Cleveland’s Healthline Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), Part 4

This is my final part on Cleveland’s Healthline Bus Rapid Transit (BRT). However, donations to offset the cost are still accepted here.

Earlier posts:

One of the articles that got me seriously looking at BRT was from Forbes in September 2013: Bus Rapid Transit Spurs Development Better Than Light Rail Or Streetcars: Study. Two parts stood out:

“Per dollar of transit investment, and under similar conditions, BRT can leverage more (development) investment than LRT or streetcars.”

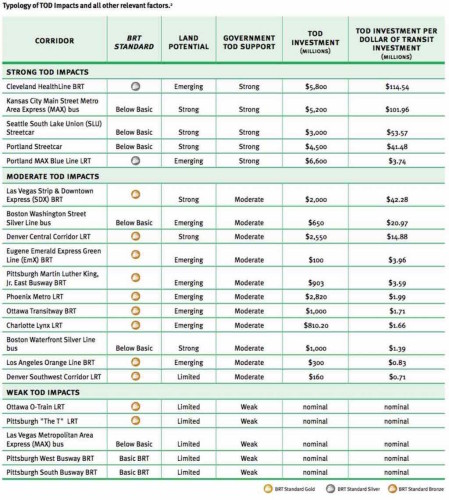

For example, Cleveland’s Healthline, a BRT project completed on Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue in 2008, has generated $5.8 billion in development —$114 for each transit dollar invested. Portland’s Blue Line, a light rail project completed in 1986, generated $3.74 per dollar invested.

and…

The U.S. has seven authentic BRT lines in Cleveland, Las Vegas, Los Angeles, Eugene Ore., and several in Pittsburgh. None achieve the internationally recognized “gold standard” of BRT like Bogota’s TransMilenio line. But one planned for Chicago’s Ashland Avenue might.

“There’s no gold standard BRT in the U.S. yet,” Weinstock said, “but if we continue with the Ashland project on the current trajectory, Ashland could be the first gold in the U.S.”

I’ll address Chicago’s Ashland Ave in a future post. BRT — more development return than LRT or streetcars?

Long-time readers know I love rail — especially streetcars. Public transit was often about real estate development, to get people to a new project, developers would build a streetcar line to get them there. Cities would lease part of the public right-of-way (PROW) so they could operate. Cities, including St. Louis, would have multiple private companies providing public transit. Eventually cities would increase the fees for the track & overhead wires in the PROW or even require the operators to repave roads where they operated. This quickly made streetcar operations unprofitable. One solution, of course, was to abandon the track and use rubber tire vehicles — the bus.

Eventually governments bought up all the private systems — remaining streetcar lines and those that had been converted to bus. Remember, their origin was rooted in the development of real estate. With land developed these lines became strictly about moving people to/from. We need to retuning to the days of the connection between transit and development!

Which brings me back to Cleveland’s Healthline, it had an amazing $114.54 dollars of development for every dollar spent on the BRT line. Below is page 9 from More Development for Your Transit Dollar: An Analysis of 21 North American Transit Corridors.

As you can see from the BRT, LRT, and streetcar limes above the return on investment is all over the board. In the top section (Strong TOD Impacts) we see the LRT cost more than the BRT or streetcar lines, but had significantly less development. A return of $3,74 on every dollar looks good until compared to $41.68 or more. Kansas City’s MAX bus line doesn’t even meet the basics to be BRT — yet it has had a return of $101.96 per dollar!

The report begins talking about the Metro subway system in Washington D.C. — a long & costly undertaking:

A growing number of US cities are finding, however, that metro or subway systems are simply too expensive and take too long to implement to effect significant changes in ongoing trends toward suburban sprawl. As such, cities are turning to lower-cost mass transit options such as LRT, BRT, and streetcars. These systems, which frequently use surface streets, are much less expensive and can be built more quickly than heavy-rail subways or metro systems. Over the past decade, some evidence has emerged that some LRT systems in the US have had positive development impacts. Outside of the US, in cities like Curitiba, Brazil, and Guangzhou, China, there is copious evidence that BRT systems have successfully stimulated development. Curitiba’s early silver-standard BRT corridors, completed in the 1970s, were developed together with a master plan that concentrated development along them. The population growth along the corridor rate was 98% between 1980 and 1985, compared to an average citywide population growth rate of only 9.5%. However, because bronze-, silver-, or gold-standard BRT is still relatively new to the US, evidence of the impact of good-quality BRT on domestic development is only now beginning to emerge and has been largely undocumented. (p14)

A detailed look at the Corridors with Strong TOD Impacts begins on page 110:

The analysis shows that all of the corridors in the Strong TOD Impacts category had Strong government TOD support and either Emerging or Strong land potential.

