It Is Time For Marijuana Legalization

Growing up when & wear I did, 70s/80s Oklahoma, I bought into the government’s War on Drugs:

First Lady Nancy Reagan became the public face of “Just Say No” after she made a trip to a New York ad agency in October 1983. She watched a demonstration of an anti-drug campaign from the Ad Council, the major charity of the advertising industry. Parents were told to “(g)et involved with drugs before your children do.” And school children were told that drug use and academic success don’t mix. As one print ad, with the title “School Daze,” put it: “School is tough enough without having to try to learn through a mind softened by drugs. So get the education you deserve. And learn how to say no to drugs.” According to The New York Times, Nancy Reagan approved: “Both of these themes are exactly right.” (The Atlantic)

Months before Nancy Reagan began the “Just Say No” campaign I turned 16. My mom didn’t want me to drink & drive — she’d let me drink at home, but I wasn’t interested. She told me about her trying a joint with co-workers years earlier — without any stigma. Again, I wasn’t interested. I think she knew to not to give me any reason to rebel. I was never offered marijuana in high school, though I’ve since learned it was readily available. In college I was offered a few times, my friends gave me a hard time for refusing to partake. I didn’t care.

This coming November marks 10 years since I tried marijuana the first time, I was 38 (see There Is A First Time For Everything). That day remains the only time I’ve “smoked” marijuana. It was nearly seven years later before I tried it a second time — by vaping — not smoking. Since then I’ve vaped a few more times, and ate way too much of a brownie in Colorado on our honeymoon last fall. What I have done is lots of reading on our national drug policy for the last 75+ years.

Here’s a timeline on the origins of our ban on marijuana, from PBS’ Frontline:

1900 – 20s Mexican immigrants introduce recreational use of marijuana leaf

After the Mexican Revolution of 1910, Mexican immigrants flooded into the U.S., introducing to American culture the recreational use of marijuana. The drug became associated with the immigrants, and the fear and prejudice about the Spanish-speaking newcomers became associated with marijuana. Anti-drug campaigners warned against the encroaching “Marijuana Menace,” and terrible crimes were attributed to marijuana and the Mexicans who used it.

1930s Fear of marijuana

During the Great Depression, massive unemployment increased public resentment and fear of Mexican immigrants, escalating public and governmental concern about the problem of marijuana. This instigated a flurry of research which linked the use of marijuana with violence, crime and other socially deviant behaviors, primarily committed by “racially inferior” or underclass communities. By 1931, 29 states had outlawed marijuana.

1930 Creation of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN)Harry J. Anslinger was the first Commissioner of the FBN and remained in that post until 1962.

1932 Uniform State Narcotic ActConcern about the rising use of marijuana and research linking its use with crime and other social problems created pressure on the federal government to take action. Rather than promoting federal legislation, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics strongly encouraged state governments to accept responsibility for control of the problem by adopting the Uniform State Narcotic Act.

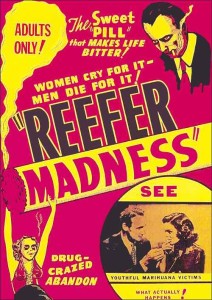

1936 “Reefer Madness”

Propaganda film “Reefer Madness” was produced by the French director, Louis Gasnier.

The Motion Pictures Association of America, composed of the major Hollywood studios, banned the showing of any narcotics in films.

1937 Marijuana Tax Act

After a lurid national propaganda campaign against the “evil weed,” Congress passed the Marijuana Tax Act. The statute effectively criminalized marijuana, restricting possession of the drug to individuals who paid an excise tax for certain authorized medical and industrial uses.

Remember that national prohibition on alcohol took place from 1920-1933. With the 1933 repeal of the 18th Amendment the morality crusaders turned to marijuana. Here’s the trailer for the 1936 propaganda film “Reefer Madness”

The full film (1:08) is on YouTube, click here to watch.

