Readers Mixed On Latest Blight Removal Effort

Blight was in the news last week, and was the topic of the recent non-scientific Sunday Poll.

Before I get to the poll results, let’s talk about blight.

We have obsolete and blighted districts because our interest has always been centered in the newest and latest houses and subdivisions in areas of new development. As home owners have moved to successive outlying neighborhoods the earlier homes have gradually been allowed to deteriorate. No matter how great the extent of disintegration these old homes are seldom adequately repaired and are rarely torn down. This is no way to build a sound city.

The above quote isn’t from a press release about the new effort, it’s from St. Louis’ Comprehensive Plan — from 1947!

Combating blight is nothing new, but what is blight? In 1947 part of their definition was the number of housing units built prior to 1900 (82,000), number of units with an outdoor privy/outhouse (33,000), and the number of units where families shared a toilet (25,000). Today we do still have units built before 1900, but I doubt a single housing unit in the city lacks a private bathroom.

Yet blight remains, in different forms. Dictionary.com defines blight as:

the state or result of being blighted or deteriorated; dilapidation; decay: urban blight.

St. Louis certainly has lots of deteriorated, dilapidated housing stock. For every home lovingly restored there’s probably 10 in various states of disrepair. St. Louis has struggled with this for generations. The latest effort because it involves two wealthy individuals trying to leverage their fortunes:

Tech billionaire Jack Dorsey, a St. Louis native and co-founder and CEO of both Square Inc. and Twitter, along with Detroit native Bill Pulte, whose grandfather founded national homebuilder Pulte Homes, were paying for the demolitions — $500,000 for a pilot program to completely clear more than 130 lots in a four-block area of the northwest St. Louis neighborhood hard hit by abandonment and vacancy.

“St. Louis is a lot easier to solve,” said Pulte, who several years ago launched the Blight Authority, a similar initiative in the Detroit area. “This problem can be solved. This problem can be solved in less than 15 years…. This is just about willpower at the government and private sector level.”

So why not renovated, rather than raze? Good question. The answer is complicated, but “willpower” is an important factor. If we look at Old North St. Louis many buildings in very poor condition were stabilized for many years until they could be renovated. It was a huge effort that paid off…eventually. The neighborhood has seen considerable new infill since, from Habitat for Humanity houses to a trendy shipping container house. Very different than when I lived in the neighborhood, 1991-1994. It helps the neighborhood is on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Wells Goodfellow neighborhood is very different from Old North. It’s also old, but at least a generation newer than Old North.

Wells/Goodfellow is part of an historic section known as Arlington, which takes its name from John W. Burd’s Arlington Grove subdivision of 1868. A memorable disaster in the history of the Arlington area occurred in October 1916, when the Christian Brothers College building at North Kingshighway and Easton Avenue (now Martin Luther King Drive) was destroyed by fire, one of the worst in the City’s history, taking 10 lives.

The area received its name from John W. Burd’s Arlington Grove subdivision of 1868. More subdivisions were built in the mid-1880s, with residential construction continuing until 1910. By the mid-1920s, the last of the residential subdivisions were opened. (City of St. Louis)

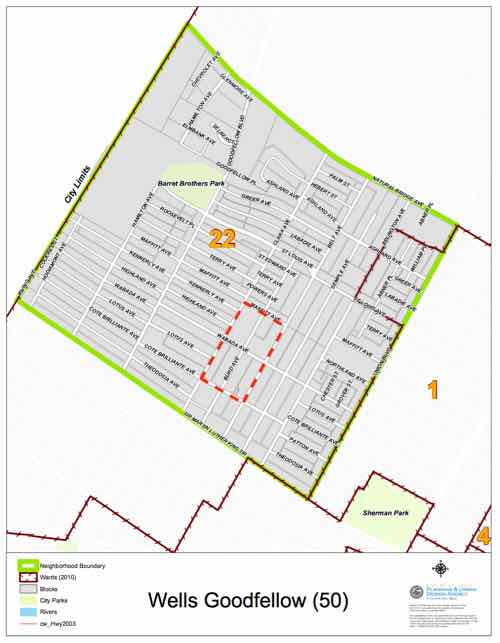

The location is on the far west edge of the city:

Wells Goodfellow general boundaries are defined as Natural Bridge Ave. on the North, southward to Union Blvd. on the East, westward to Dr. Martin Luther King Drive on the South, northward to the City limits on the West to Natural Bridge Ave. (City of St. Louis)

The housing stock is a mix of brick structures like we see in many neighborhoods, and wood frame structures that are becoming increasingly rare.

