Opinion: Razing Vacant Buildings A Short-Term Strategy With Negative Long-Term Consequences

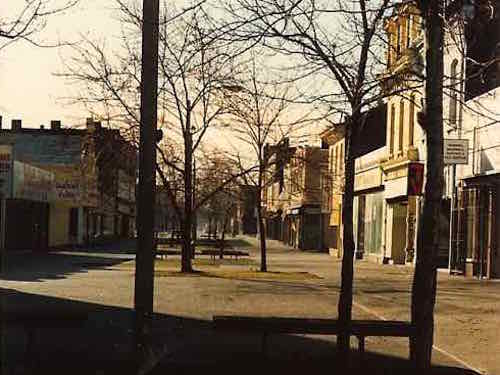

Razing buildings might seem like the answer, but the unintended consequences shouldn’t be overlooked.Sure, no vacant building but then you’ve got a vacant lot unlikely to be developed. Dumping, high weeds, etc are all nuisances that can happen at vacant lots. While rehabbing an old building is more expensice than building new, it’s also more likely than new infill construction — especially in marginal (low demand) neighborhoods.

Obviously St. Louis doesn’t have the population it had in 1950 — but that was a time of severe overcrowding. The number of housing units didn’t meet the need. As, mostly Northside, neighborhoods continue to empty out it becomes harder and harder to support these areas. What does that mean? Sparsely populated areas with few remaining structures should likely be cut off so limited resources can be focused on more populated areas. However, doing so will have a huge impact on low-income/minority neighborhoods.

This was part of the 1970s Team Four plan, still widely criticized today. From 2014:

Some corners of St. Louis still have hard feelings over the so-called “Team Four” plan of the early 1970s, which studied that approach. And a similar effort to “right-size” Detroit was scuttled a few years ago amid sharp resident opposition. (Post-Dispatch)

You can’t tear down buildings indiscriminately all over the city and not expect consequences.

When I travel throughout neighborhoods I think about many buildings that people, including the Alderman, wanted razed. Many of these are now rehabbed and occupied. Holding onto these structures until a plan could be put together helps bring a positive vibe to struggling neighborhoods.

As mentioned above, people were upset about “right-sizing” Detroit. also known as urban triage. From 2009, early on in the effort:

Today, though, more and more people in leadership positions, including Mayor Dave Bing, are starting to acknowledge the need to stop fantasizing about growth and plan for more shrinkage. Growth is as American an ideal as the capitalistic enterprises that fuel it. So by itself, this admission is a step forward.

It’s way overdue. Detroit has been shrinking for 50 years. The city has lost more than half of the 2 million people it had in the early 1950s, but it remains 138 square miles. Experts estimate that about 40 square miles are empty, and Bing has said that only about half the city’s land is being used productively.

The next steps are complicated and largely uncharted. Moving residents into more densely populated districts has legal and moral implications; it must be done with care and the input of those who would be moved. And what do you do with the empty space? The city is already dotted with big vegetable gardens, and one entrepreneur has proposed starting a large commercial farm. Some people advocate bike paths, greenways, and other recreation areas. Surrounded by fresh water, and buffeted by nature reasserting itself on land where factories used to be, Detroit could someday be the greenest, most livable urban area in the country. A city can dream, can’t it? (Newsweek)

You can’t want vacant buildings razed and not expect the least populated areas to be written off. Don’t want to be written off? Stabilize vacant buildings and work to get them rehabbed.

Just over half of those who voted in the recent non-scientific Sunday Poll also don’t think razing buildings will help.

Q: Agree or disagree: Tearing down vacant buildings more quickly will help St Louis.

- Strongly agree 8 [18.18%]

- Agree 3 [6.82%]

- Somewhat agree 5 [11.36%]

- Neither agree or disagree 4 [9.09%]

- Somewhat disagree 3 [6.82%]

- Disagree 7 [15.91%]

- Strongly disagree 13 [29.55%]

- Unsure/No Answer 1 [2.27%]

Obviously, there isn’t consensus on this issue.

We need to have a serious community discussion about the future of this city. What’s our plan — controlled shrinkage or aggressive infill? Probably both is the best way to proceed. This reminds me about an old planning joke about a city tearing down enough downtown buildings for parking, only then realizing there wasn’t enough downtown left to attract anyone.

— Steve Patterson