Decisions Applicable To Bus Rapid Transit And Local Bus Service

Monday’s post Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) Not Right For St. Louis certainly ruffled a few feathers — at least among non-transit riding civic boosters. Lots of good discussion on the Facebook post. What we need next is to go through specifics one by one to see if there is any consensus. BRT has been implemented worldwide with great success. In general, BRT projects in the United States have been less robust than in other countries. That’s ok.

My previous post was simply saying we can’t have a gold-level bus rapid transit system, per the Institute for Transportation & Development Policy (ITDP) Scorecard. To date no BRT system in the USA has achieved a top gold rating. The ITDP has ranked 10 BRT lines in the US with the following results:

- Three (3) Basic

- Five (5) Bronze

- Two (2) Silver (Cleveland’s Healthline = 76, Hartford’s CTFasktrak Busway = 79.2)

- Zero (0) Gold

Countless others being marketed as BRT don’t even qualify for a “basic” designation. Ouch. I guess as long as the users are pleased with the line compared to a conventional local bus then it doesn’t really matter what it’s called. Interestingly none of the 10 in the US have BRT as part of their name. Our light rail system has two lines: Red & Blue.

Perhaps we come up with some criteria to use for calling a very high frequency bus route by a color name rather than the legacy bus number. For example, our busiest bus route (#70 Grand) could be the Green Line. Maybe if we made big changes to the #95 Kingshighway bus route it becomes the Orange Line? And so on. Then we wouldn’t need to quibble over the BRT term.

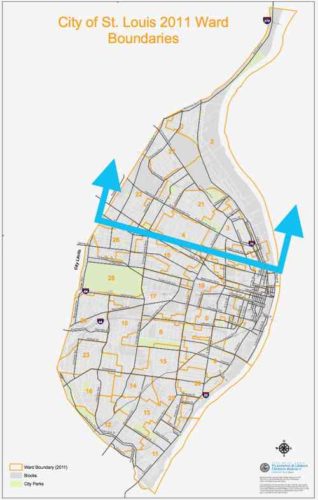

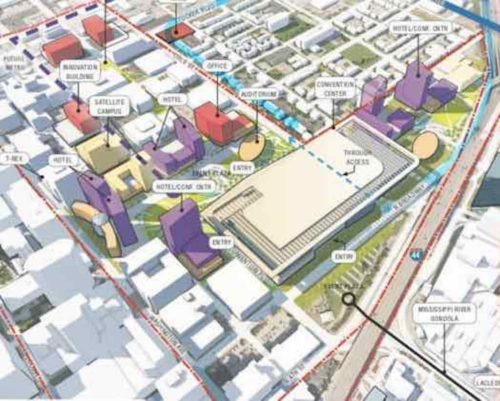

Where I think we can agree is our next big transit investment in the city will have rubber-tired transit vehicles, not rails. How St. Louis County invests their transit dollars is a separate issue, they might opt for light rail in a street and/or an extension south from the Shrewsbury station. Today’s post is focused on the city, though applicable if the county considers a BRT-esque bus project.

Beyond the marketing name & tires there are many other items to be considered:

- Type of propulsion (diesel, hybrid, compressed natural gas (CNG), fuel cell electric, battery electric, overhead cable electric (commonly known as a trolleybus)

- Fare collection (on-board, off-board, honor, no fares)

- Boarding (curb height or raised platforms for level boarding; front door only or all doors)

- Stop intervals (2 blocks, 1/4 mile, 1/2 mile, more; if more than 2 block local will a local bus also run the route less frequently to serve those unwilling/unable to walk to the farther stops)

- Stop locations: center of street, right lane, or a mix of both)

Let’s go through each, discussing pros and cons to consider when making decisions.

#1 Type of Propulsion

In 2022 I think we should invest only in transit vehicles with zero tailpipe emissions. That would eliminate diesel, hybrid and CNG. The three electric options each have their own pros & cons, infrastructure needs. Battery electric buses, like the 60 foot articulated buses on the 70 are presumably heavier than an electric trolleybus. Overhead wires vs increased wear & tear on streets and sourcing of rare earth metals. Battery electric buses (BEB) need to be quick charged during service, whereas the trolleybus doesn’t need to — but not everyone likes overhead wires. Some trolleybuses have small batteries to allow them to operate any from overhead wires. Hydrogen fuel cells are another option, not sure if one can go all day without refueling during the day. If so, is that feasible. Fuel cell buses are heavier than trolleybuses but presumably lighter than BEBs.

Metro has historically purchased buses from Gillig, but the new articulated battery electric buses used on Grand came from New Flyer. The latter offers more sizes and propulsion choices.

#2 Fare Collection

This is an important area because it determines how the stops are designed. First is getting our transit agency caught up on fare technology — assuming we’re going to continue collecting fares from users.

