Not All African-American’s Worship(ed) a Deity

|

|

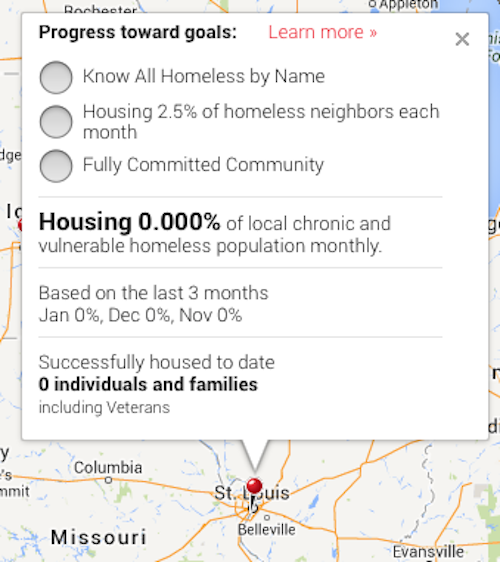

I couldn’t let February go by without one post on Black History. I know you’re thinking, “what can a white guy have to add to a dialog about black history?” Well, I can address one aspect of black history that’s often either ignored or deliberately hidden: African-American atheists/agnostics. They don’t fit the accepted narrative of African-Americans as all religious. Still, the nonreligious is a small percentage:

Slightly more than one-in-ten African-Americans (12%) report being unaffiliated with any particular religion. Although the unaffiliated make up a smaller proportion of the African-American community (12%) than of the adult population overall (16%), the unaffiliated still constitute the third largest “religious” tradition within the black community. However, very few African-Americans (1%) describe themselves as atheist or agnostic. Instead, most unaffiliated African-Americans (11% of African-Americans overall) simply describe their religion as “nothing in particular.” Indeed, among the African-American unaffiliated population, a significant majority (72%) says religion is at least somewhat important in their lives. (A Religious Portrait of African-Americans — recommended)

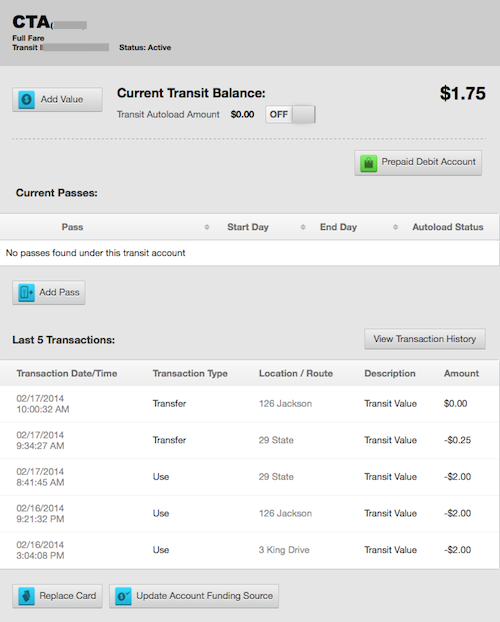

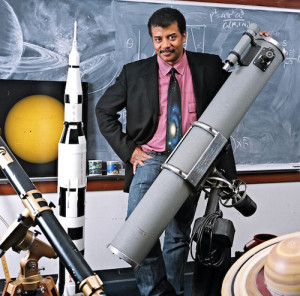

One of the current top freethinkers is the brilliant astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of the Hayden Planetarium:

Tyson is the recipient of eighteen honorary doctorates and the NASA Distinguished Public Service Medal, the highest award given by NASA to a non-government citizen. His contributions to the public appreciation of the cosmos have been recognized by the International Astronomical Union in their official naming of asteroid 13123 Tyson. On the lighter side, Tyson was voted Sexiest Astrophysicist Alive by People Magazine in 2000.

In February 2012, Tyson released his tenth book, containing every thought he has ever had on the past, present, and future of space exploration: Space Chronicles: Facing the Ultimate Frontier. Currently, Tyson is working on a 21st century reboot of Carl Sagan’s landmark television series COSMOS, to air in 13 episodes on the FOX network in the spring of 2014. (bio)

He’s one of the leading defenders of science, working to keep creationism out of science classrooms, here’s a few quotes:

I don’t have an issue with what you do in the church, but I’m going to be up in your face if you’re going to knock on my science classroom and tell me they’ve got to teach what you’re teaching in your Sunday school. Because that’s when we’re going to fight.

Whenever people have used religious documents to make accurate predictions about our base knowledge of the physical world, they have been famously wrong.

Once upon a time, people identified the god Neptune as the source of storms at sea. Today we call these storms hurricanes…. The only people who still call hurricanes acts of God are the people who write insurance forms.

