A St. Louis Statue to be Proud of: Frankie Freeman in Kiener Plaza

|

|

Recently there have been renewed calls for the removal of statues honoring confederates. Just yesterday:

On Wednesday, the House took a pivotal first step in an overwhelming vote to remove a bust of the fifth chief justice of the United States and Confederate statues from public display in the U.S. Capitol.

The final vote was 305-113. There were 72 Republicans who joined with Democrats in approving the measure. (ABC News)

Another target has been homicidal tyrant Christopher Columbus. Last month the St. Louis statue honoring him was removed.

A statue of Christopher Columbus that stood in a St. Louis park for 134 years was removed Tuesday amid a growing national outcry against monuments to the 15th century explorer.

The commissioners who oversee Tower Grove Park recently voted to remove the statue. It was loaded onto a truck Tuesday, but it wasn’t clear what will become of it. Park officials didn’t immediately reply to a phone message seeking comment. (AP/MSN)

The controversial statue of King Louis IX remains on Art Hill, for now.

Installed in 1906, the Apotheosis of St. Louis depicts the city’s namesake, Louis IX of France, riding astride an armored horse, his sword raised upside down to form a cross. It’s a portrayal befitting a ruler renowned for his military prowess. But the statue fails to address the canonized king’s darker legacy—the totality of his accomplishments—and now, amid a spate of protests against systemic racism in the United States, the St. Louis monument is one of many public works at the center of a major cultural reckoning. (Smithsonian Magazine)

Amid all this controversy I wanted to think about positive role models honored in bronze. The Martin Luther King Jr. statue in Fountain Park came to mind first. Then my mind turned to one of the newest statues in St. Louis, installed in November 2017:

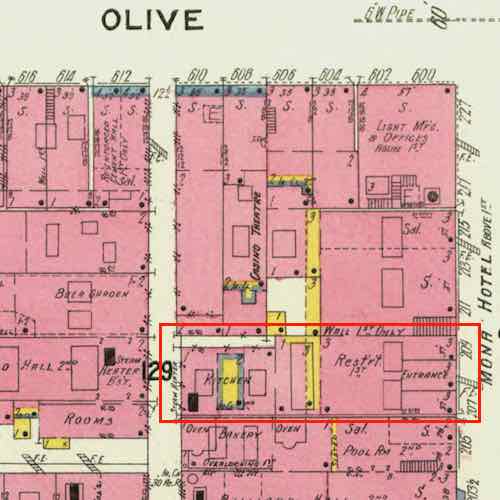

The bronze figure depicts Freeman walking away from the Old Courthouse. It’s symbolic of her leaving after the 1954 landmark case “Davis et. al. v. the St. Louis Housing Authority,” which resulted in the end of legal racial discrimination in St. Louis public housing. Freeman was the lead attorney for the case.

A few days before her 101st birthday, Freeman sat next to the statue on Tuesday and greeted visitors who came to celebrate her, from U.S. Sen. Claire McCaskill to former Washington University Chancellor Dr. William Danforth. (Post-Dispatch)

Freeman died the following January. Why does she have a statue in Kiener Plaza?

Freeman, also known as “Frankie Freedom,” was raised in a segregated town in Virginia. She knew she wanted to become a lawyer since she was young. Eventually, she became a civil rights attorney who fought to end segregated housing and promoted equal rights in St. Louis and nationwide during the civil rights movement.

She was also the lead attorney in the court case Davis v. St. Louis Housing Authority in 1952, which helped in ending racial segregation in public housing in St. Louis. “Frankie Freedom” became an assistant attorney general of Missouri and staff attorney for the St. Louis Land Clearance and Housing Authorities from 1956 to 1970.

Freeman became the first woman to join the U.S Civil Rights Commission in 1964, which investigates discrimination complaints, collects data on discrimination, and advises lawmakers and the president on equal protection and the issues of discrimination. She served on the commission for 16 years.

She was also an active member and longtime board member of the United Way and was part of the leadership of the Girl Scouts. (Newsweek)

Freeman spent her entire life working toward equality for all — we should be proud she made St. Louis her home.

Further reading see Davis et al. v. The St. Louis Housing Authority at Wikipedia and/or JUSTIA. Watch her on YouTube via Missouri Historical Society.

— Steve Patterson