penn St and CiCi’s…..they didn’t close because of lack of pedestrians. They closed because of lousy food and/or too high price points.”

“Oh wait, you haven’t. You’re just guessing.”

I once emailed Jennifer Florida why that development was built with so little pedestrian access and her reply was: “KIMCO developed Gravois Plaza. If you have any suggestions for pedestrian access, I will be happy to recommend them. The shopping center was designed for motorists.”

Not really a satisfactory answer. But I’ve also come to believe that it wasn’t well designed for motorists either. Entering by car on the Gavois side is awkward and odd with too many intersections. The intersection to the lot nearest the bank on the southeast corner of the lot has a weird bend that is confusing.

So it’s not a good design for pedestrians or motorists!

And that lot is way too big. I’ve never seen it more than about a third full–and that’s rare.

This post illustrates beautifully one of the greatest frustrations for so many people in St. Louis. (Understand I don’t normally type anything in all caps..) ALDERMEN ARE NOT THE ANSWER!!! Ahem…Thank you. I feel much better now! (I will add, however, that if it is leadership and vision you are seeking, then, yes, by all means, pick your alderman wisely!)

I guess I look at this like suggestions about the types of stores that a developer should lease to or the type of exterior decoration a developer should use. Reasonable criticism, but it’s the developer’s mistake to make. Deciding to focus retail on grocery or clothing or organics is a choice, as is deciding the balance between focusing on which sort of customers and what sort of transportation. Parking lots typically aren’t built to favor motorcycles, bicycles, segways, walkers, or semi trucks. Some parking lots have lots of motorcycle space, some have big semi truck space, and others are simply nonexistent. I don’t think there needs to be a central policy to decide on the right balance to strike here. This is the sort of thing that can be decided thousands of times by individual consumers, developers, landowners, and the like. If they decide that it’s valuable to focus on driving customers, but not worth their time to make life more convenient for pedestrians or semi trucks, so be it – it’s not our place to override those choices.

I say this as somebody who has spent a lot of time walking and riding buses and doesn’t own a car. It’s just more convenient to drive a car, in most situations, and it’s the sort of thing that most people can afford. Retailers and developers understand that, so they offer parking to draw in drivers and they often neglect to even consider pedestrians. That’s their fault, same as retail clothing stores that charge fifty dollars for a t shirt or organic food stores that charge enormous markup on every item. These sort of choices don’t need to be made centrally and shouldn’t be so.

The centralizing mentality to dictate more walkable neighborhoods is no different from the centralizing mentality to knock down urban neighborhoods to build freeways, it’s just the same impulse in service of different goals. The people who knocked down “blighted” neighborhoods to build roads, parks, or the Arch grounds though that neighborhoods full of poor (usually minority) people in low income housing thought they were shaping a better world by imposing their vision on it. But in the process they ejected people in most major US metro areas from downtown areas considered too crowded, trying to get them to move out to bigger suburban plots (or to leave the area entirely). Many planners imposed setback and housing density rules to prevent urbanization from spreading. Now planners want to discourage the move towards more spacious suburbs and rebuild crowded areas that previous central policies had neglected or demolished. Many people, contrary to setbacks, want to create sidewalk rules forcing retailers to be streetfront and pushing parking lots to the back or otherwise away from the sidewalk.

Rather than reshaping society in new ways all the time, I think the best solution is to let every homeowner, landlord, retailer, and developer make these sorts of choices and let a metro area develop naturally. Yes, it will be messy and some people will not get as much consideration as they want, but there’s literally no scenario where those two things will not be true. All a political solution can do is zero-sum redistribute the existing pie in favor of whatever groups manage to hold sway with the politician.

I disagree, the city is the one that determines the type of development that takes place or not, through zoning. Development should be accessible by everyone, not just those arriving by car.

I don’t think there’s any reason to think the city will find a better balance than anybody else. The city will create rules that serve the interests of favored constituencies, but only at the expense of others. Maybe at the margins they’ll make some suggestions or mandates that help more than they cost, but I’m skeptical that this could ever be done reliably.