In August 2006 a Metro engineer explained the then-concept of smart fare cards to me.

That was in August 2006, at the opening of the most recent extension of the high-floor light rail. Metro’s Gateway Card finally appeared in spring 2018 — twelve years later. It has been almost four years now and nobody uses it. When I ride the bus or light rail I don’t see others tapping their cards. These cards are available for full fare & senior customers only — I think I’m still the only non-senior reduced-fare user with a Gateway Card.

Metro was working on a website login and app to go with the card, but it seems they’ve abandoned it in favor of a smartphone app to use for fare payment. Millions were spent changing bus fare boxes to allow cards to be tapped, and readers were placed at the entrances to the 38 MetroLink stations so security could see the green light as each person taps their card to enter. Huge investment of time & money for nothing. People do use the Transit app to buy digital tickets & passes.

I prefer having a reloadable card that calculates if my second tap qualifies as a transfer or new ride. I’ve seen systems that use both smart cards and apps. The goal for all is to not have fare payment holding up boarding, When I visit Chicago locals and the vast majority of visitors use their smart card — boarding is so much faster.

A faster bus route isn’t going to have the driver give those who paid more a daily transfer. Yes, currently every Metro bus in the region gets little pads of transfers to use for that date only. Massive waste of time & money that Metro continues. You’ll often see these as litter around bus stops, especially since most bus stops lack basics like a trash can.

Moving on…

Lets assume everyone has a smart card. By tapping it on a reader at MetroLink station entrances (off-board) or on the bus farebox (on-board) the appropriate fee is deducted from the card balance. If funds are insufficient it gives you a red light & buzzer instead of green.

Since opening in 1993 our light rail has had off-board honor system fare collection. In response to calls for turnstiles it’s going from an open platform to a closed system. If we’re going to build nice new bus stops for a rapid line we need to decide where the user taps their card. Currently bus riders using the smartphone app show the driver their valid ticket upon entering, but that wouldn’t work if boarding is allowed at all 3 doors (60 foot articulated).

Would bus stops for a new rapid bus route have the honor system for accessing the platform & bus? I can’t imagine that would go over well. If we want fare verification performed off-board that means turnstiles. The current smartphone app isn’t designed for use with turnstiles in mind.

#3 Boarding

Two questions here, both related to #2 above. Platforms level with the bus floor speeds up the boarding process for everyone, whereas curb-level boarding requires passengers to step up into the bus.

In the case of us disabled users (wheelchair, walker, etc) typically a ramp is unfolded to come down to curb level. The BRT scoring is better for smaller horizontal gaps between the platform and the bus floor:

Even corridors that have been designed to accommodate platform-level boarding could have gaps if the buses do not dock properly. A significant gap between the platform and the bus floor undermines the time-savings benefits of platform-level boarding and introduces a significant safety risk for passengers. Such gaps could occur for a variety of reasons, from poor basic design to poor driver training and technical opinion varies on the best way to minimize the gap. (ITDP)

Some buses designed for BRT use have a bridge that can pop out to close the gap, others the driver has to come set a lightweight bridge in place.

The other aspect of boarding is if everyone enters through the front door only, or all doors. If the decision is made to eliminate fares, have turnstiles to access the platform, or the honor system, then boarding can happen at all doors.

#4 Stop intervals

This is a big one. With my power wheelchair I can go miles without any issues — assuming curb cuts are in place, snow & ice are cleared, etc. But many are used to frequent bus stops, people who use walkers or a cane might struggle if their local bus stop no longer exists. They might already walk a good distance to reach the bus route. The solution in some cities is to have the BRT bus stop roughly every half mile while also operating a less frequent local bus. By having fewer stops you increase the possibility of having new development occur at these points, assuming zoning is sympathetic to requiring increased density at these spots. Fewer stops requires public & political buy-in to make it successful.

#5 Stop locations

Where the stop is located depends on where the bus operates. If it’s in the center of the right-of-way then obviously you’re going to have center platforms. Keep in mind some systems have a mix — some center, some right. Like our light rail vehicles, BRT vehicles usually have doors on both sides to accommodate different platform locations based on particular conditions. Having center dedicated lanes with center stations, even part of the length of the route, improves performance. If so you’ve got to make sure pedestrians crossing to/from the center are safe from motorists. The nice thing about center platforms is if you want to go the opposite direction from where you are, you only need to cross half the street to get to the stop.

Closing Thoughts

Even if the ITDP doesn’t consider a big transit investment BRT the only two groups that matter are the public and the feds — the ones determining if a project qualifies for matching funds. Other regions are ok with their BRT line not meeting ITDP’s minimum criteria to be considered. It’s up to all of us to participate, listen to others.

— Steve Patterson

*