Urban Renewal Officially Ended In 1974, Still Alive In St. Louis

|

|

The redevelopment process commonly known as Urban Renewal, in retrospect, was largely a failure:

After World War II, urban planners (then largely concerned with accommodating the increasing presence of automobiles) and social reformers (focused on providing adequate affordable housing) joined forces in what proved to be an awkward alliance. The major period of urban renovation in the United States began with Title I of the 1949 Housing Act: the Urban Renewal Program, which provided for wholesale demolition of slums and the construction of some eight-hundred thousand housing units throughout the nation. The program’s goals included eliminating substandard housing, constructing adequate housing, reducing de facto segregation, and revitalizing city economies. Participating local governments received federal subsidies totaling about $13 billion and were required to supply matching funds.

Sites were acquired through eminent domain, the right of the government to take over privately owned real estate for public purposes, in exchange for “just compensation.” After the land was cleared, local governments sold it to private real estate developers at below-market prices. Developers, however, had no incentives to supply housing for the poor. In return for the subsidy and certain tax abatements, they built commercial projects and housing for the upper-middle class. Title III of the Housing Act of 1954 promoted the building of civic centers, office buildings, and hotels on the cleared land. Land that remained vacant because it was too close for comfort to remaining slum areas often became municipal parking lots. (source)

Jane Jacobs’ 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities rebuked the ongoing land clearance policies advocated by supporters of urban renewal. By the late 1960s one of St. Louis’ most prominent urban renewal projects — Pruitt-Igoe — was a disaster. Before the 20th anniversary the first of 33 towers were imploded in 1972 — urban renewal was unofficially over.

In 1974 it was officially over:

The Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 emphasized rehabilitation, preservation, and gradual change rather than demolition and displacement. Under the Community Development Block Grant program, local agencies bear most of the responsibility for revitalizing decayed neighborhoods. Successful programs include urban homesteading, whereby properties seized by the city for unpaid taxes are given to new owners who promise to bring them “up to code” within a given period—either by “sweat equity” (doing the work themselves) or by employing contractors—in return for free title to the property. Under the Community Reinvestment Act, lenders make low-interest loans to help the neighborhood revitalization process. (same source as first quote)

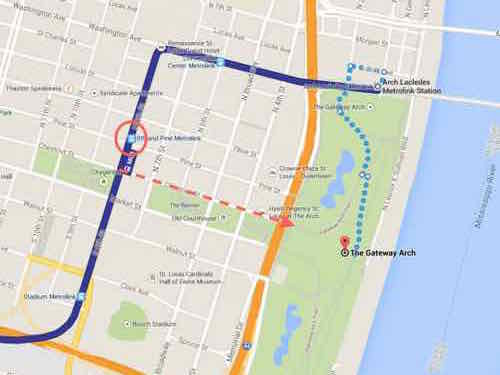

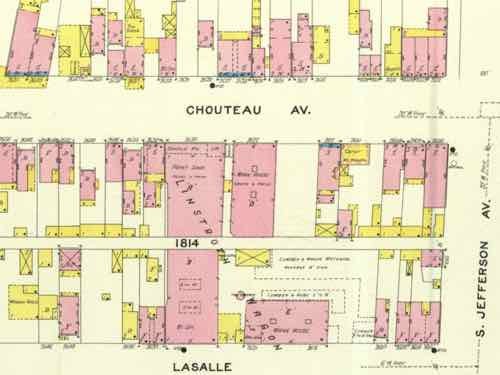

But forty plus years later the St. Louis leadership continues as if nothing changed. The old idea of marking off an area on a map to clear everything (homes, schools, businesses, churches, roads, sidewalks) within the red lined box remains as it did in the 1950s. The message from city hall is clear: don’t invest in North St. Louis because they can & will walk in and take it away.

What are the scenarios at this point?

A) National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency selects the city option:

- Businesses, residents, churches, etc are displaced.

- A 100-acre swath is purchased and cleared.

- The federal government builds a fortress-like campus, few workers would leave at lunch.

- No benefit to the surrounding neighborhoods, access to public transit cut off by monolithic campus.

- Adjacent areas now threatened as the next target for clearance, further eroding those areas.

- Fire Station Number 5 would remain, but because of the new campus, firefighters would be unable to quickly reach the area to the West of Jefferson/Parnell.

B) National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency selects another option:

- Nobody buys into this area because it’s now a known target area.

- It declines further because it’s a known target area.

- It’s taken later for some corporate campus.

C) An alternative if National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency selects another option:

- The city/community works with Paul McKee, existing businesses and property owners to develop a plan to revitalize the Cass & Jefferson/Parnell corridors and to coordinate with a new street grid in the long-vacsnt Pruitt-Ogoe site.

- The existing street grid is left fully intact.

- Infill planned with a variety of residential units with a concentration of retail & office at Cass & Jefferson.

But this won’t happen, St. Louis is forever stuck in the middle of the 20th century. Clearance for a new stadium and a QuikTrip are other current examples. It has been nearly 70 years since St. Louis adopted Harland Bartholomew’s City Plan and we’ve yet to stray from the thinking he outlined.

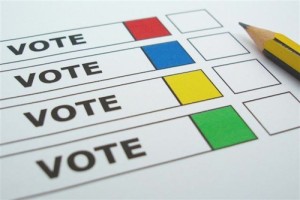

Here are the results from the Sunday Poll:

Q: Should the City of St. Louis use eminent domain powers to assemble a site if the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency selects the city option?

- No 20 [44.44%]

- Yes 14 [31.11%]

- Maybe 8 [17.78%]

- Unsure/No Opinion 3 [6.67%]

We shouldn’t be willing to raze 100 acres to retain earnings tax revenues. If there was hope the campus would help the surrounding area it might be a fair tradeoff, but it’ll further deteriorate and isolate. Still, this urban renewal mindset is so engrained I’m not sure we’ll ever break free of it.

Perhaps I should just give up?

— Steve Patterson