Rapid Urbanization of Dardenne Creek Watershed in St. Charles County Has Dramatically Increased Runoff

Record rainfall has resulted in flooding in the region, notably St. Charles County. On Sunday a major interstate highway was closed in both directions:

Both directions of Interstate 70 remain closed in St Charles County near Route 79 in St Peters due to rising flood waters from the Dardenne Creek. The eastbound lanes closed around noon Sunday, December 27 and the westbound lanes closed around 2:30 p.m.

It is expected that both the eastbound and westbound lanes will remain closed for Monday morning rush hour traffic.

Motorists who need to use eastbound I-70 in St Charles County can exit at Interstate 64 eastbound to Route 364 eastbound. Route 364 connects to Interstate 270 in St. Louis County and from there motorists can reconnect to Interstate 70. Westbound I-70 travelers will have to exit the highway at Route 94 in St Charles. They can take westbound Route 94 to westbound I-64 to connect back to I-70. (MoDOT)

The Dardenne Creek watershed flooded onto the interstate:

A watershed is an area of land where the runoff from rain or snow will ultimately drain to a particular stream, river, wetland or other body of water. There are nine major watersheds in the St. Louis region which drain into the Mississippi River and the Missouri River. Nested within these watersheds can be found smaller watersheds of creeks or streams and those segments of land which drain directly into the nine major watersheds. The following sections delineate the watersheds in the St. Louis region, discuss watersheds and watershed based natural resource planning and describe the actions the general public and local governments can take to improve water quality in their watersheds. (East-West Gateway Council of Governments)

While the record rainfall is big factor in the flooding, we can’t continue to ignore the role of urbanization plays. The better term, however, is suburbanization. Low density development with lots of rooftops, parking lots, and wide roads to connect it all. Coupled with dramatic population growth, too much of the county is paved over.

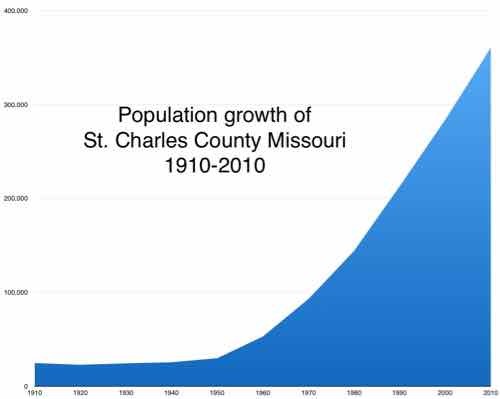

Here is the population of St. Charles County, per decade, with the percentage of growth from the previous.

- 1910 24,695 0.9%

- 1920 22,828 ?7.6%

- 1930 24,354 6.7%

- 1940 25,562 5.0%

- 1950 29,834 16.7%

- 1960 52,970 77.5%

- 1970 92,954 75.5%

- 1980 144,107 55.0%

- 1990 212,907 47.7%

- 2000 283,883 33.3%

- 2010 360,485 27.0%

Below is the visual:

Flooding is an unintended consequence of this growth — all those parking lots add up! Had they planned development to be more compact and respectful of the watershed the current flooding wouldn’t be as extreme. Two geography students looked at this in a paper published in 2009: IMPACTS OF URBANIZATION ON SURFACE RUNOFF OF THE DARDENNE CREEK WATERSHED, ST. CHARLES COUNTY, MISSOURI.

Some quotes:

Urbanization, a common land use/land cover (LULC) change in suburban areas, has become a significant environmental concern in the United States. Urban areas are continuously increasing at an alarming rate (22.7 ha per hour in 1982–1997) as reported by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (USEPA, 2009). Although it provides enormous social and economic benefits, urbanization creates a significant amount of impervious surface by converting vast area of croplands, for- ests, grasslands, and wetlands into urban uses. The conversion alters natural hydro- logic processes and results in profound environmental consequences within a watershed, such as increasing the volume and rate of surface runoff and reducing ground water recharge (Carter, 1961; Andersen, 1970; Lazaro, 1990; Moscrip and Montgomery, 1997; Tang et al., 2005). Expanded impervious cover also reduces runoff lag time and increases the peak discharge of stream flow, resulting in larger and more frequent incidents of flooding (Field et al., 1982; Hall, 1984) and subse- quent increases in the scouring and incision of streams (Leopold, 1973; Booth, 1990; Doyle et al., 2000). Furthermore, the increase of impervious surface area degrades water quality of the stream, which is a major transporter and concentrator of pollutants (such as nutrients, heavy metals, and pesticides) in runoff and sedi- ments (Schueler, 1995). Percent impervious surface area in a watershed has been used as an important indicator of the ecological and environmental conditions of an aquatic system (Schueler, 1995; Arnold and Gibbons, 1996).

The Dardenne Creek watershed in St. Charles County, a suburb of St. Louis, Missouri, has experienced significant urban expansion in past decades. Events such as road overtopping in 2005 as a result of the highest flood level recorded since stream gages were installed in 1999 (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 2007) have focused public attention on the need to understand how the pattern and magnitude of past LULC change have impacted runoff, and how future development and miti- gation might change watershed hydrology. The aim of the work reported here was to provide a quantitative assessment of the impact of past urbanization on surface runoff, and a baseline calibrated model for future efforts to assess potential hydro- logical impacts of new urban development and LULC change.

In the lower portion of the watershed, both forests and agricultural lands decreased from 1982 to 2003, although the rate of decrease became lower after 1987. Corresponding to the decrease of these two LULC classes, urbanization was apparent between 1982 and 2003. In 1982, urban areas only covered 7.4% of the area. After that, they increased at approximately 2.1% per year and became one of the dominant classes in 2003 (50.5%) (Figs. 3B and 3D). LULC change in the upper portion of the watershed was less dramatic (Figs. 3C and 3D) because of its remote location from the metropolitan area. Forest cover in the upper portion was higher than in the lower portion. Forest cover decreased 11.2% from 1982 to 1987 and tended to be stable in the following years. Different from the lower portion, agricultural lands increased from 1982 to 1991, a possible correspondence of deforestation. Agricultural lands decreased after 1991 at a much lower rate than that in the lower portion. Urbanization in the upper portion was limited. Urban areas were only 0.4% in 1982 and gradually increased to 10.9% in 2003.

Results indicated that the watershed experienced rapid urbanization from 1982 to 2003. Urban areas increased from 3.4% in 1982 to 27.3% in 2003 in the whole watershed. Urbanization dominated in the lower portion of the watershed and gradually migrated to the upper watershed due to the proximity to the metropolitan area of the city of St. Louis. As a direct result of the urbanization from 1982 to 2003, the long-term surface runoff increased >70% for the whole watershed (>95% and >48% in the lower and upper portion of the watershed, respectively). The runoff increase was highly correlated with the percentage of urban areas (R2 > 0.90). Cou- pled with significant flooding events in 1993 and 2005, this work helps raise aware- ness of the actual scale of hydrologic impacts of urbanization in this particular watershed, and provides a simple calibrated tool for local planners to use in assess- ing potential impacts of future development and mitigation activities. More generally, such case studies provide important insight both into the scale of impact of complex land-use change and into approaches that can be used to evaluate, plan, and manage watersheds.

So what can be done about it now, isn’t it too late? No!

I’ve talked about Retrofitting Suburbia before. Architect Ellen Dunham-Jones suggests, in her TED talk, we can daylight creeks, rebuild wetlands, etc. The solution is to literally urbanize some suburbanized areas, while returning others to rural, wetlands.

However, I seriously doubt the conservative electorate in St. Charles County is willing to do what is necessary. Flooding will likely continue.

— Steve Patterson