Less than three decades later the ban began to fall apart:

In 1966 the New York County Medical Society officially classified marijuana as a mild hallucinogen, insisting that there was no credible evidence proving its use to be associated with crimes of violence in the United States. In 1967 President Johnson’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of justice questioned the entire impact of the Marijuana Tax Act:

The Act raises an insignificant amount of revenue and exposes an insignificant number of marijuana transactions to public view, since only a handful of people are registered under the Act. It has become, in effect, solely- a criminal law, imposing sanctions upon persons who sell, acquire, or possess marijuana. . . . Marijuana is equated in law with the opiates, but the abuse characteristics of the two have almost nothing in common. The opiate produces physical dependence. Marijuana does not. A withdrawal sickness appears when use of the opiates is discontinued. No such symptoms are associated with marijuana. The desired dose of opiates tends to increase over time, but this is not true of marijuana. Both can lead to psychic dependence, but so can almost any substance that alters the state of consciousness. (Source)

In 1969 the US Supreme Court, in a unanimous decision, ruled the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937 unconstitutional, see Leary v United States. Congress and the new Nixon Administration acted quickly:

The Controlled Substances Act (CSA) was passed by the 91st United States Congress as Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 and signed into law by President Richard Nixon. The CSA is the federal U.S. drug policy under which the manufacture, importation, possession, use and distribution of certain substances is regulated. The Act also served as the national implementing legislation for the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.

The legislation created five Schedules (classifications), with varying qualifications for a substance to be included in each. Two federal agencies, the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Food and Drug Administration, determine which substances are added to or removed from the various schedules, though the statute passed by Congress created the initial listing, and Congress has sometimes scheduled other substances through legislation such as the Hillory J. Farias and Samantha Reid Date-Rape Prevention Act of 2000, which placed gamma hydroxybutyrate in Schedule I. Classification decisions are required to be made on criteria including potential for abuse (an undefined term), currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and international treaties. (Wikipedia)

From the DEA:

Schedule I drugs, substances, or chemicals are defined as drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. Schedule I drugs are the most dangerous drugs of all the drug schedules with potentially severe psychological or physical dependence. Some examples of Schedule I drugs are:

heroin, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), marijuana (cannabis), 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy), methaqualone, and peyote

Marijuana is viewed by the federal government to be the same as heroin, LSD, & ecstasy. Not everyone agrees. In 2009 CNN’s Dr. Sanjay Gupta opposed medical marijuana. Four years later he famously changed his view after working on a special report called Weed:

I apologize because I didn’t look hard enough, until now. I didn’t look far enough. I didn’t review papers from smaller labs in other countries doing some remarkable research, and I was too dismissive of the loud chorus of legitimate patients whose symptoms improved on cannabis.

Instead, I lumped them with the high-visibility malingerers, just looking to get high. I mistakenly believed the Drug Enforcement Agency listed marijuana as a schedule 1 substance because of sound scientific proof. Surely, they must have quality reasoning as to why marijuana is in the category of the most dangerous drugs that have “no accepted medicinal use and a high potential for abuse.”

They didn’t have the science to support that claim, and I now know that when it comes to marijuana neither of those things are true. It doesn’t have a high potential for abuse, and there are very legitimate medical applications. In fact, sometimes marijuana is the only thing that works. Take the case of Charlotte Figi, who I met in Colorado. She started having seizures soon after birth. By age 3, she was having 300 a week, despite being on seven different medications. Medical marijuana has calmed her brain, limiting her seizures to 2 or 3 per month.

You can see Weed below — HIGHLY RECOMMENDED:

I also recommend the follow-up report Weed 2. Both look at the use of marijuana oil for treatment of epilepsy in young children. Many parents moved their families to Colorado to get low-THC/high-CBD strains like Charlotte’s Web for their children. Last year Missouri passed a bill to allow medical marijuana for these patients. In February we moved closer to making it available here:

This week, the Missouri Department of Agriculture issued two licenses for hemp cultivation and production. These are the first such licenses issued since lawmakers passed a bill last year, permitting patients suffering from seizures to use hemp oil for treatment.

The two recipients are non-profit organizations based in the St. Louis area: Noah’s Arc Foundation, listed with a Chesterfield address, and BeLEAF Corporation, to be located on a piece of land in St. Peters.