The only two transit corridors in our study that rate above bronze — the Cleveland HealthLine BRT and the Blue Line LRT — both fell into the Strong TOD Impacts category and were in Emerging

land markets. The Blue Line LRT leveraged $6.6 billion in new TOD investments, and the Cleveland HealthLine BRT leveraged $5.8 billion, making them the two most successful transit investments in the country from a TOD perspective. Portland achieved this over a much longer time period and in a stronger economy than Cleveland did.In the Strong TOD Impacts category, three corridors with below-basic-quality transit had Strong land development potential and Strong government TOD support: the Portland Streetcar, the Seattle SLU Streetcar, and the Kansas City Main Street MAX.

In each of these cases, local developers and development authorities did not feel that the transit investment was all that critical to the TOD impacts. Thus, we can conclude that if the land market is strong enough, and the government TOD efforts strong enough, a below-basic transit investment might suffice; but a higher-quality transit investment could have even greater impacts.

Not all of the investment along Cleveland’s Healthline is urban. We visited this CVS — built right after the line opened. The building is set back behind a fenced parking lot.

As I noted previously. a lot of the new development was on college & hospital campuses — it would’ve happened anyway — but it faces the street rather than looking internal (like SLU, BJC, etc).

I’ve got to read the full report a few more times so absorb it all — while recognizing it was written with a pro-BRT viewpoint.

Any TOD effort is most successful when land-use planning and urban development efforts are concentrated around a high-quality mass transit corridor that serves land with inherent development potential. Assistance from regional and city-level agencies, community development corporations, and local stakeholders can help create more targeted policies to direct development to such transit corridors. Local foundations can be critical to the process of funding redevelopment and providing capital and equity for projects. Local NGOs, which can communicate the projects to the public to help broaden support, are also important.

Although cities in the US are still far from fully transforming their declined urban neighborhoods into high-quality, mixed-use urban developments, they are well on their way. Gold-, silver-, or bronze-standard BRT, when combined with institutional, financial, and planning support for TOD, is proving to be a cost-effective way of rebuilding our cities into more livable, transit-oriented communities.

Regardless of their bias, the above is true — we’ve invested hundreds of millions in light rail and have little TOD to show for it because of poor land-use planning.

Like streetcars & LRT, I think BRT is a great option to consider in the St. Louis region, We can argue about the mode, but we need to take action to have land-use planning that will strongly support transit-oriented development!

— Steve Patterson

You note “We need to [return] to the days of the connection between transit and development!”, and I have no problem with the fundamental statement. What you glossed over, however, is that PRIVATE developers created the original streetcar systems, with their own dollars, while most of the streetcar and BRT systems of today rely primarily (or exclusively) on PUBLIC funding for their construction and operation. If Vatterott, for example, wanted to construct a streetcar line to serve one of their new subdivisions AND pay the local governments for the use of their rights-of-way, that would be a completely different scenario from the Loop Trolley, where more than $50 million in public funding is being used to support the development aspirations of a few dozen property owners!

For your closing statement, you assert that “We can argue about the mode, but we need to take action to have land-use planning that will strongly support transit-oriented development!” I agree, up to a point. We also need to create a market for all of these wonderful plans and investments. TOD isn’t happening at most Metrolink stops because the planning is inadequate; it’s not happening because nobody with the financial resources to build TOD has any interest in building TOD! These developers HAVE “considered” the benefits of mass transit and have yet to find a reason be very inclusive of local transit or local transit riders. Planning won’t change that; financial success (more profits) WILL!

The market exists, other regions have taken full advantage of it rather than set policies to squash it.

When Metro was crested by Missouri & Illinois in 1949 the name was Bi-State Development! http://www.metrostlouis.org/About/History.aspx

Bi-State was not created as a transit agency – that got dumped into their laps to figure out . . . if the market existed, here, development would be happening, with or without “planning”. . .

The problem is that the local governments used the private streetcar systems as piggybanks, regulating their fares while taxing them. This is what drove them bankrupt in the first place.

You might suggest that the local governments should have left them alone… but that’s what they did with the big steam railroads, and they became holy terrors, unaccountable private monopolies with uncaring billionaires saying “the public be damned!”

It is unequivocally best for the transportation to be owned by the public sector.

It’s “best” only if there’s a consensus to adequately fund public transit, which, unfortunately, does not seem to be the case in the St. Louis region . . .

Another form of BRT: http://www.rtd-denver.com/flatiron-flyer.shtml

The route matters more than the difference between bus and rail.

Euclid Avenue was the correct route in Cleveland. Had this route been rail, there would have been between 10% more and 25% more riders, and correspondingly more development.

By contrast, South Lake Union was a deeply questionable route in Seattle to start with. Ottawa’s original O-Train is a very minor route. And Boston’s “Silver Line” is an appallingly terrible route.

Pittsburghers might be surprised to hear they are economically depressed… it is enjoying better economic growth than our own region and while you’re correct it is static in population growth overall, like St. Louis City it has some hot spots — The Strip is booming and East Liberty is seeing substantial progress. Downtown is much more vibrant than ours.