Corrections to the Mill Creek Valley Narrative

I feel the need to correct the record regarding Mill Creek Valley, to counter the false information being repeated.

Though St. Louis was founded in 1764 it wasn’t incorporated until 1823. At that time “the city limits were expanded west to Seventh Street and north and south by approximately 5 blocks each.” (Wikipedia) In 1861 the limits were expanded west to Grand, but streets and development had already gone further west. The land for Forest Park was purchased in 1875 — it was located in St. Louis County, not within the city limits of St. Louis. The current municipal boundaries were set in the 1876 divorce from St. Louis County, they were rural at the time.

There was no singular cohesive Mill Creek Valley neighborhood. The large rectangular area (454 acres) the city demolished for “urban renewal”, bounded by 20th St, creek/railroad, Grand Ave, Olive St., included many communities, businesses, homes, etc. was built over many decades — neighborhoods plural. Our modern perception of neighborhoods having distinct edges didn’t exist then, your neighborhood was where you lived. People who lived between 20th & Jefferson didn’t see their area belonging to the newer area west of Compton. The fact this large area ended up being grouped together and labeled by the city as a redevelopment area doesn’t make it a single neighborhood.

Commonly the word “downtown” refers to a city’s central business district (CBD). The size/location of “downtown St. Louis ” varies depending upon who you ask. To some anything east of I-270 is downtown. When St. Louis Union Station reopened at its new facility on September 1, 1894 it was considered far west of the CBD/downtown. The original station, on the east side of 12th (now Tucker), opened on June 1, 1875.

Thus, the Mill Creek redevelopment area wasn’t the heart of downtown. Not even close. Starting at 20th and going west, it wasn’t the oldest part of the city either. The stately row houses in this area were significantly newer and nicer than the tenements east of 10th Street. It was certain old by the 1940s, just not the oldest. It was also dense and lively, with everything within a short walk. Market Street ran down the center of the rectangular redevelopment area and contained the majority of the commercial activity, but corner shops also existed.

Since the city’s founding African-Americans lived in tight pockets throughout the city and St. Louis County. The black population before the Civil War was a very small percentage.

Not all persons of color in St. Louis were slaves, and in fact, as the 19th century progressed, the number of free blacks continued to rise. This can be explained by looking at several factors. Conditions in St. Louis enabled self-purchase. St. Louis’ proximity to Illinois, a state where slavery was supposed to be illegal, allowed a small number of slaves to sue for their freedom in St. Louis courts based on the premise that they had been held as slaves for a period of time in a free state. A very small number were also set free by masters who had come to see slavery as a moral wrong. Former slaves who wished to remain in the State of Missouri as free blacks were supposed to obtain a license from the state.

In addition to the over 1,000 free blacks in St. Louis who owned small businesses, were laborers or worked odd jobs, a certain elite group of African-American St. Louisans styled “the Colored Aristocracy” were large landowners and businesspersons, many descended from some of St. Louis’ earliest residents. Several owned the large barber emporiums, while others owned drayage businesses which moved goods from steamboat to steamboat on the levee. Still others, like Madame Pelagie Rutgers, owned huge tracts of land which they sold at great profit as the city expanded. The “Colored Aristocracy” of St. Louis had its own social season and debutante balls. A member of this social class, Cyprian Clamorgan, wrote a book in 1858 called the Colored Aristocracy of St. Louis, in which he profiled the group. (National Park Service — highly recommended)

Yes, wealthy blacks in the 19th century. They didn’t live in the area we know today as Mill Creek. They lived in The Ville.

During the 1920s, The Ville was home to an elite community that included black professionals, businessmen, entertainers and Annie Malone, one of the country’s first African-American millionaires. One of St. Louis’ most historically significant neighborhoods, The Ville was home to Sumner High School, the first school west of the Mississippi River to provide secondary education for blacks. Some of the school’s best known alumni are Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Famer Chuck Berry, opera diva Grace Bumbry, and tennis great Arthur Ashe. During the 1920s and ‘30s, the neighborhood thrived, as more and more African-American institutions were established, including Harriet Beecher Stowe College and Homer G. Phillips Hospital.

The Ville served as the cradle of African-American culture and nurtured its rich heritage for the black population of St. Louis. Today, the soaring Ville Monument pays tribute to the neighborhood’s achievements and its famous sons and daughters. (Explore St. Louis)

Sumner High School, mentioned above, opened downtown on 11th between Poplar & Spruce in 1875 — the same year as the adjacent first new Union Station mentioned earlier:

Charlton Tandy led protests of the planned siting of Sumner High School in a heavily polluted area in close proximity to a lead works, lumber and tobacco warehouses, and the train station as well as brothels. He said that black students deserved clean and quiet schools the same way white students do. The location went unchanged, and Sumner High opened in 1875, the first high school opened for African Americans west of the Mississippi. The school is named after the well-known abolitionist senator Charles H. Sumner. The high school was established on Eleventh Street in St. Louis between Poplar and Spruce Street, in response to demands to provide educational opportunities, following a requirement that school boards support black education after Republicans passed the “radical” Constitution of 1865 in Missouri that also abolished slavery.

The school was moved in the 1880s because parents complained that their children were walking past the city gallows and morgue on their way to school. The current structure, built in 1908, was designed by architect William B. Ittner. Sumner was the only black public high school in St. Louis City until the opening of Vashon High School in 1927. Famous instructors include Edward Bouchet and Charles H. Turner. Other later black high schools in St. Louis County were Douglass High School (opened in 1925) and Kinloch High School (1936). (Wikipedia)

Sumner High was an 1867 school renamed. Originally it was District School Number Three. Source: 1960 handbook.

