Reading: Convention Center Follies: Politics, Power, and Public Investment in American Cities by Heywood T. Sanders

Friday I listed five books about St. Louis to consider as gifts. Today’s book, a massive volume, isn’t about St. Louis. Well, not entirely. Chapter 8, titled “St. Louis: Protection from Erosion”, is the story of our own convention center folly. From the publisher:

American cities have experienced a remarkable surge in convention center development over the last two decades, with exhibit hall space growing from 40 million square feet in 1990 to 70 million in 2011—an increase of almost 75 percent. Proponents of these projects promised new jobs, new private development, and new tax revenues. Yet even as cities from Boston and Orlando to Phoenix and Seattle have invested in more convention center space, the return on that investment has proven limited and elusive. Why, then, do cities keep building them?

Written by one of the nation’s foremost urban development experts, Convention Center Follies exposes the forces behind convention center development and the revolution in local government finance that has privileged convention centers over alternative public investments. Through wide-ranging examples from cities across the country as well as in-depth case studies of Chicago, Atlanta, and St. Louis, Heywood T. Sanders examines the genesis of center projects, the dealmaking, and the circular logic of convention center development. Using a robust set of archival resources—including internal minutes of business consultants and the personal papers of big city mayors—Sanders offers a systematic analysis of the consultant forecasts and promises that have sustained center development and the ways those forecasts have been manipulated and proven false. This record reveals that business leaders sought not community-wide economic benefit or growth but, rather, to reshape land values and development opportunities in the downtown core.

A probing look at a so-called economic panacea, Convention Center Follies dissects the inner workings of America’s convention center boom and provides valuable lessons in urban government, local business growth, and civic redevelopment.

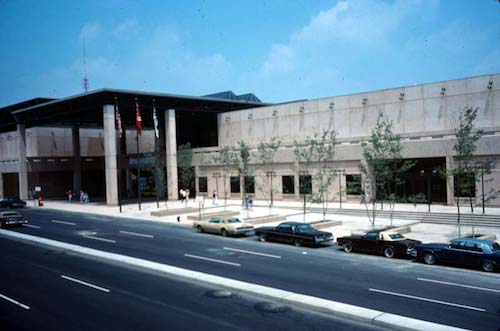

Reading the background on how the Cervantes Convention Center came to be is fascinating! There were competing proposals to locate a convention center elsewhere, including near Union Station.

Other chapters deal with other aspects, for example:

- Paying for the box (Ch2)

- Promises and Realities (Ch3)

- They Will Come…and Spend (Ch4)

If you want a complete overview of convention centers this is the book for you.

— Steve Patterson

There is a tendency, in government, to say that if something, anything, is successful, somewhere else, that it will be equally, or more, successful, if replicated, “here”. It doesn’t matter if it’s a convention center, an aquarium, a museum, a street converted to a pedestrian mall, a highway bypass, a streetcar line, an enclosed mall or a new Walmart, doing the same thing is no guarantee of success. Life is complex. Many issues, within one’s control and not, factor into success or failure, long-term sustainability or being just a “flash in the pan”. There’s also a tendency, among elected officials, to be overly-optomistic when it comes to spending other people’s money (our tax dollars), since they likely won’t “take the hit” if there is a failure, and they can always point at the short-term boost to the local construction industry.

The challenge with convention centers is that no two conventions are the same and there are relatively few really big ones, ones that need hundreds of thousands (or millions) of square feet of exhibition space and thousands of hotel rooms. Most conventions are far smaller. Five cities can handle more than 3 million square feet, seven can handle between 2 and 3 million, fifteen can handles between 1 and 2 million, and everyone else is chasing those conventions that need less than a million: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_convention_centers_in_the_United_States . . St Louis can handle a half million square feet: http://www.cvent.com/rfp/st-louis-hotels/america-s-center/venue-e3ce2326ade2470696a9854fc3ad122f.aspx

The real analysis needs to include both the cost of construction and the actual usage and revenue generated. It would be interesting to compare America’s Center (500,000 sq. ft.) to St. Charles (http://www.stcharlesconventioncenter.com/ . . 35,000 sq. ft.) and Gateway Center in Colinsville (http://www.gatewaycenter.com/ . . 50,000 sq. ft.). This isn’t about ego, this is about revenues. Is it better to have 400 or 600 events a year, and have the facility used on a regular basis? Or is it better to host a few relatively big shows a year, and have the facility be little used 200+ days a year? (The list of upcoming events for Americas’s Center is pretty sparse: http://explorestlouis.com/meetings-conventions/americas-center/edward-jones-dome/upcoming-public-events/ . . )

^ those are public events you linked to and don’t include private functions…. I suspect the center handles 400-600 smaller “local” events a year. they’re just not publc.

You’re right the numbers are “apples and oranges”, but they’re the only ones I could find. My point is that we have a facility that is 10X+ the size of the other two (and likely built at 10X+ the cost), so we should be expecting the 10X the revenue, if not 10X the use. If “the center handles 400-600 smaller “local” events a year”, it’s still being used far less intensively (and profitably) than the other two. As the book documents, bigger is not necessarily better . . . .

You can find out more about CVB results in the 2014 report accessible here….

http://explorestlouis.com/st-louis-cvc/

I believe the CVB is seeking to expand its ballroom and a possible mixed-use garage but I’m not too sure what else it may have in mind…. I suppose the eventual outcome of the Rams situation will impact its future.