As I said, I don’t see why a development must be made to better accommodate pedestrians, but not to accommodate bicycles, motorcycles, or 18-wheelers. It’s all an arbitrary balance, so I think the fairest solution is not to mandate a single balance for everybody.

Furthermore, this developer like all the others, came to the city with their hand out. They couldn’t do it alone. They needed help. The city should demand better.

It’s a fallacy to suggest that just because the city offers assistance to developers, that city conditions should be increased. Assistance is needed because it’s harder to do any development in older neighborhoods, often on brownfield sites, with weak market conditions, and tired infrastructure.

That’s what the assistance is for – to help overcome the added challenges to carry out urban redevelopment. It’s not about making it even harder by adding more restrictions on top of other challenges.

Also, urbanists often fail to mention (or do not really understand) that even without added design controls, city assistance to developers often triggers rigorous minority and women business participation requirements on projects, increasing development costs and red tape.

Agreed, we need to require pedestrian access regardless of any government assistance.

Uh, that wasn’t the point. Yes, ADA should be met. Adding more and more better pedestrian access should be at the developer’s option, not by fiat of government.

Government regulates every but of the development process from types I’d tenants, to the size & number of parking spaces. Our zoning mandates vehicular access but not pedestrian access.

So you’re advocating for more government regulation? The books are already hundreds of pounds of regulations. Maybe a few hundred more would stimulate the local market? Rubbish!

No, I’ve long advocated toltally trashing our cumbersome 1947-era Euclidean (aka use-based) zoning code and adopt a form-based code. In doing so pedestrian access would fit right in. This would offer simple diagrams about what’s desired, it’d be significantly easier to understand and follow. The results would be a boon for the city and developers.

Two questions. One, what has been the experience in other cities that have enacted form based zoning? I know that Denver did that a couple of years ago, but I don’t know what the impacts, good and bad, have been. Are things actually “better”? Was it worth the effort? Or, is it just a different way of getting to the same results?

And two, I get it, you’re a strong believer in pedestrian infrastructure. How do we accommodate other people’s passions, when they also represent distinct minorities? Do we need to have the government mandate specialized stuff for everyone? Bike lanes and bike racks? Hitching posts and watering troughs? Dedicated parking for motorcycles, oversize trucks, expectant moms, the elderly and the obese? Bigger typefaces for people who have a hard time seeing? How about restrictions on tacky design elements? Requirements for energy efficiency? Requirements for (brick) or prohibitions against (wood shake roofs) specific materials? What is the rationale?

All of these items invariably carry higher, additional costs. The government’s role is (should be?) to protect the public’s “health, safety and welfare”. When do requirements move from the basics to frills? When do the added costs impose unreasonable burdens on individuals, as opposed to reasonable requirements? All of these things are “good” to do, but why should everyone be forced to do them? What is the basic government purpose versus busybody meddling? Do we have the right to be stupid, to make mistakes? Or do we need a nanny state watching out for our every move and every need? Do businesses need to be told what they need to do to reach enough customers to be successful? Or, should we require that they spend 10% more for 2% more income? If you’re a part of the minority, the answer is, obviously, yes. If you’re a business, with a budget, expenses, competitors, employees and fickle customers, the answer is much less clear. But given the small profit margins inherent in most businesses, there will always be a tipping point where regulations WILL become too expensive and businesses will decide they’re simply not worth the cost, and nothing will be the result, not “better”.

Zoning has been around since the early 20th century, a tool used to codify how an community wants to develop/redevelop.

Currently our zoning conflicts with other public policy: ADA, efforts to reduce greenhouse emissions, efforts to support public transit.

If our current used-based zoning code with minimum parking requirements was put into graphic form the public would be appalled. But it’s page after page of very confusing language.

A form-based code won’t be free of problems, but it’ll be more transparent and will yield better physical results that function appreciably better for everyone.