If all that you see, do, measure and discover is the will of a deity, then ideas can never be proven wrong, you have no predictive power, and you are at a loss to understand the principles behind most of the fundamental interconnections of nature.

There’s no tradition of scientists knocking down the Sunday school door, telling the preacher, That might not necessarily be true. That’s never happened. There’re no scientists picketing outside of churches.

Neil deGrasse Tyson is a popular celebrity, appearing on shows like Moyers & Company and The Daily Show, for example. Yes, a scientist as a celebrity!

In 2012 USA Today did a story on some 20th Century African-Americans who rejected a deity, here’s their list:

James Baldwin (1924-1987), poet, playwright, civil rights activist

Once a Pentecostal preacher, Baldwin’s 1963 book, The Fire Next Time, describes how “being in the pulpit was like being in the theatre; I was behind the scenes and knew how the illusion worked.” Baldwin never publicly declared his atheism, but he was critical of religion. “If the concept of God has any validity or any use,” he wrote, “it can only be to make us larger, freer, and more loving. If God cannot do this, then it is time we got rid of him.”

W.E.B DuBois (1868-1963), co-founder of the NAACP

Columbia University professor Manning Marable wrote that DuBois’ 1903 work, The Souls of Black Folk, “helped to create the intellectual argument for the black freedom struggle in the 20th century.” DuBois described himself as a freethinker and was sometimes critical of the black church, which he said was too slow in supporting or promoting racial equality.

Lorraine Hansberry (1930-1965), playwright and journalist

Hansberry’s partly autobiographical play A Raisin in the Sun, shocked Broadway audiences when a black character declared, “God is just one idea I don’t accept. … It’s just that I get so tired of him getting credit for all the things the human race achieves through its own stubborn effort. There simply is no God! There is only man, and it’s he who makes miracles!” She worked with W.E.B. DuBois and Paul Robeson on an African-American progressive newspaper, but her life was cut short at age 34 by cancer.

Hubert Henry Harrison (1883-1927), activist, educator, writer

Harrison promoted positive racial consciousness among African-Americans and is credited with influencing A. Philip Randolph and the godfather of black nationalism, Marcus Garvey. Harrison proudly declared his atheism and wrote, “Show me a population that is deeply religious and I will show you a servile population, content with whips and chains, … content to eat the bread of sorrow and drink the waters of affliction.”

A. Philip Randolph (1889-1979), labor organizer

Randolph was the founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first predominantly black union. He helped convince President Franklin Roosevelt to desegregate military production factories during World War II, and organized the 1963 March on Washington with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. In 1973, Randolph signed the Humanist Manifesto II, a public declaration of Humanist principles. He is reported to have said of prayer: “Our aim is to appeal to reason. … Prayer is not one of our remedies; it depends on what one is praying for. We consider prayer nothing more than a fervent wish; consequently the merit and worth of a prayer depend upon what the fervent wish is.”

Carter G. Woodson (1875-1950), journalist and historian

In 1926, Woodson proposed “Negro History Week,” which later evolved into Black History Month. In 1933, he wrote in The Mis-Education of the Negro that “the ritualistic churches into which these Negroes have gone do not touch the masses, and they show no promising future for racial development. Such institutions are controlled by those who offer the Negroes only limited opportunity and then sometimes on the condition that they be segregated in the court of the gentiles outside of the temple of Jehovah.”

Richard Wright (1908-1960), novelist and author

In his memoir Black Boy, Wright wrote, “Before I had been made to go to church, I had given God’s existence a sort of tacit assent, but after having seen his creatures serve him at first hand, I had had my doubts. My faith, as it was, was welded to the common realities of life, anchored in the sensations of my body and in what my mind could grasp, and nothing could ever shake this faith, and surely not my fear of an invisible power.” (USAToday — Blacks say atheists were unseen civil rights heroes)

Another is Langston Hughes

Hughes associated religious authority with other oppressive forces in contemporary America. As one of America’s forgotten black atheists, he was easily an expert on prejudice. (And if being black, allegedly communist, and atheist didn’t subject him to enough prejudice, there were always the rumors that he was gay.) (5 Famous Americans You Never Knew Were Atheists)

Today there’s organizations like African Americans for Humanism to alter the narrative:

African Americans may be the nation’s most religious minority, but the churches and religious leaders don’t speak for many of us.

Today as in the past, many African Americans question religion and religious institutions. More and more of us stand for reason over faith. Freethought over authority. Critical thinking in place of superstition. Many of us are nonreligious; some are nontheistic.

African Americans for Humanism supports skeptics, doubters, humanists, and atheists in the African American community, provides forums for communication and education, and facilitates coordinated action to achieve shared objectives.

The nearest chapter is Kansas City.

Hopefully this post provided a bit of history you weren’t aware of before.

— Steve Patterson