Locations:

- 1867, 5th & Lombard

- 10th & Chambers

- 1875, 11th & Spruce — now known as Sumner instead of #3.

- 1896, 15th & Walnut

- 1908 construction on the current location in The Ville neighborhood began

- 1910 classes began, moving from 15th & Walnut.

Wealthy blacks in St. Louis were successful in relocating Sumner t0 their neighborhood, where their homes and businesses were located.

Another well-known institution in The Ville was Homer G. Phillips Hospital.

Between 1910 and 1920, the black population of St. Louis increased by sixty percent, as rural migrants came North in the Great Migration to take industrial jobs, yet the public City Hospital served only whites, and had no facilities for black patients or staff. A group of black community leaders persuaded the city in 1919 to purchase a 177-bed hospital (formerly owned by Barnes Medical College) at Garrison and Lawton avenues to serve African Americans. This hospital, denoted City Hospital #2, was inadequate to the needs of the more than 70,000 black St. Louisans. Local black attorney Homer G. Phillips led a campaign for a civic improvements bond issue that would provide for the construction of a larger hospital for blacks.

When the bond issue was passed in 1923, the city refused to allocate funding for the hospital, instead advocating a segregated addition to the original City Hospital, located in the Peabody-Darst-Webbe neighborhood and distant from the center of black population. Phillips again led the efforts to implement the original plan for a new hospital, successfully debating the St. Louis Board of Aldermen for allocation of funds to this purpose. Site acquisition resulted in the purchase of 6.3 acres in the Ville, the center of the black community of St. Louis. But, before construction could begin, Homer G. Phillips was shot and killed. Although two men were arrested and charged with the crime, they were acquitted; and Phillips’ murder remains unsolved.

Construction on the site began in October 1932, with the city initially using funds from the 1923 bond issue and later from the newly formed Public Works Administration. City architect Albert Osburg was the primary designer of the building, which was completed in phases. The central building was finished between 1933 and 1935, while the two wings were finished between 1936 and 1937. The hospital was dedicated on February 22, 1937, with a parade and speeches by Missouri Governor Lloyd C. Stark, St. Louis Mayor Bernard Francis Dickmann, and Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes. Speaking to the black community of St. Louis, Ickes noted that the hospital would help the community “achieve your rightful place in our economic system.” It was renamed in 1942 from City Hospital #2 to Homer G. Phillips, in his honor. (Wikipedia)

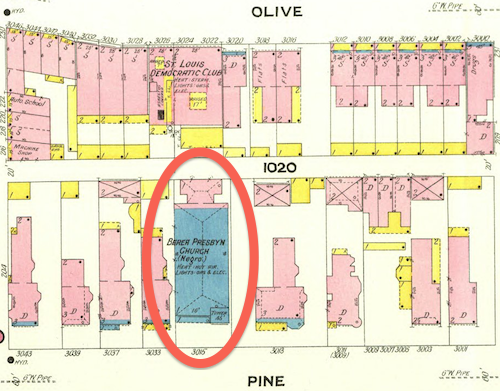

Prior to Homer G. Philips Hospital in the Ville, an existing building was used as City Hospital #2 between 1919-1936. That 19th century building was at Garrison & Lawton. That intersection no longer exists. Lawton was an east-west street between Pine and Laclede, known as Chestnut east of Jefferson. So yes, the first hospital for blacks in St. Louis was within the boundaries of the Mill Creek redevelopment area, for 17 years. Then the significantly larger City Hospital #2 opened in the Ville — where the wealthier black families lived.

As stated at the beginning, black residents lived in small pockets throughout the city. Wealth, social class, and geography separated the residents of the Ville from those in the older Mill Creek redevelopment area.

This is not to say every black person living in The Ville was wealthy, that was not the case. As poor blacks moved north to escape the Jim Crow south they likely lived where they could, including in The Ville. I know of one family that lived in The Ville during the 1940 census that had migrated from Alabama. I’d love to see maps showing where black persons lived in the region following the Civil War, showing shifts each decade. The change from 1950 to 1960 would give us better information on where families displaced by the demolition of Mill Creek relocated.

We know white home owners in the areas immediately outside The Ville had racially restrictive covenants on their properties since the early years of the 20th century. One block, now part of the Greater Ville neighborhood, was still white when the Shelley family had a white person act as the buyer so they could purchase 4600 Labdie in 1945. In 1948 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the court system couldn’t be used to enforce restrictive covenants (Shelley v Kraemer).

This prompted many white homeowners surrounding The Ville to sell and move further away. At the same time people were being forced to leave the Mill Creek Valley redevelopment area many more options were available on the city’s north side. Yes, some may have moved into numerous high-rise public housing projects that were open prior to the February 16, 1959 start of demolition in Mill Creek.

- Cochran Garden Apts, April 1953

- Pruitt-Igoe, 1955

- (In December 1955) a judge ruled St. Louis and the housing authority had to stop segregation in public housing.

- Vaughn Apts, October 1957

The low-rise Neighborhood Gardens and Carr Square Village opened in May 1935 and August 1942, respectively. Again, segregated until 1956. One of the problems with large-scale demolition is people get scattered in the process.

The demolition was certainly a land grab, no question. Wealthy whites living west in the Central West End, Clayton, Ladue, etc had to drive on Market Street to reach Union Station and the CBD. They didn’t like driving through old dense areas, especially predominantly occupied by African-Americans.

Back east demolition was increasingly happening. Soldiers Memorial opened in 1938, Aloe Plaza opened two years later — both on the north side of Market Street. St. Louis leaders got hooked on demolition so clearing out the west entry to downtown followed. Also in the late 1930s the Oakland Express opened, a highway from Skinker to Vandeventer & Chouteau.

Hopefully the incorrect information will cease.

— Steve Patterson