Hemp oil is extracted from cannabis, and the kind used for treating seizures will not have enough of the psychoactive chemical -THC – to cause a high. (KSDK)

The bill unanimously passed the Missouri Senate in May last year after a colleague made a personal plea:

Sen. Eric Schmitt, R-Glendale, told a hushed chamber that his son had his first infantile spasm at 11 months old and a four-hour seizure when he was 2 years old. (Post-Dispatch)

I don’t doubt that without a member of the Missouri legislature being personally affected we wouldn’t be at this point. But what about people seeking medical marijuana for:

- Muscle spasms caused by multiple sclerosis

- Nausea from cancer chemotherapy

- Poor appetite and weight loss caused by chronic illness, such as HIV, or nerve pain

- Seizure disorders

- Crohn’s disease (source:WebMD)

We might have to wait until more legislators are affected by any of the above, or we may take action at the ballot box:

Americans of all political stripes say the federal government should not interfere with state-level legalization efforts: 58 percent of Democrats, 54 percent of Republicans, and 64 percent of Independents agree on this. Even 38 percent of people who oppose legalization still say that the federal government should not enforce federal pot laws in states that have legalized.

The Obama administration has generally followed this hands-off approach and given states the space to carry out their legalization experiments. But just yesterday, New Jersey Governor and potential 2016 candidate Chris Christie said that he would discontinue this practice and “crack down and not permit” legalization at the state level if he become president. (Washington Post: How marijuana legalizers are winning the battle for hearts and minds)

I think medical & recreational marijuana will be issues in the 2016 elections, at both state and national levels.

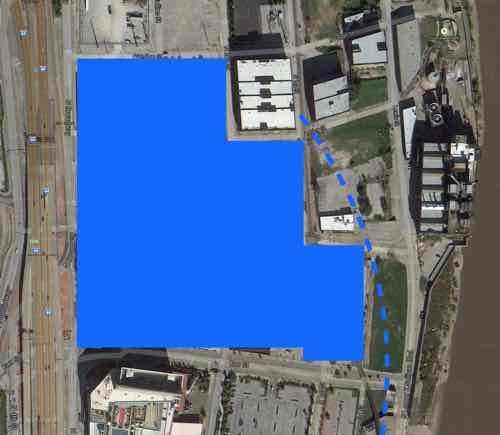

In Missouri, organizations like Show-Me Cannabis are working hard to legalize medical marijuana. They’ve put up billboards, bought radio spots, and recently brought one hundred supporters to Jefferson City to lobby legislators, many whom expressed optimism about the prospects for industrial hemp and medical cannabis this session.

One vocal cannabis advocate in St. Louis is Steve Patterson, a man the Riverfront Times calls “one of the city’s influential voices on urban planning and public policy” for his award winning blog Urban Review STL. A child of Nancy Regan’s “Just Say No” campaign, Patterson was opposed to drugs until he first tried pot at age 38. Since then he’s enjoyed vaping it, and has pondered the history of cannabis prohibition and the failed War on Drugs.

“The reasons why cannabis was made illegal in the thirties and listed as a Schedule I drug in 1970 have no basis in fact. Schedule I drugs are considered highly addictive with no medicinal value. Cannabis has always had medicinal uses” Patterson says, before pointing out that alcohol and tobacco are far more addictive and deadly. “There are 2.5 million alcohol related deaths annually, but nobody has ever overdosed on cannabis.” (The Vital Voice: The Politics of Pot)

The Post-Dispatch has already endorsed legalization:

Legalizing marijuana is not some panacea. It comes with all sorts of other problems, such as potential for increased abuse, conflict with federal law and border states that have different laws, and many of the same issues that are dealt with regularly with abuse of alcohol.

But the nation is quickly changing its views on legalized marijuana, and Missouri should thrust itself to the forefront of the debate, primarily because of its location in the center of the country and its reliance on agriculture and life sciences as major economic drivers.

See Show-Me Cannabis for more information. Naturally, makers of legal drugs (pharmaceutical, tobacco, alcohol) are generally opposed to legalization of marijuana — but all three have a poor record with addiction and death.

Besides state level legalization, marijuana needs to be removed as a Schedule 1 drug — it’s past time to move beyond 1930s hysteria! It’s time to move beyond mandatory sentencing & mass incarceration.

— Steve Patterson