Mill Creek Valley Neighborhood Was Less Important Than An Expressway

Since his arrival in St. Louis in 1915 Harland Bartholomew, a civil engineer by training, wanted cars to be able to move with greater ease. He relentlessly argued in favor of destroying the city’s rich urban fabric, street grid, in order to save the city from urban decay. He was young and charismatic, convincing generations of St. Louisans his way was the only way.

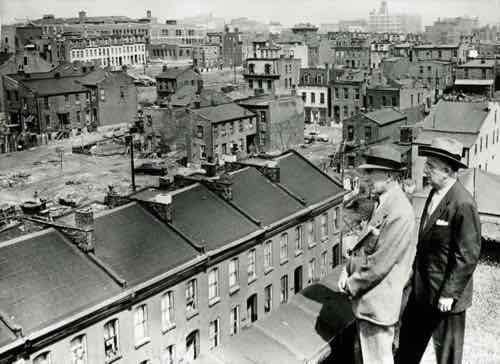

Lawton was an east-west street between Pine & Laclede, the above would’ve been just west of Compton Ave.

The chaos created by decades of Bartholomew’s projects created so much instability — far worse than than anything natural decay was creating. Widening streets and building new expressways was part of Bartholomew’s vision. It was costly but necessary, he argued.

In 1936 the first phase of a new expressway opened between Kingshighway and Skinner, cutting through the south edge of Forest Park. This was two decades before the creation of the Interstate Highway System! A year later another section opened between Vandeventer and Kingshighway. Many could see it reaching downtown eventually.

Highway planners in those days drew lines on map to connect the dots, sometimes meandering a bit here and there to avoid an important business, like Anheuser-Busch brewery in the case of what is now known as I-55. Otherwise their lines indiscriminately cut through neighborhood after neighborhood.

As these highways were going through the oldest parts of the city they were also going through the poorest neighborhoods. Older “slum” areas were viewed as obsolete anyway — two birds, one stone. By the 1959s Mill Creek Valley, bounded by Union Station on the east, railroad tracks on the south, Grand on the west, and Olive on the north, was a dense neighborhood.

Because of segregation, it was self-contained. Yes, it was deteriorated and most residences lacked running water and indoor bathrooms. The buildings were nearly a century old. Numerous generations of new immigrants had begun their lives in America in this neighborhood, the last was southern blacks trying to escape Jim Crow laws while looking for work.

To an outsider it likely seemed like a horrible place, but to residents it was home. They had connections with each other, lasting institutions, etc. Poor neighborhoods all over the city were the same way, they didn’t look like much but it was the ties among the residents that was more important than the street grid or buildings. But take away the buildings and the streets and those strong ties among thousands quickly disappear. It’s an unnatural disaster.

During the 1950s, Saint Louis found itself in a fervor over urban deterioration and renewal. Following Mayor Joseph Darst’s 1953 slum clearance in the Chestnut Valley area, Mayor Raymond Tucker initiated a similar project in the adjacent Mill Creek Valley. This area – bounded by 20th Street, Grand Avenue, Olive Street and Scott Avenue – housed a large African-American population, and was at one time the home to such famous African-Americans as Scott Joplin and Josephine Baker. At the start of the 1950s, the Mill Creek Valley house 20,000 inhabitants (95% African-American) and included over 800 businesses and institutions. Everything the residents needed – from grocery, clothing and hardware stores to restaurants, schools and churches – was within walking distance of their homes. The area was also home to the prominent African-American newspaper, The St. Louis Argus. However, many of these residences and institutions were considered unsanitary and in need of repair.

In 1951, Missouri Governor Forrest Smith signed the Municipal Land Clearance for Redevelopment Law, which brought state aid to the urban renewal efforts of Missouri’s cities. The law also created the St. Louis Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority, whose job it was to oversee urban renewal in Saint Louis and manage its funding. Under the 1954 Federal Housing Act – which provided federal aid for renewal projects – and the passage in 1955 of a $110 million bond issue, Mayor Tucker and the City of St. Louis began the clearance and demolition of slums in Mill Creek Valley. The most of the bond revenue went towards construction of new expressways, some of which cut through parts of Mill Creek. Roughly $10 million was utilized for slum clearance. The clearance of the area would involve the relocation of many residents and businesses; most residents would never return and many businesses would cease operations. Acquisition of buildings, like the Pine Street Hotel and the Peoples Finance Building, began in August of 1958, with actual demolition starting the following year. Redevelopment of the area would include new residential, commercial and industrial zones, with the majority of land going towards new industry. Certain industries that met zoning requirements, like Sealtest Foods, would not face demolition and were allowed to stay. Redevelopment of the entire area was scheduled for completion in 1968. (UMSL)

The city systematically created disasters all over the place. The pace must’ve been overwhelming to many at the time. Hundreds of thousands were uprooted. It’s a formula for the population losses that have happened since.

Mill Creek Valley was at the wrong place at the wrong time. By 1950 Bartholomew was in Washington D.C., but his raze & replace attitude continued. Other options weren’t considered, especially when the land is needed for an expressway to connect downtown to affluent western suburbs as the wealthy continued moving westward along the central corridor.

Here are the results of the recent non-scientific Sunday Poll:

Q: Agree or disagree: Mill Creek Valley was a slum (no indoor plumbing, etc); leveling it was the only option

- Strongly agree: 0 [0%]

- Agree: 1 [5.56%]

- Somewhat agree: 1 [5.56%]

- Neither agree or disagree: 0 [0%]

- Somewhat disagree: 1 [5.56%]

- Disagree: 4 [22.22%]

- Strongly disagree: 10 [55.56%]

- Unsure/No Answer: 1 [5.56%]

Again, demolition was the only option considered. One, this generation didn’t see any value in the narrow & compact street grid or in 19th century flats. The other is they really wanted the land for a highway. As a bonus white folks could now drive on Olive & Market streets between the Central West End and downtown without having to go through a black neighborhood.

With so much uprooting & demolition it is amazing we have any residents or buildings left. The leaders at the time just couldn’t/didn’t see the tremendously negative consequences their actions would have on the city & region for decades to come. After all, everything they were doing was in an effort to save the city from decay.

— Steve Patterson