I’m a huge fan of old wood-frame buildings, especially large homes from St. Louis’ heyday. The home above was a pile of rubble by August 2017 but not cleaned up until this month.

These large frame homes are the exception for the neighborhood, most housing is smaller and modest.

The two that were razed were in bad shape two years ago. 1910 Clara Ave was built in 1908, was just over a thousand square feet in size. 1906 Clara Ave was built a year earlier, was just under 900 square feet. The two remaining houses are similar vintage and size.

I’m sure the owner-occupant of one of the remaining houses is relieved to have the dilapidated neighboring structure gone. Both of the razed houses might have been technically feasible to renovate, but the economics just don’t add up in Wells Goodfellow.

There is one neighborhood in St. Louis where modest frame & masonry shotgun houses are well maintained, and often renovated. The Hill — the Italian neighborhood.

When these aren’t renovated you’ll see a larger home built where 2-3 once existed.

The Hill neighborhood is of similar vintage and the housing stock was originally very similar — modest worker housing of frame or brick construction. One has had continuous investment, the other large scale abandonment. In Wells Goodfellow few buildings are listed for sale in the MLS. Those that are listed cost less than the average new car. Hell, less than many good used cars. Other city neighborhoods with this type of housing the unfortunate reality is closer to Wells Goodfellow than The Hill.

So when an owner-occupant dies their family sells the house to the only buyer, likely an absentee landlord. At these prices they can recoup their initial investment in less than 5 years. The landlord rents it for as long as they can, then walk away.

This brings us back to the issue raised in the 1947 plan:

We spend $4,000,000 general tax funds annually to maintain our obsolete areas. (This sum represents the difference in cost of governmental service and tax collections annually in these areas.)

In 1947 we had overcrowding and hadn’t reached our peak population. Since then we’ve lost nearly 2/3 of our population. Do we write off this neighborhood, or keep investing like the successful Arlington Grove housing immediacy to the south of this blight elimination zone?

In 1975, consultants from Team Four Inc. advised St. Louis planners to pursue a strategy of neighborhood triage: ‘‘conservation’’ for areas in good health, ‘‘redevelopment’’ for areas just starting to decline, and ‘‘depletion’’ for areas already in severe distress. The firm’s recommended strategy reflected the latest thinking among urban planners, but it provoked outrage among residents of the city’s predominantly black North Side, who read ‘‘depletion’’ as a promise of benign neglect. (The Trap of Triage: Lessons from the ‘‘Team Four Plan’’)

While you ponder the implications of not rebuilding the neighborhood, let me share more of my photos from visits this weekend.

I get these mass demolitions, if I lived in Wells Goodfellow the decay would be stifling. I also think the mass demolitions will send the message not to invest in the housing, because the neighborhood is disposable.

Here are the non-scientific results of the Sunday Poll:

Q: Agree or disagree: 15 years from now these cleared blocks in the Wells-Goodfellow neighborhood will be an asset, lifting the rest of the neighborhood.

- Strongly agree: 3 [9.68%]

- Agree: 7 [22.58%]

- Somewhat agree: 2 [6.45%]

- Neither agree or disagree: 2 [6.45%]

- Somewhat disagree: 4 [12.9%]

- Disagree: 4 [12.9%]

- Strongly disagree: 7 [22.58%]

- Unsure/No Answer: 2 [6.45%]

It’s very hard to think the area of cleared lots will be an asset in 15 years, a lot depends on what happens next.

— Steve Patterson