Readers Split on Giving the Chronically Homeless Apartments

My views towards homelessness have changed over the years; I wasn’t a supporter of the “housing first” model, it didn’t make sense to me. Now, after looking into it with an open mind, I see it is very logical. We know from decades of experience that how we’ve been attempting to address the issue of chronic homelessness hasn’t worked, requiring the chronic homeless to jump through hoops doesn’t work. and is costly and detrimental to the community at large. A different approach is needed.

Enter the housing first approach advocated nationally by 100,000 Homes. Their manifesto has four elements:

Housing First:

For years, homeless service providers worked to offer medical and mental health care, addiction counseling, job training and countless other services to people living on the streets. Most homeless people were told they had to earn their way to permanent housing by checking these supplementary boxes.

While the intentions behind this approach were good, the unfortunate result was that very few people ever escaped the streets.

100,000 Homes communities believe this traditional approach is backwards, and the data agrees with them. Countless studies have now shown that we must offer housing first, not last, if we want to help people out of homelessness. An immediate connection to permanent supportive housing can ensure that over 80% of homeless individuals remain housed, even among clients with severe substance abuse and mental health conditions. (read more)

Know Who’s Out There:

Person-specific data is the key to ending homelessness for our most vulnerable (and often anonymous) homeless neighbors.

100,000 Homes communities identify their homeless neighbors by name through an event called a Registry Week, the organizing backbone of the 100,000 Homes Campaign. The Registry Week process is based on a simple idea: communities should work to identify their most vulnerable or at-risk homeless residents and prioritize them for permanent housing. Medical research published in highly regarded, peer-reviewed journals highlights several health and social conditions that make people more likely to die on the streets. We’ve created a survey tool, the Vulnerability Index, that screens for those conditions and helps communities identify the most vulnerable people in their midst.

After an extensive volunteer training, Registry Week volunteers comb the streets of their communities block by block to ask as many people as possible to complete the Vulnerability Index questionnaire. This process occurs early in the morning, usually between the hours of 4 and 7 a.m. to ensure that those surveyed are among the unsheltered homeless population. Unsheltered individuals and families tend to reflect those who are not seeking or engaging with local service systems independently, and thus, those who are most likely to remain unhoused without proactive assistance. (read more)

Track Your Progress:

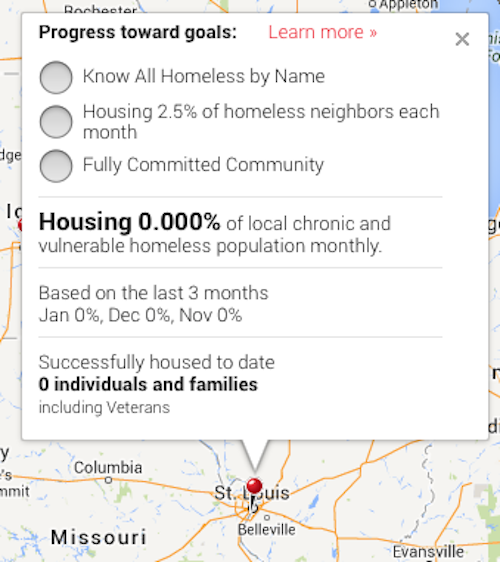

Solving a problem is impossible without a broad-based team and a reliable way of measuring success. Without regular performance data, we have no way of knowing whether or not the methods that communities are employing to end homelessness are working. That’s why 100,000 Homes communities commit to reporting their housing progress monthly and measuring that performance against clear and carefully determined benchmarks.

Each month, local advocates report the total number of people they have housed to the 100,000 Homes data team which uses that information to prepare detailed, individually tailored performance reports for each community enrolled in the Campaign. These reports outline a community’s progress toward its goal of ending homelessness and compare its efforts to the performance of similarly sized and resourced communities around the country.

When communities report consistently for three months in a row, they are placed on the 100,000 Homes Fully Committed List, a list regularly shared with national funders and media representatives in an effort to highly communities who are committed to using data to improve performance. (read more)

Improve Local Systems:

In most cases, the solution to homelessness is apparent– it’s implementing that solution that often proves challenging. This is because most communities have no clear, intentionally developed process for moving homeless people from the streets to permanent housing quickly and efficiently. Typically, different local agencies and organizations own different pieces of the housing process and rarely communicate with one another. These various groups require redundant forms, applications, and interview steps and often fail to process these requirements in a regular or timely way. As a result, it often takes more than a year to move a single individual from homelessness to a home, even with sustainable funding in place.

100,000 Homes communities are committed to pulling together their multiple overlapping service systems into a single, well-oiled housing placement machine capable of moving homeless individuals into permanent housing in as little time as possible. By applying process improvement techniques drawn from industry and the private sector to local housing and human service work, many communities have been able to dramatically reduce the amount of time required to house a single homeless person by as much as 80 percent. (read more)

St. Louis is listed as a community on the organization website but clicking on the dot on the map is disappointing:

I emailed St. Louis’ director of human services William Siedhoff who replied;

“St. Louis might be listed as a community as part of the 100k effort but we have never been a participant in this program and, to my knowledge, none of the surrounding counties are involved either. Therefore, there would be no reporting of data on people being housed in the St. Louis region to this program.”

