Recent Book — “Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It” by M. Nolan Gray

Over a century ago a new idea called “zoning” began, intended to guide cities to grow in a less chaotic manner than they had until then. Reality, however, was very different. It’s time to let go, change.

A recently published book explains the why & how.

What if scrapping one flawed policy could bring US cities closer to addressing debilitating housing shortages, stunted growth and innovation, persistent racial and economic segregation, and car-dependent development?

It’s time for America to move beyond zoning, argues city planner M. Nolan Gray in Arbitrary Lines: How Zoning Broke the American City and How to Fix It. With lively explanations and stories, Gray shows why zoning abolition is a necessary—if not sufficient—condition for building more affordable, vibrant, equitable, and sustainable cities.

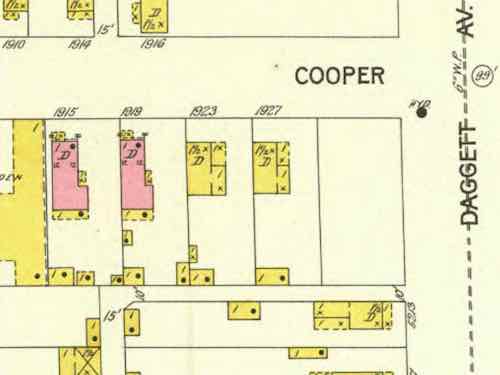

The arbitrary lines of zoning maps across the country have come to dictate where Americans may live and work, forcing cities into a pattern of growth that is segregated and sprawling.

The good news is that it doesn’t have to be this way. Reform is in the air, with cities and states across the country critically reevaluating zoning. In cities as diverse as Minneapolis, Fayetteville, and Hartford, the key pillars of zoning are under fire, with apartment bans being scrapped, minimum lot sizes dropping, and off-street parking requirements disappearing altogether. Some American cities—including Houston, America’s fourth-largest city—already make land-use planning work without zoning.

In Arbitrary Lines, Gray lays the groundwork for this ambitious cause by clearing up common confusions and myths about how American cities regulate growth and examining the major contemporary critiques of zoning. Gray sets out some of the efforts currently underway to reform zoning and charts how land-use regulation might work in the post-zoning American city.

Despite mounting interest, no single book has pulled these threads together for a popular audience. In Arbitrary Lines, Gray fills this gap by showing how zoning has failed to address even our most basic concerns about urban growth over the past century, and how we can think about a new way of planning a more affordable, prosperous, equitable, and sustainable American city. (Island Press)

St. Louis’ first city planner, Harland Bartholomew, a civil engineer, was big on zoning. His planning firm unfortunately helped hundreds of municipalities adopt zoning laws — including in St. Louis. This form of zoning is known now as used-based zoning based on how it separates everything into separate pods. No longer can a business owner build a new building with their apartment over their store — these uses must be separate. No longer can a 2-family residential building be near single-family detached houses — these must be separate.

The latter ended up being a way of keeping immigrant/people of color communities separated from white folks — because whites shouldn’t be subjected to living near anyone different than themselves. Idyllic new suburbs, in their mind, meant all white — except for servants, of course. This attitude wasn’t limited to just the Jim Crow south, northern cities joined in this more subtle form of housing discrimination.

The St. Louis region is a prime example — it’s one reason why we have so many tiny municipalities. Going forward we must change the status quo, otherwise the entire region will continue to suffer.

Gray’s book will help you understand the problems & solutions.

— Steve Patterson