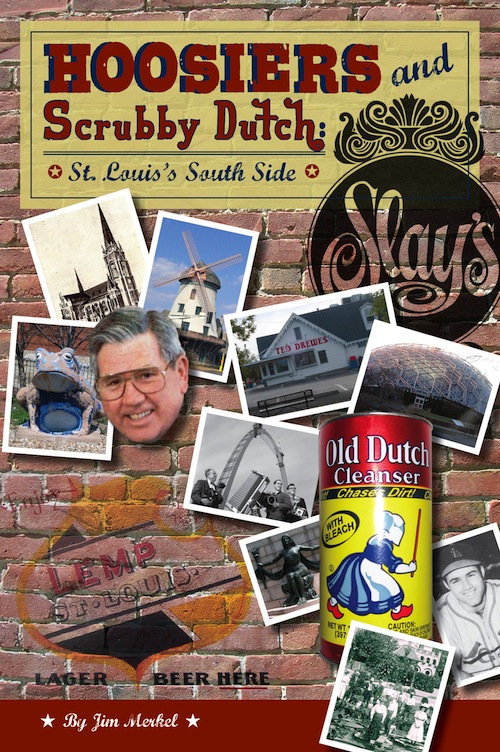

Hoosiers and Scrubby Dutch: St. Louis’s South Side

|

|

Hoosiers and Scrubby Dutch: St. Louis’s South Side is the title of a enthralling new book by Jim Merkel. Â The publisher’s description:

In St. Louis’s South Side, people stand in line for frozen treats named for building material, and women used to scrub their concrete steps every Friday. In the South Side, a stop sign means “tap the brakes quick,” and a restaurant masquerades as a windmill. In the South Side, a dentist once moonlighted as a murderer, and a bloody bank heist became the basis for an early Steve McQueen movie. And in the South Side, prepare to run if you use a particular local slur. Suburban Journals reporter Jim Merkel brings nearly ten years’ experience in covering the South Side. Herein are some of the people, places, and events that made the South Side a place like nowhere else. “South Siders are down-to-earth, good people,” this South Sider writes. “I’m staying until they drag me away for good.”

Merkel’s beat as a reporter for the Suburban Journals has been covering south St. Louis for years. This book enables him to share interesting stories about the people, places & events of the south side.

The following is one such story from page 70-71 of the book:

The Asylum on Arsenal Street

In August 1911, the area was shocked to learn how forty-year-old Eva Jarvoubek, a patient at the City Sanitarium, was choked to death by a straitjacket she was wearing. The outcry was loud about what happened at the city’s institution for the mentally ill. Dr. C. G. Chaddock, a member of the City Hospital Visiting Staff, told the State House Special Investigations Committee that the use of mechanical contrivances for quieting violent patients was wrong. Attendants too often used straitjackets and similar restraints when they should use humane care, he said. It was a brief moment of light for the institution inside a tall red brick domed building on a hill at 5400 Arsenal Street. After this incident, things went back to normal. The asylum once again became that looming building visible on the horizon throughout the South Side, where people wondered what went on inside. The asylum’s history was a mix of mistreatment and sincere efforts to help mentally ill people, always limited by a lack of funding. Instances of mistreatment have declined in recent years as effective medical treatments for mental illness have become known, but increasing limits in state funding have harmed efforts to improve the lives of mentally ill people at what is now known as the St. Louis Psychiatric Rehabilitation Center.

The institution first opened as the St. Louis County Lunatic Asylum on April 23, 1869. The building went up in the country, full of fresh air thought to help mental illness, said Barbara Anderson, who was volunteer director of the hospital from 1988 to 2006. The building itself was designed to bring that air inside. But in fact, treatment of any sort was wanting. “It was basically warehousing people with mental illnesses,” Anderson said. “There was no clinical criteria by which someone measured another as being psychologically disoriented,” she said. Sometimes women were brought in suffering from postpartum depression and often ended up institutionalized for years. “It was a way to get rid of your wife and run around with some young girl,” Anderson said. Patients also could have been alcoholics or suffering from syphilitic dementia, or just plain poor.

Treatment was cruel at worst and misguided at best. In the basement, some patients were placed in six-to-eight-foot-wide cubicles with straw on the floors. “People would defecate on the floor, and they would sweep it out every day,” Anderson said. “It was cold and damp down there, and people slept on the floors.” Those patients were usually African-American, or whites who were out of control. Upstairs, patients would be treated to all the amenities of the Victorian household, including reading rooms and pool rooms. These rooms also were thought to improve patients’ mental health. To shock them into sanity, people were placed in vats of ice cold water. “They did the best they could, based on the incredible ignorance they had,” Anderson said.

As time went on, the institution’s name changed to the St. Louis City Insane Asylum and then the City Sanitarium. When the city sold it to the state for one dollar in 1948, it became the St. Louis State Hospital. In 1997, it moved to new quarters on the same property at 5300 Arsenal Street and became the St. Louis Psychiatric Rehabilitation Center. The domed building at 5400 Arsenal became an office building for the Missouri Institute of Mental Health and the State Department of Mental Health.

Through the years, as the building’s name changed, one ineffective therapy replaced another. Patients danced, were given beauty treatments, and sang operettas. A newspaper ran a feature story about how straps, straitjackets, and manacles were replaced by outdoor recreation and occupational therapy, but other articles told of cramped and unsanitary conditions. Nothing really helped, though, until the discovery of medications that treated mental illness. However, here and elsewhere, their promise was limited when patients were released without enough of a structure to treat them in the community. Today, people continue to see the big building with the green dome on Arsenal Street wherever they go on the South Side. What they may not see is how budget cuts are still hurting patients.

This book is a must for any student of St. Louis history.

– Steve Patterson