The law is confusing and twisted because it’s shaped and implemented over a long period by a large group of political leaders and bureaucrats with different goals and intentions. A lot of early zoning was used to further efforts at segregation, and even today a lot of zoning and planning is used to control the perceived affluence of many areas and communities.

So while it may be helpful to enact a whole new zoning code, the process of implementing it will require buy-in from various groups of politicians – many of whom are currently relying on the existing twisted rules. Then it will have to suffer implementation by clerks and bureaucrats used to the old system and who will find it simpler to rely on old habits and unwritten rules of thumb. And of course politicians will find new ways to adjust the code over time, making it look less and less like the intended vision and more like a path for politicians to reward allies and punish the intransigent.

You can fix the code, but the people who enforce it and re-write it are inescapably going to put their mark on it. And if the system is too rigid against their influence, then they’re less likely to accept it in the first place. The only sure way to avoid complicating and politicizing the zoning process is not to have one.

I’ll repeat – where are the success stories, from where it’s actually been successfully implemented? When I google “form-based zoning success”, all I get is a wikipedia article with multiple flags. And when I google “form-based zoning St. Louis”, I find that we already have a form-based zoning ordinance, apparently available as an option, with multiple paragraphs of “confusing language”: https://stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/mayor/initiatives/sustainability/Sustainable-Policies-and-Ordinances.cfm . . http://www.slpl.lib.mo.us/cco/ords/data/ord9199.htm . . Has it been implemented? Is it working?

New is not necessarily better than old. Conflicts can, do, and will occur under any zoning – that’s why there’s a process to both modify it and to provide case-by-case exceptions. You make the blanket statement that switching to form-based zoning “will yield better physical results that function appreciably better for everyone”, but I’m a cynic, where’s your proof? Or, can we just (continue to) modify what we already have (less required parking, smaller or no setbacks) instead of throwing everything out and starting over? (And to answer one of my previous questions, yes, it does seem to be working in Denver: http://www.bizjournals.com/denver/print-edition/2012/06/29/denvers-new-zoning-code-delivers.html?page=all . . but it was not easy and it still remains a complex, ‘700-page zoning code’!)

I’m more than willing to concede that our current zoning has problems, that it’s complex and that its parking requirements have unintended consequences, especially for new construction (not so much for new uses in existing structures). But our current zoning also does not preclude doing much of what would happen under form-based zoning, either. Denser commercial districts already allow structures to be built to the property lines and our aldermen seem to be pretty amenable to working with and granting exceptions for many new projects. Plus, zoning rarely addresses sidewalks, especially on private property, so how would a new zoning code make things better for pedestrians, “reduce greenhouse emissions [and assist] efforts to support public transit”?

Our fundamental challenge, in much of the city and most of the region is LOW DENSITY development! Zoning is not the “problem”, economics and land values are! Zoning sets minimums and maximums, but it cannot (and should not) demand that every project SHALL be constructed to meet those smallest minimums and those largest maximums. If zoning says that you can build 200,000 square feet of enclosed space (because of parking requirements and lot coverage ratios), you can (and should be able to) choose to “only” build 80,000 or 50,000 square feet. If you live in a downtown loft and there’s a surface parking lot next door, should that property owner be forced to build a multi-story structure and fill up the site, to significantly increase density? At the expense of your views and access to sunlight? Should we forego IKEA because half its site will be paved? Should we force developers to build TOD’s if our transit systems are inadequate or non-existent? I get and support your goal of a more walkable and more urban St. Louis, I’m just not sure that a whole new zoning structure will yield the results that you desire, especially given our current land values . . . .

One of the original success stories is Seaside Florida. The code guided development over the years to achieve a desired form.

Seaside was a blank slate with a single developer, much like New Town St. Charles. It’s a great example of a planned community with tight design controls. My question is how well does that translate to an established, historic, urban city like St. Louis? A city with multiple developers, multiple individual agendas, multiple building types, limited economic resources and a recent history of relatively weak planning efforts?

It doesn’t. At this point, form-based codes are only being sought in the areas with the highest market values (CWE and parts of 17th and 28th wards).