TAMPA — In 2002, local leaders adopted a 10-year plan to end homelessness in Hillsborough County based on the “housing first” philosophy sweeping the nation. In 2005, the city of St. Louis adopted a similar plan.

Nine years later, St. Louis’ plan has lowered its homeless population by more than 30 percent.

Hillsborough’s plan was never carried out. (read more — highly recommended)

The poll question last week was on homelessness, here are the results:

Q: Do you support giving the chronically homeless apartments?

- Yes, it’s likely cheaper 36 [29.27%]

- Yes, but only after completing work/treatment programs 30 [24.39%]

- Maybe, I need to learn more 29 [23.58%]

- No, they need to work like the rest of society 24 [19.51%]

- Unsure/No Opinion 4 [3.25%]

The 24 who said no are probably the same ones who complain the loudest about the homeless, lots of talk but no actual solutions. Likewise the 30 who said only after completing programs need to understand how housing improves the success rate. Without housing social workers have less success helping these individuals.

The government and public are spending billions annually already, the question is how effective are we? There’s evidence to support the idea that getting the chronic homeless off the streets first lessons the burden on the community and has a greater chance of helping the individuals long term.

— Steve Patterson

So, your poll is really just a vehicle to devalue anyone’s opinion that doesn’t fit your agenda?

I’m one of those no votes, and I agree with many of the observations about St. Louis in the Tampa article – we’re relying on massive amounts of federal money to fund our efforts and our efforts are being negated because adjoining communities are doing little or nothing to address their homeless issues, short of shipping their “problems” into the city.

My no vote is also not a black-and-white response. I support helping people who are facing challenges beyond their own control, especially short-term ones – losing a job, getting divorced, developing mental illness, including PTSD – but I have little sympathy for people who make poor life choices – addiction from drug abuse, both legal and illegal, never-married single moms with multiple baby daddies, or choosing not to take drugs prescribed to deal with one’s mental illness. Choices have (or should have) consequences. We, as a society, cannot continually bail you out of the jams you, yourself, create. Yes, being homeless, multiple times, and potentially (likely?) dying on the street, is a huge negative consequence. But in the immortal words of one philosopher, “You can’t fix stupid”.

So you want communities, hospitals, etc to continue spending, millions to deal with issues related to the chronic homeless rather than look at less costly solutions that actually improve the lives of fellow humans? Not surprised…

Read what I said, I support spending money on fixing the problem, helping people who can be helped, who have become homeless because of crap life threw at them, not because they made poor choices. If you move from beer to vodka to crack to meth or heroin, supporting your growing addiction through robbing and stealing, I really don’t care if you die on the streets – I have no interest in enabling you or your addictions. If you’re a paranoid schizophrenic who refuses to take your meds, and thus can’t hold a job, yeah life sucks, but why should I put a roof over your head?

We tried warehousing the severely mentally ill in institutions, in sanitariums – it didn’t work. What you’re advocating for isn’t much different, just warehousing them in individual apartments. Unless you have a social worker sharing the apartment 24/7, there will always be “clients” / people with problems who will go back to their old ways absent continuous adult supervision. And as long as this remains something dumped on localities to solve, instead of doing it at the national or state level, I can’t support making St. Louis the mecca for every person in the region who needs the level of services the “worst first” require.

The old facilities for the mentally ill were dismantled in large part because of the promise of the newly developed psychiatric drugs to “cure” these individuals; in hindsight, this was probably somewhat naive and not especially wise due to the disinclination or inability of many of these individuals to rigorously adhere to their medication schedules, as well as a lack of life and job skills in a great many of these cases. I voted “no” in the poll, but only because I don’t have much hope that addicts and the mentally ill are likely to function well in their own apartments without some type of supervision. If supervison were available, however, I would probably tend to support something along these lines. The current system of dealing with the dysfunctional mentally ill has been a failure IMO, with many of these people winding up being warehoused in prisons. I think society probably has some minimum sort of duty to help the mentally ill, and I don’t think that is really being fulfilled as things currently stand.

Supervision comes in the form of social workers being able to check in on them daily.

The creation of St. Louis’s suburbs left no place for those who don’t fit. Don’t expect to be welcomed in any of the communities surrounding the city if you are poor, elderly, or homeless. With no where else to go the suburbs have found the solution to their unpleasant problems by forcing people unto the street of the city where they become someone’s else’s problem. The homeless problem in America has to do more with the severing of traditional family support units than anything else. Nothing the city can provide will ever change this and its time that our surrounding community sown up to what is their problem and start working toward a solution, rather than expect the city to take care of it.