The need fpr a clean slate as a means pf tight controls was the purpose of the

much maligned urban renewal program(Mill creek). As that became unpopular, strategy

moved to benign neglect, which has now emptied out enough of the eastern

north side to allow the McKee redevelopment

Developers ask for money because political leaders like to give it. In any case, I’m not crying out for sympathy on behalf of real estate developers. I’m saying that planning and zoning policies tend to enforce rules that are inflexible and tend to survive long past their obsolescence. And they increase the cost to build, creating greater demand for city handouts – in a sense, the city has to subsidize its own planning rules by cutting into the tax base.

The 15th ward alderwoman was very proud of this development. Obviously this type of planning is not a priority or strength. This issue might be better discussed at the next election to assist in electing someone who has the ability to make these priorities part of urban planning.

I, for one, do not think that we can or should expect to elect very many aldermen who are well versed in urban planning. That’s why I keep saying that we need to empower professional city staff to lead this effort, not one of two dozen elected officials who have no educational requirements, little experience (in urban planning) and are likely to be more interested in delivering short-term “results” than in looking at any sort of bigger-picture agenda!

Alderman do not develop these sites.

You are right the developer does. The alderwoman is part of the process, though.

To what extent? What control does an alderman have over what a developer builds?

Well, of course there’s no answer to this question, because it’s unknowable. First of all, any developer who thinks an alderman is somehow greasing the skids to get development approved is a fool. No business decisions should be based on such political machinations. Second, any alderman who puts pressure on a developer to build according to an alderman’s whim should be exposed as a thug. No alderman should “control” what a developer builds.

Any alderman proclaiming “they” are the ones developing squat (when it’s really a whole cadre of professionals and others making things happen) and then having obsequious residents/voters actually believing the garbage narrative of alderman being the rainmakers of all are just feeding a long-standing, dysfunctional, St. Louis narrative. Good aldermen understand this; weak aldermen perpetuate the dysfunctional narrative to maintain hold over their ward “fiefdoms”.

Real progress comes from collaboration, professional planning, creative financing strategies, vision, leadership, and community support. That’s a whole lot more than an alderman doing whatever.

I don’t think anyone is suggesting that the alderman demand developers succumb to their whims. That’s a complete misrepresentation of the point of mentioning an alderman in this conversation. An alderman should be the representative of community interest in a development and part of the collaboration you talk about in the last paragraph of your comment. Obviously that didn’t happen with this project. I don’t think anyone is saying that the alderman is the sovereign ruler of the ward. To suggest otherwise shows some ignorant condescension on your part.

Problem solved: http://roadtrippers.kinja.com/meet-the-most-killer-mobility-scooter-ever-made-1493931783/@Coop1930

Remember when Steve Wilke-Shapiro redesigned the Schnucks site on Grand and Gravois to make it more pedestrian friendly and better integrated into the surrounding environment? He took the time to do a number of drawings if I remember correctly. You did a post about it Steve. He took the time to do several drawings if I remember.

There is no doubt that Gravois Plaza could be designed to be more friendly and useful to those on foot and transit users. Although I have to agree with the comment that it isn’t such a great design for cars either.

It really comes down to whether or not there is a commitment to build a better city, one that includes the needs of human beings and not just the automobile.

The time to design was back when the site was being redeveloped. While it’s a great intellectual exercise to create better scenarios now, the likelihood of anything changing is pretty remote, absent the whole center being vacated. As long as there’s a profitable grocery store (as an anchor) and several successful uses on the out lots along Gravois, the inertia of the rent rolling every month, combined with new projects to develop, elsewhere, pretty much insures the status quo remaining unchanged. Making changes, now, would mean inconveniencing current shoppers (who apparently have few problems with the current arrangement), while generating little in new revenues. We need to get ahead of these projects, not just point out their flaws once they’re open!

Agreed, I was just using Gravois Plaza as an example of how the site planning could’ve been analyzed up front. Unfortunately we’ve built a lot of new developments over the last 20 years without doing this.